Method Article

Evaluation of Planar-Cell-Polarity Phenotypes in Ciliopathy Mouse Mutant Cochlea

W tym Artykule

Podsumowanie

Primary cilia influence various signaling pathways. The mammalian cochlea is ideal for examining planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling. Cilia dysfunction affects cochlear outgrowth, cellular patterning and hair cell orientation, readouts of PCP. Our goal is to analyze PCP signaling in mouse cochlea via phenotypic analysis, immunohistochemistry and scanning electron microscopy.

Streszczenie

In recent years, primary cilia have emerged as key regulators in development and disease by influencing numerous signaling pathways. One of the earliest signaling pathways shown to be associated with ciliary function was the non-canonical Wnt signaling pathway, also referred to as planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling. One of the best places in which to study the effects of planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling during vertebrate development is the mammalian cochlea. PCP signaling disruption in the mouse cochlea disrupts cochlear outgrowth, cellular patterning and hair cell orientation, all of which are affected by cilia dysfunction. The goal of this protocol is to describe the analysis of PCP signaling in the developing mammalian cochlea via phenotypic analysis, immunohistochemistry and scanning electron microscopy. Defects in convergence and extension are manifested as a shortening of the cochlear duct and/or changes in cellular patterning, which can be quantified following dissection from developing mouse mutants. Changes in stereociliary bundle orientation and kinocilia length or positioning can be observed and quantitated using either immunofluorescence or scanning electron microscopy (SEM). A deeper insight into the role of ciliary proteins in cellular signaling pathways and other biological phenomena is crucial for our understanding of cellular and developmental biology, as well as for the development of targeted treatment strategies.

Wprowadzenie

Primary cilia are long microtubule-based appendages that extend from the surface of most mammalian cells. Primary cilia are often confused with motile cilia, of which there are always multiple per cell, and whose purpose is to move fluid across membrane surfaces. Primary cilia, in contrast, adopt sensory roles and are consequently also referred to as sensory cilia. Once long forgotten, this organelle has recently been 'rediscovered' as a result of its association with a multitude of human genetic diseases1. Ideally positioned as a signaling organelle, the primary cilium has been shown to regulate numerous signaling pathways, many of which are important not only in tissue homeostasis and disease, but also during development2.

One of the first signaling pathways shown to be associated with cilia dysfunction was the non-canonical Wnt signaling pathway, known also as the planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway3. This signaling cascade initially identified in Drosophila, is critical for embryogenesis; in particular for convergence and extension processes and for the correct orientation of cells in the plane of epithelia4. The sequential signaling of a core set of regulatory proteins translates directional cues which ultimately lead to cytoskeletal rearrangements and result in the coordinated polarization of epithelial cells in a plane5. The process of convergence and extension is absolutely required for the cochlear duct to elongate and for correct cellular patterning6. As this is regulated via activation of the PCP pathway, one of the most striking phenotypes of cochlea PCP mutants is a shortened cochlear duct with disorganized sensory epithelia7. Similarly, mouse mutants, which lack cilia, also exhibit such a convergence and extension phenotype8,9, though precisely how this is regulated remains to be elucidated.

Because convergence and extension processes are critical for the outgrowth of the cochlear duct, and cellular patterning of the sensory epithelia within the cochlear duct, the developing cochlea is an ideal organ in which to examine PCP signaling during vertebrate development. The organ of Corti, the term given to the specialized sensory epithelium that lines the cochlear duct, is comprised of non-sensory supporting cells and mechanosensory hair cells which must be uniformly oriented for the cochlea to function10. The mechanosensory hair cells are so called because of the stereociliary bundles that extend from the cuticular plate (apical surface) of each sensory hair cell11. These act as primary transducers of mechanosensation and despite their nomenclature as stereocilia, are actually comprised of modified actin filament-based microvilli. Within each chevron-shaped hair bundle, three rows of stereocilia are organized in a highly ordered and regular pattern in a stair case-like manner. Real microtubule-based cilia, termed kinocilia, are required for the development and orientation of the stereociliary bundles12. Upon each hair cell, one single kinocilium is physically attached to the stereocilia bundle, located centrally adjacent to the tallest row of stereocilia. The precise function of the kinocilium is unclear, and one hypothesis is that the kinocilium 'pulls' the stereocilia into shape as they mature from microvilli12. In vertebrates, kinocilia in the cochlea are only present transiently and retract from the hair cells in mice prior to the onset of hearing11,13,14.

Complete loss of cilia in the developing cochlea results in severely shortened cochlear ducts, mis-formed and mis-oriented stereociliary bundles, as well as mis-positioned basal bodies8,9. A functional cilium is not just comprised of the ciliary axoneme. Many proteins associated with cilia function occur in complexes localized to cilia-related subdomains such as the basal body, transition zone, or ciliary axoneme15. The basal body, derived from the mother centriole of the centrosome, is also a microtubule-organizing center for microtubules extending away from the cilium into the cell body and can regulate intracellular trafficking as well as ciliary trafficking. The ciliary transition zone is another region where ciliary function is regulated in terms of organizing import and export of ciliary compounds16.

Multiple studies have identified a connection between cilia and non-canonical Wnt (PCP signaling), though the precise mechanism is unclear17. Redundancy of ciliary and PCP genes and the sensitivity of cell polarity to generalized cellular abnormalities, make it difficult to directly link a mutation to PCP-specific deficits. One of the read outs of PCP signaling is the positioning of the basal body and primary cilium, therefore segregating the primary from the secondary defects is challenging. Some studies in zebrafish and mouse mutants have suggested no connection between cilia and Wnt signaling18-20. Discrepancies in the data may reflect species, tissue, or temporal-dependent differences in ciliary contributions towards Wnt signaling. Furthermore, normal Wnt responsiveness might be retained if basal bodies remain functional. A deeper insight into the role of ciliary proteins in cellular signaling pathways and other biological phenomena is crucial for our understanding of cellular and developmental biology, as well as for the development of targeted treatment strategies.

Protokół

Use and euthanize all animals in accordance with institutional and governmental guidelines and regulations, most commonly via CO2 inhalation and cervical dislocation.

1. Preparation of Reagents

NOTE: Prior to beginning, prepare all reagents using analytical grade chemicals. Make solutions using molecular grade distilled and deionized water unless otherwise specified.

- Phosphate buffered saline (1x PBS): Make 1 L of 1x PBS by dissolving 8g NaCl, 0.2g KCl, 1.44g Na2HPO4 and 0.24g KH2PO4 in 1 L of H2O. Adjust the pH to 7.4 with HCl. PBS does not need to be sterile and can be stored at RT. Note that this buffer is made without CaCl2 or MgCl2.

- Paraformaldehyde (4% PFA): Prepare a 4% solution of PFA in 1x PBS in a ventilated fume hood. Add 40g of paraformaldehyde powder to 1 L of 1x PBS. To dissolve, stir and heat to approximately 60 °C, and slowly add NaOH drop wise to raise the pH. Once the powder has dissolved, readjust the pH to 7.4 with HCl. Filter through a 0.45 µM filter and freeze aliquots. Defrost a fresh aliquot for each experiment.

- Triton buffer: Prepare a 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.15 M NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100 solution by dissolving 8.77 g NaCl in 1 L of 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Add 1 ml Triton X-100. Stir to dissolve. Store Triton buffer at RT.

- Triton block: Prepare 10% goat serum in Triton buffer by adding 1 ml of goat serum to 9 ml of Triton buffer. Store at 4 °C. If using primary antibodies raised in mouse, add goat anti-mouse IgG Fab fragments at a dilution of 1 in 200 to the Triton block for the blocking step.

NOTE: If planning to use samples for scanning electron microscopy (SEM), prepare additional reagents as listed below. - Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) with calcium and magnesium: Make a 1x solution of HBSS by diluting from a stock solution in sterile distilled H2O. As HBSS buffer is complicated to make and there are risks involved, it is advisable to order a premade 10x stock solution. The final concentration of HBBS buffer routinely used is the following: 1.26 mM CaCl2, 0.49 mM MgCl2-6H2O, 0.41 mM MgSO4-7H2O, 5.33 mM KCl, 0.44 mM KH2PO4, 4.17 mM NaHCO3, 137.93 mM NaCl, 0.34 mM Na2HPO4, 5.56 mM Dextrose.

- Hepes buffer: Prepare a 0.1 M Hepes solution in 1x HBSS, by dissolving 23.8 g HEPES in 1 L 1x HBSS buffer.

- Scanning electron microscopy fixative (SEM Fix): Prepare fixative for SEM by diluting electron microscopy grade glutaraldehyde (2.5%) and paraformaldehyde (4%) in Hepes buffer. Add CaCl2 to a final concentration of 10 mM.

- 1% Osmium tetroxide (OsO4) in Hepes buffer; 1% Osmium tetroxide in water: Dilute a stock solution of osmium tetroxide in Hepes buffer, and separately in sterile distilled H2O, to a final concentration of 1%. Osmium tetroxide is highly toxic and is most commonly sold as a 4% solution.

- 1% (w/v) Tannic acid: Dissolve 0.5 g tannic acid in 50 ml sterile distilled H2O. Filter sterilize by filtering through a 0.45 pore size filter.

- Graded ethanol solution series: Dilute 200 proof ethanol with sterile distilled H2O to make 30, 50, 70, 90 and 95% ethanol solutions. For the final ethanol rinses, 100% ethanol 200 proof is required. Use a freshly opened bottle of 200 proof ethanol for the final rinses.

2. Choice of Tissue

- Ideally, examine embryos or young pups between the ages of embryonic day 16.5 (E16.5) and postnatal day 3 (P3).

NOTE: Ossification of the bony labyrinth and temporal bones makes dissection progressively more challenging as mice mature. Also kinocilia, the only true microtubule-based cilium found on cochlear hair cells, retracts during development and is no longer present in adult mice. - After fixation, decalcify adult cochleae. Place dissected (see section 3) bony labyrinths, into 2 ml EDTA (4.13% in PBS), pH 7.3, in a microcentrifuge tube for 3 - 4 days with rotation. Replenish EDTA daily. After the tissues have softened, rinse in 1.5 ml or more PBS 3 times for 5 min on a nutator with increased agitation.

3. Cochlea Dissection

- Post euthanization via cervical dislocation or CO2 inhalation (100% CO2 ), remove the head. Use a scalpel blade or small pair of scissors, depending on the size of the animal, to dissect the head along the sagittal mid-line beginning at the nose and extending caudally. Remove the brain from each half of the skull with a pair of forceps. Identify the temporal bones, which contain the developing bony labyrinths of the inner ear (see arrow in Figure 1A).

- Use a pair of forceps to carefully isolate the bony labyrinths from the skull (temporal bones). Do this under a dissecting microscope. Prise away the bony tissue from the skull by running the forceps gently underneath the bony labyrinths. In animals up to P4 the bony labyrinths are still cartilaginous and can be easily removed without breaking.

- Following dissection, use the tip of the dissecting forceps to clear the oval and round windows and make a small hole in the apex of the cochlear spiral. Fix the bony labyrinths before further dissection of the cochlear duct. To allow for easy removal of the tectorial membrane (see 3.7), fix the bony labyrinths in 1.5 ml 4% PFA for 5 min on ice.

NOTE: If removal of the tectorial membrane is not required, longer fixation is advised (see 4.1 - 4.3). Brief fixation of the temporal bones prior to dissection of the cochlear duct aids the dissection process and removal of the tectorial membrane. Post dissection and exposure of the organ of Corti, further fixation is required. - Further dissect the bony labyrinths to expose the cochlear sensory epithelium as follows. Place the bony labyrinths in a black silicone elastomere-coated dissecting dish containing PBS to facilitate dissection. Use minutien pins to immobilize the tissue if required. To use minutien pins, place them through the vestibular portion of the bony labyrinths with the ventral aspect of the cochlear spiral facing upwards.

NOTE: Black silicone elastomere dish: Mix silicone elastomere base component with powdered charcoal to obtain an opaque black color. Add the curing agent and pour into one or more petri dishes (glass or plastic). Dry under vacuum to remove trapped air bubbles. Dry dishes completely prior to use. - Use fine forceps (#5) to remove the outer cartilage exposing the cochlear duct. Start at the oval window; insert the bottom tip of the forceps into the oval window and gently pry open the cartilage, slowly moving upwards towards the apex.

- After exposure of the cochlear duct, remove the ventral surface, the Reissner's membrane. Use a fine pair of forceps to pinch the Reissner's membrane at the base of the cochlear duct and peel it off in an upward motion. Visualize the dorsal aspect of the cochlear duct, including the sensory epithelium.

- Remove the tectorial membrane as described below (optional). For SEM or immunohistochemistry of the kinocilium or stereociliary bundles remove the tectorial membrane.

- Use a very fine pair of forceps (#55 or finer) to pinch the tectorial membrane at the base of the cochlea and peel upwards towards the apex.

NOTE: The tectorial membrane is optically clear which makes it difficult to identify. More often than not the membrane comes off in one piece and although it is not easily visualized, one can feel the resistance as it is pulled off from the exposed organ of Corti. - After exposing the organ of Corti, further fix the tissue as described below. Retain the vestibular region to aid further preparation of the tissues.

4. Fixation

- For regular immunohistochemistry fix the dissected bony labyrinths in 1.5 ml 4% PFA at 4 °C on a nutator for 2 hr.

NOTE: Because of the sensitivity of differing antibodies and antigens, variations in the length and composition of fixation may be required and should be optimized for each antibody. - After fixation, wash the samples by rinsing in 1.5 ml or more PBS 3 times for 5 min on a nutator with increased agitation. Samples can be stored in PBS at 4 °C for several weeks before processing.

- If preparing samples for SEM, fix dissected temporal bones in SEM fix (see 1.7) for 2 hr at RT. Wash by rinsing in 1.5 ml or more Hepes buffer 3 times for 5 min on a nutator with increased agitation. Store in Hepes buffer at 4 °C until further processing. Storage for longer than a couple of weeks is not recommended.

5. Immunohistochemistry

- Perform immunohistochemistry on dissected samples in one well of a flat-bottomed 96 well plate. Alternatively, use a PCR or microcentrifuge tube. It is advisable to retain the vestibular portion of the bony labyrinth to facilitate processing.

- Permeabilize the tissue by incubating in 1.5 ml Triton buffer for 1 hr at RT on a nutator with gentle agitation.

- Block the tissue by incubating in 0.5 ml Triton block for a minimum of 1 hr at RT. If using primary antibodies raised in mouse, add anti-mouse IgG Fab fragments to the block at a dilution of 1 in 200 (see section 1.4). This greatly decreases non-specific binding of anti-mouse IgG to mouse tissue.

- Incubate the tissue with primary antibodies diluted in Triton block O/N at 4 °C with gentle agitation. Antibody dilution depends on antibodies being used (see section 6.1). Alternatively incubate primary antibodies for 2 hr at RT. Ideally use a minimum volume of 0.5 ml primary antibody dilution. If antibody is limited, use the smallest volume of antibody dilution that completely envelops the tissue.

- Wash the tissue by rinsing in 1.5 ml or more Triton buffer, a minimum of 3 times for 15 min, on a nutator with increased agitation.

- Incubate the tissue with fluorescent dye-conjugated secondary antibodies diluted at the manufacturers recommended concentration (typically 1:200-1:1,000) in Triton block for 1 hr at RT on a nutator. Use a minimum volume of 0.5 ml secondary antibody dilution.

- Centrifuge the diluted secondary antibody at 13,000 x g for 3 min prior to use to minimize non-specific binding of secondary antibody aggregates. Shield the tissue from light from this step onwards to avoid photobleaching the fluorescent dyes.

- As in step 5.5, wash the tissue by rinsing in 1.5 ml or more Triton buffer, a minimum of 3 times for 15 min, on a nutator with increased agitation. Store samples in PBS at 4 °C until ready to mount.

6. Antibody Selection

NOTE: The source of recommended antibodies and their dilutions are listed in the Table of Specific Materials and Equipment. Perform antibody incubations as described in section 5.

- To visualize the microtubule-based kinocilium, use a ciliary axoneme marker such as anti-Arl13b (1:1,000) or anti-acetylated-α-tubulin (1:800). Visualize the basal body using an antibody against γ-tubulin (1:200) or any other centrosomal marker.

- To visualize the actin filament-rich stereociliary bundles, add phalloidin (1:300 - 1,000) conjugated to one of several different fluorophores to the secondary antibody incubation. Phalloidin also labels other filamentous actin structures including the cortical actin filaments surrounding the periphery of each epithelial hair cell. This is helpful in determining the outline of each hair cell. Use an alternative membrane marker such as anti-Zo-1 (1:500) if necessary.

- Label cochlear hair cells using antibodies against Myosin VI (1:1,000) or Myosin VIIa (1:1,000). These can be used if assessing cochlea length.

NOTE: Use appropriate fluorescent dye-conjugated secondary antibodies optimized to the microscope requirements.

7. Mounting and Imaging

- Place the sample in a black silicone elastomere dish containing PBS. Using fine forceps, remove the vestibular region from the cochlear spiral.

- Very carefully remove the underlying cartilage and mesenchyme from the cochlear spiral. The remaining cochlear spiral contains the inner sulcus, organ of Corti and outer sulcus.

- Transfer the cochlear spiral into a drop of PBS placed on a microscope slide. If desired, separate the cochlear spiral into pieces equivalent to one turn. This step is not necessary however, and can lead to loss of the tissue. The apical surface (stereocilia side) of the cochlear hair cells should be facing upward towards the coverslip.

- Wick away the PBS with an adsorbent tissue or piece of filter paper and gently reposition the cochlear spiral if the epithelia has shifted and overlaps onto itself.

- Add a drop of mounting media directly onto the cochlea sample and gently place a coverslip on top, taking care to avoid air bubbles. No spacers are required; place the coverslip directly onto the sample. A water-soluble, non-fluorescing, semi-permanent mounting medium which does not require additional steps to hold the coverslip in place is recommended. Mounting media and coverslip thickness should be matched to microscope specifications.

- Use an epifluorescent or laser-scanning confocal microscope equipped with high magnification (63 - 100X), high numerical aperture (1.2 - 1.4) objectives to capture images of the apical surface of the cochlear hair cell. Use lower objectives (5 - 20X) to take overlapping images of the cochlear spiral to quantify the length of the cochlear duct. Match excitation lasers and emission filters to fluorophores used for secondary antibodies.

8. Scanning Electron Microscopy

- Continue from section 4.3. After washing SEM fixed samples in Hepes buffer, perform the following steps under ventilation. The following protocol works well for cochlea tissue and avoids the use of sputter coating with a conductive metal.

- Post-fix in 1% OsO4 in Hepes buffer for 1 hr, followed by 3 washes with 1 ml distilled water for 5 min each. The smallest volume of OsO4 that completely envelops the tissue should be used to minimize toxic waste. No agitation is required.

- Incubate samples at RT in each of the following solutions for 1 hr with 3 washes with 1 ml distilled water for 5 min each in between steps: 1% Tannic acid freshly made in water and filtered prior to use; 1% OsO4 in water,1% Tannic acid in water,1% OsO4 in water.

- Dehydrate samples through a graded ethanol series by incubation for 10 min in each of the following dilutions: 30, 50, 70, 90, and 95%. No agitation is required.

- Transfer samples through three changes, 5 min each, of 100% ethanol (from a newly opened bottle of 200 proof ethanol).

- Run the samples though a critical point drier following manufacturer's instructions.

- Mount the samples using conductive carbon adhesive on top of an SEM stub prior to imaging on an electron microscope. Under a stereomicroscope, use a pair of fine forceps and a paintbrush to gently position the sample with the cochlear epithelia facing up. Use the vestibular portion of the sample to 'anchor' the tissue to the stub. Store samples in a desiccator until imaging. Perform SEM imaging as described in Jones (2012)21.

9. Quantification

- After immunohistochemistry preparation, acquire images using an epifluorescent or laser-scanning confocal microscope. After preparation for SEM, use a scanning electron microscope to image the specimens. Image the apical surface of the organ of Corti with the exposed cochlear hair cells and intercalated support cells.

- Define specific positions along the cochlear duct, such as 25, 50, and 75% from the base and use these to compare cochlea regions between mutant and control samples. Analyze and compare cilia mutants with their littermate controls, as differences in genetic background can modify the cochlear phenotype.

NOTE: The organ of Corti develops in a gradient that extends from the mid-base towards both the apex and the base. In the mouse, development is not complete until P14, so it is important to compare regions at similar developmental stages and positions. - Take pictures using software accompanying the microscope that allow for quantification of the particular phenotype as required (see below). Use image analysis software such as Image J or software accompanying the microscope to measure lengths, count cells and determine protein localization as described below. Graph these data as a bar chart, scatter plot, box blot or histogram, comparing mutant vs. control.

- Total length of the cochlear duct (Figure 3A):

- Using a hair cell marker or phalloidin, (which marks the stereociliary bundles), determine and measure where the sensory epithelium begins and ends. The length of the cochlear duct is often shortened in cilia mutants.

- Stereociliary bundle abnormalities (Figure 3B,D,E,G):

- Measure bundle convexity (height) as the shortest distance between the vertex of the bundle and the line that extends through both ends of the bundle 'arms' as shown in Figure 3G, left. Alternatively, quantify the area encompassed by the arms of outer hair cell stereociliary bundle as shown in Figure 3G, right. If hair cells with circular stereociliary bundles can be identified count these as a percentage of total hair cells.

NOTE: In many ciliary mutants bundle abnormalities can be observed irrespective of bundle orientation. It is difficult to accurately quantify stereociliary bundle abnormalities.

- Measure bundle convexity (height) as the shortest distance between the vertex of the bundle and the line that extends through both ends of the bundle 'arms' as shown in Figure 3G, left. Alternatively, quantify the area encompassed by the arms of outer hair cell stereociliary bundle as shown in Figure 3G, right. If hair cells with circular stereociliary bundles can be identified count these as a percentage of total hair cells.

- Orientation of the stereociliary bundles (Figure 3B,C,G):

- Assess the orientation of each individual bundle relative to a line extending perpendicular to the row of pillar cells that separates the inner and outer hair cells. Cells with a normal orientation are aligned along this perpendicular axis and so have a rotation of 0°. Determine angles of rotation using either a 360° notation or as absolute deviations from 0°.

- Kinocilia positioning or stereociliary bundle positioning (Figure 3B,F,H):

- Count the percentage of cells in which kinocilia are missing. Measure the distance from the kinocilium to the 'vertex' or center of the bundle. The 'vertex' of the bundle may not be easy to define if bundles are abnormal, and so the center of the bundle can be used instead.

- Quantify the position of kinocilia and stereociliary bundles on the apical hair cell surface, by overlaying a positional grid onto each hair cell and marking the location of either the base of the kinocilium or the vertex/center of the stereociliary bundle. Display the data as a percentage of each category that lies within a specific region of the grid, and by overlaying the locations of each marking onto one positional grid.

NOTE: In control tissues, kinocilia are always attached to the vertex of the stereociliary bundle. In cilia mutants, kinocilia are often missing, mislocalized yet still attached, or even completely detached from the stereociliary bundle. - Kinocilia length (Figure 3I):

- Measure the length of the kinocilium by labeling with a ciliary axoneme marker. Only measure kinocilia that lie flat within a 1.5 µm confocal plane. Confirm that cilia are lying flat by observing a cross-sectional view of the scanned tissue. Compare aged matched samples from the same region of the cochlea since the kinocilium retracts during development.

- Mislocalization of polarity proteins:

- Following immunohistochemistry using antibodies against polarity proteins such as Vangl2 and Gαi3, determine the localization via imaging.

NOTE: In some cilia mutants, localization of polarity proteins is disrupted. These include Vangl2 and Gαi3, which have been shown to be disrupted in Ift20, Bbs8 and Bbs6 mutant cochlea.

NOTE: Further examples for how to quantify and display hair cell polarity can be found in the following papers. Curtin, et al. (2003) Current Biology22, Montcouquiol, et al. (2003) Nature7, Wang, et al (2006) The Journal of Neuroscience23, Montcouquiol, et al. (2008) Methods in Molecular Biology24, May-Simera, et al. (2012) Methods in Molecular Biology25, Yin et al (2012) PloS one 26.

Wyniki

Cochlea Dissection and Tissue Preparation

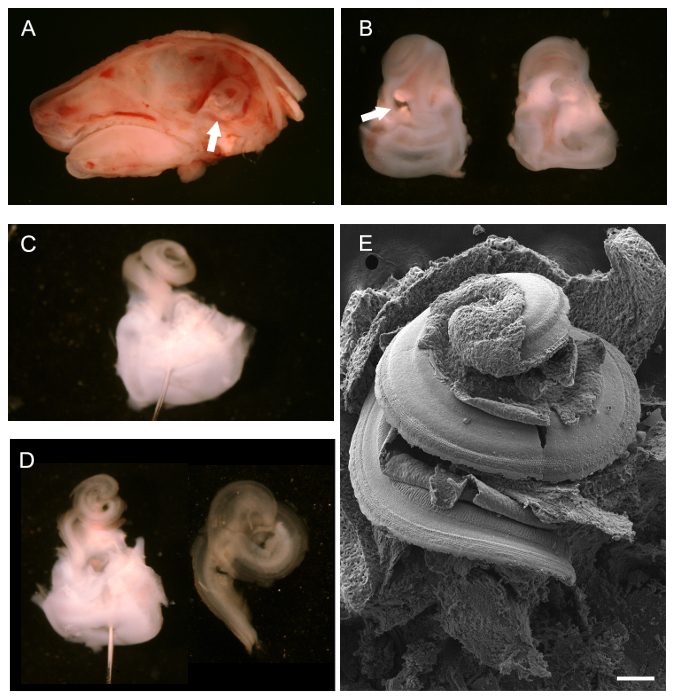

After removal of the brain, post mid-line sagittal dissection of a P0 mouse head, the bony labyrinth, seen from behind, can be visualized (Figure 1A, white arrow) and removed. Figure 1B shows the isolated bony labyrinths with the cochlear hair facing upwards, ventral, (left) and from behind, dorsal (right). The white arrow points to the oval window from which one can begin removing the outer cartilage. Once the outer cartilage has been completely removed, the exposed cochlear duct, still intact, can be observed (Figure 1C). Positioning of a pin through the vestibular region to assist dissection is shown. Two pins, placed at different angles can also be used to anchor the tissue. Figure 1D shows the cochlear duct after removal of the Reissner's membrane and the Tectorial membrane (left) and the isolated cochlear epithelial spiral once it has been isolated from the vestibular region in preparation for mounting for immunohistochemistry (right). To give a general idea of what the exposed cochlear hair looks like, an intact SEM preparation is shown in Figure 1E.

Morphology and Immunofluorescence in Control Cochlea

After preparation of the cochlear tissue, the dorsal surface of the cochlear duct containing the organ of Corti is exposed and can been viewed via SEM or immunofluorescent staining. Viewed as a whole-mount preparation, the four rows of mechanosensory hair cells (one row of inner hair cells and three rows of outer hair cells) can be distinguished. Figure 2A shows a low magnification view of the basal turn from an embryonic mouse cochlea, prepared for SEM. Note the uniform orientation and alignment of the actin-based stereociliary bundles. Additionally the morphology of the stereociliary bundles is consistent, each bundle has the classical ")" (on inner hair cells) or "W" (on outer hair cells) shape. Upon closer magnification at this age additional microvilli can be seen not only on the apical surface of the hair cells, but also in-between the hair cells on the supporting cells (Figure 2B). These will recede leaving only three rows of stereociliary bundles on the outer hair cells and two on the inner hair cells in adults. As can be seen in Figure 2C (white arrow), a single microtubule-based kinocilium (a true primary cilium) is located adjacent to the tallest row of stereocilia at the vertex of each stereociliary bundle. These are attached to the bundle via kinocilia links.

Fluorescent labeling with phalloidin, which labels actin, highlights the uniform orientation and shape of the bundles in control tissue (Figure 2D). Cortical actin is also labeled, which is useful to determine the apical circumference of each individual hair cell. Co-labeling with phalloidin and an antibody against Myosin 7a (Figure 2E), a hair cell marker, also helps to differentiate between hair cells and support cells. Myosin 7a is also a useful marker for measuring cochlear duct extension (see Figure 3A). An antibody against acetylated-α-tubulin is commonly used to identify the microtubule-based kinocilium (Figure 2F). As support cells also harbor primary cilia, it is important to distinguish between cilia emanating from hair cells vs. intercalating support cells. An additional membrane marker such as antibodies against ZO-1 (Zona Occludens 1), which clearly outlines the mosaic patterning of the apical membrane of the cochlear duct, is therefore helpful (Figure 2F). Of further consideration is that antibodies against acetylated-α-tubulin also label internal microtubules and so care should be taken when imaging to focus on the hair cell apical surface. The microtubules in the pillar cells are particularly dense (Figure 2G, white asterisk). A combination of phalloidin and anti-acetylated-α-tubulin labeling is often used to simultaneously identify stereociliary bundles and neighboring kinocilia (Figure 2G, white arrow).

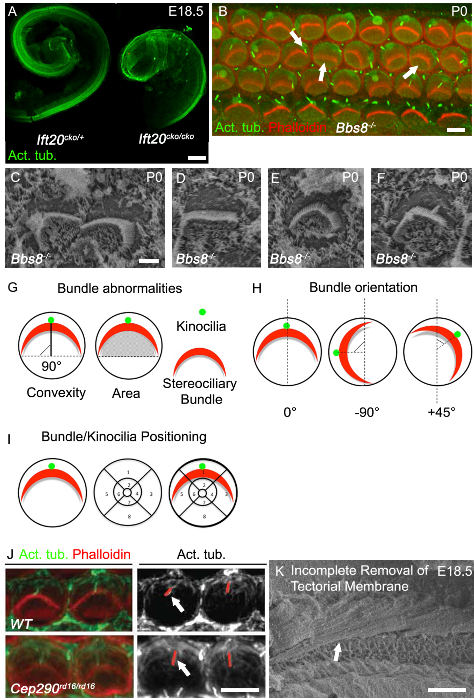

Cochlear Phenotype in Cilia Mutants

Elongation of the cochlear duct is one of the best read outs of convergence and extension defects, and shortened cochlear ducts are commonly observed in classical PCP mutants. The cochlea in ciliary mutants often have shortened cochlear ducts and show a marked broadening of the sensory epithelia at the apex, as can been seen in Ift20cko/cko mice (Figure 3A). Another classical PCP defect is disruption to the uniform orientation of cochlear hair cells, as can be seen in the Bbs8-/- mice both with immunohistochemistry (Figure 3B, right arrow) and with SEM (Figure 3C). In addition to mis-oriented bundles, flattened and misshapen bundles are also commonly observed (Figure 3B, middle arrow; Figure 3D). Often times circular bundles, as can been seen in Figure 3E, are present, especially in hair cells completely devoid of kinocilia. Mis-localization of the kinocilium is also common.

The mis-localized kinocilium may or may not be attached to the stereociliary bundle (Figure 3B, left arrow; Figure 3F). Examples of how to quantify bundle orientation and kinocilia or bundle positioning are shown in Figure 3G and 3H. The orientation of each individual bundle can then be assessed by determining the rotation of the of bundle relative to a line extending perpendicular to the row of pillar cells that separates the inner and outer hair cells. Cells with a normal orientation are aligned along this perpendicular axis and so have a rotation of 0° (Figure 3G). The position of the kinocilium, or center of the stereociliary bundle, can be plotted by overlaying a positional grid on the lumenal surface of the hair cells and then determining the location of the kinocilia or bundle within the grid (Figure 3I). Mutations in cilia genes often affect cilia length, and so the length of the kinocilium can be assessed. In Cep290rd16/rd16 mutants, kinocilia are longer than in controls (Figure 3J). As the cilium retracts, it is critical to have age matched litter mates and to take measurements from the same region of the cochlea. To get good images for analysis and quantification, for both immunohistochemistry and SEM, it is critical to remove the tectorial membrane. Figure 3F shows an SEM micrograph in which the tectorial membrane has not been completely removed.

Figure 1. Dissection of a Developing Mouse Cochlea (P0). (A) Mid-line sagittal dissection of P0 mouse head with brain removed. The white arrow points to the position of the bony labyrinth. (B) Ventral (left) and dorsal (right) views of dissected bony labyrinths. The cochlea is located towards the top with the vestibular portion at the bottom White arrow points to the oval window. (C) The bony labyrinth after removal of the outer cartilage of the cochlea. A pin has been placed through the vestibular system. (D) Left, same view as in C after removal of the Reissner's membrane and Tectorial membrane. Right, isolated cochlear duct ready for mounting. (E) Scanning electron micrograph of an intact, exposed cochlear spiral exposing the floor of the cochlear duct, including the sensory epithelium. Scale bar is 100 µm. (A - D) adapted from May-Simera et al., 201225 Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2. Morphology and Immunofluorescence in Control Cochlea. (A - C) Scanning electron micrographs of the basal turn in embryonic (E18.5) wild type cochleae. One row of inner hair cells (bottom) and three rows of outer hair cells (top) are separated and intercalated by support cells. Chevron-shaped stereociliary bundles uniformly orient towards the lateral edge of each hair cell (upper edge of image). At E18.5 additional microvilli cover the apical surfaces of hair cells, below the stereociliary bundles, and intercalated support cells (B). (C) A single microtubule-based kinocilium (white arrow), is located at the vertex of the bundle, shown here from the lateral edge. (D - G) Immunofluorescent staining of basal turn post natal day 1 (P1) wild type cochleae. Phalloidin labels filamentous actin in stereocilia and cortical actin at the cell periphery (D, E, G). Myosin 7a is a marker for inner and outer hair cells (E). Zo_1 labels the tight junctions in-between cells, making it a great marker to distinguish cell boundaries (F). Acetylated α-tubulin is used as a marker for the kinocilium at the vertex of the bundle (F, G white arrow). Internal microtubules are also labeled by acetylated α-tubulin, which are particular abundant in pillar cells (G white asterix). Scale bars A: 10 µm, B: 5 µm, C: 1 µm, D-G: 5 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3. Cochlear Phenotype in Cilia Mutants. (A) Marked shortening of Ift20cko/cko cochlear ducts compared to control. Dissected cochlear ducts at E18.5 stained with acetylated tubulin. (B) Whole mount images of basal cochlear turn in Bbs8-/- mutant (P0). Phalloidin-labeled filamentous actin, stereocilia (red), acetylated tubulin, kinocilia (green). Stereociliary bundles in Bbs8-/- cochleae are variably rotated (right arrow), flattened and/or mislocalized (middle arrow). Kinocilia are mislocalized or axonemes are missing (left arrow). (C - F) Higher magnification SEM of stereociliary bundles and kinocilia in Bbs8-/- OHCs. In C, rotated bundles, in D, flattened bundle, in E, circular bundles and in F mislocalized kinocilia. (G - I) Schematic representations of bundle abnormality quantification. (G) Left, bundle convexity (height); the shortest distance between the vertex of the bundle and the line that extends through both ends of the bundle 'arms'. As depicted by the solid black line. Right, area under the bundle; the area. (H) Schematic representations of the criteria used to quantify the orientation of stereociliary bundles. The angle of rotation of the bundle is calculated relative to a line extending perpendicular to the row of pillar cells. (I) Schematic representation of the criteria for positional analysis of kinocilia and stereociliary bundles. A segmented grid is laid over the circumference of the hair cell and the position noted. (J) Higher-magnification image of phalloidin-labeled stereocilia bundles (red) and acetylated tubulin-labeled kinocilia (green) of outer hair cells in P0 cochlea. In the adjacent monochromatic panel, red lines identify the kinocilia, which are longer in Cep29 rd16/rd16 mutants compared to control (white arrows). (K) SEM micrograph of embryonic cochlea with incomplete removal of tectorial membrane. Scale bars A: 100 µm, B: 5 µm, C - F: 2.5 µm, I: 5 µm, J: 50 µm. (A - F) modified from May-Simera et al., 20158, J Reprint with permission from Rachel et al., 201227. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Dyskusje

When preparing cochlear tissue for analysis, there are a few key points to bear in mind. Firstly, differences in genetic background can modify the cochlear phenotype, making it necessary to analyze and compare only littermate controls. Secondly, complete removal of the tectorial membrane is required to obtain the best images with immunohistochemistry and is essential for SEM. The tectorial membrane is an opaque structure and can obscure the cells of the sensory epithelium directly beneath it, making imaging more challenging. Occasionally during processing, the tectorial membrane may shrink back, uncovering the hair cells. Even in these cases removal is strongly advised. This step requires patience and practice. Thirdly, immunohistochemistry using antibodies against ciliary proteins, particularly the ones that localize to the highly compacted basal body, can be challenging and require optimization. Consider performing antigen retrieval, intensifying the permeabilization steps, or decreasing the concentration or time of fixation. Finally, when imaging the kinocilium (the primary cilium found on the cochlear hair cells) keep in mind that it begins to retract from P0 - P1 onwards in a base-to-apex gradient. Therefore, when measuring the length of the kinocilium it is important to compare hair cells from the same region of the cochlea and in age matched animals. The intercalated support cells also have primary cilia, which do not retract. Care must be taken to distinguish between supporting cell cilia and hair cell kinocilia.

As mice mature, it becomes increasingly difficult to cleanly isolate the cochlear sensory epithelia, due to the calcification of the temporal bones and bony labyrinths. Decalcification of the tissue is required, which is not always compatible with further immunolocalization techniques but does allow for examination of the gross phenotype and is also compatible with SEM preparation. Inbred mouse strains often exhibit auditory defects such as hair cell loss or elevated auditory brainstem responses (ABRs), due to mutations in known auditory genes or modifier genes. Therefore it is essential to compare age matched littermate controls or breed onto an alternative genetic background.

One of the limitations of this analysis is that, in mice, the kinocilium begins to retract post birth and is no longer present on adult hair cells. For this reason kinocilia measurements can only be done in developing tissue. Also it is necessary to carefully select age-matched controls for comparisons between mutant and control samples. Another limitation is that ciliary mutant mice analyzed thus far do not display severe auditory dysfunction (i.e., auditory brainstem responses, ABRs or otoacoustic emission, OAEs) even when cochlear development is impaired. Consistent with this, hearing defects are not a common human ciliopathy phenotype. Exceptionally, loss of hearing is one of the primary features of Alström syndrome, caused by mutations in the basal body protein ALMS128,29. This suggests that stereociliary bundle morphology is not necessarily linked to auditory dysfunction in cilia mutants, likely because of corrective reorientation of bundles later in development as has been reported for Vangl2 CKO mutants30. If the ciliopathy spectrum is widened to include Usher Syndrome, the most common congenital cause of deaf-blindness, then auditory dysfunction becomes highly relevant. Recent data has shown that several proteins related to Usher syndrome also localize to the cilium and are involved in ciliary-related processes31, but whether these proteins relate to PCP signaling has not yet been examined.

Until now most ciliary mouse mutants analyzed for cochlear PCP defects have only been vaguely examined. The techniques described in this manuscript allow for an extensive detailing of the cochlear phenotype, which will undoubtedly lead to a more precise understanding of ciliary involvement in establishing vertebrate PCP signaling. Despite the large number of ciliopathy mouse models available, surprisingly few have been analyzed in terms of cochlear PCP defects. A common pitfall associated with these models is embryonic lethality. However, since the developing cochlea can be examined embryonically the role of cilia in PCP in the developing ear can be still be investigated. Furthermore, very early embryonic lethality can be circumvented using conditional knockouts. Foxg1Cre 32 mice, available from JacksonLaboratories, are commonly used to inactivategenes of interestinthedeveloping inner ear from E8.To date, efforts have focused primarily on examining disease-causing ciliopathy genes, however exploration of other cilia related proteins and how these affect PCP signaling during development may provide greater insight into cilia biology and function.

If an auditory phenotype is suspected in the mouse models being analyzed, possible further analyses include audiometric testing of ABRs33 or OAEs34. Cochlear explant extension assays (as described in May-Simera et al., 201225), can also be performed and allow for identification of convergent extension defects at earlier developmental time points. Culturing of cochlea explants also allows for treatment with various signaling activators or inhibitors, which can modify explant extension, thereby contributing to mechanistic understanding of the developmental processes involved. Although it is known that the kinocilium retracts after birth11,13,14, this retraction has not been thoroughly addressed in context of ciliary mutants. It would be of interest to take time-specific measurements of kinocilia emergence and retraction in cilia mutants.Considering that a primary role for ciliary proteins is the movement of cargo along microtubules, it is highly likely that these proteins may also regulate aspects of intracellular trafficking along the cytoskeleton35-37. A subset of cilia proteins have been shown to affect trafficking and asymmetric localization of PCP molecules8. Localization by immunohistochemistry of PCP molecules, particularly membrane-associated proteins such as Vangl2, Frz3 and Dsh, is therefore recommended to establish if PCP molecules are mislocalized. Establishment of polarity appears to be a multifaceted affair, and there is mounting evidence for an additional cell autonomous pathway, which is also required for correct PCP in sensory hair cells38. A recent paper showed that G protein-dependent signaling controls the migration of the cilium in a cell-autonomous manner39. Consistent with a role for ciliary proteins in the localization of polarity molecules, heterotrimeric G-protein alpha-i subunit 3 (Gαi3) localization is disrupted in Bbs8 and Bbs6 knockout cochlea8,39.

Distinguishing the role of individual ciliary components and their distinct effects on PCP signaling will give us greater insight into the role of the cilium in establishing correct polarity. Of particular importance is to distinguish between ciliary proteins functioning in a ciliary context, vs. non-ciliary functions of traditionally considered ciliary proteins, such as their role in regulating non-ciliary related intracellular trafficking. The high degree of regularity in many aspects of cochlear structure, including cellular patterning and stereociliary bundle orientation, makes it possible to detect subtle changes in the development of PCP in response to either genetic or molecular perturbations in cilia related proteins. Considering that there are many ciliary mouse models available, and that the developing mouse cochlea is one of the best places to examine PCP signaling, it is of great interest to learn to what extent individual protein mutations disrupt cochlea development.

Ujawnienia

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Podziękowania

The author would like to thank Matthew Kelley, Tiziana Cogliati, Jessica Gumerson, Uwe Wolfrum, Rivka Levron, Viola Kretschmer and Zoe Mann and for their critical evaluation of the manuscript. This work was funded by the Sofja Kovalevskaya Award (Humbodlt Foundation) and the Johannes-Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany.

Materiały

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Tools/Equipment | |||

| Silicone elastomere - Sylgard 184 | Sigma-Aldrich | 761028-5EA | See Note 2 |

| Micro dissecting scissors-straight blade | Various | ||

| Fine forceps (no. 5 and 55) and blunt forceps | Various | ||

| Dissecting microscope. | Various | ||

| Uncoated glass microscope slides | Various | ||

| Microscope cover slips (22 mm × 40 mm × 0.15 mm) | Various | ||

| Transfer pipettes | Various | ||

| Minutien pins | Fine Science Tools | 26002-10 | |

| SEM sample holder | tousimis | 8762 | |

| Scanning electron microscopy studs | TED PELLA | 16111 | |

| PELCO Tabs: Carbon adhesive | TED PELLA | 16084-3 | |

| Fluorescent Microscope | Various | ||

| Critical Point Dryer | Various | ||

| Scanning Electron Microscope | Various | ||

| Glass microscope slides | Various | ||

| Glass coverslips | Various | ||

| Kimwipe Tissue | Various | ||

| Fine Paint Brush | |||

| Reagents | |||

| 1× Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) | Gibco/Life Technologies | 10010023 | |

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) (EM Grade Required for EM) | Various | Prepare a 4% solution in 1× PBS made fresh each time. EM Grade Required for EM. | |

| 2.5% Glutaraldehyde Grade1 | Sigma-Aldrich | G5882 | |

| Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) | Various | ||

| NaCl | Various | ||

| CaCl 2 | Various | ||

| Triton X-100 | Various | ||

| Normal Goat Serum | Various | ||

| AffiniPure Fab Fragment Donkey Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 715-007-003 | |

| Fluoromount-G Mounting media | SouthernBiotech | 0100-01 | |

| 10× Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) | Gibco/Life Technologies | 14065 | |

| Hepes | Gibco/Life Technologies | 15630-080 | |

| Osmium tetroxide (OsO4 ) | Sigma-Aldrich/Fluka Analytical | 75632 | |

| Tannic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | 403040 | |

| Ethanol 200 proof | Various | ||

| Antibodies | |||

| anti Arl13b | Protein Tech | 17711-1-AP | Suggested concentration 1:1,000 |

| anti acetylated tubulin (611-B1) | Sigma-Aldrich | T6793 | Suggested concentration 1:800 |

| anti gamma tubulin (GTU-88) | Sigma-Aldrich | T6557 | Suggested concentration 1:200 |

| anti Zo_1 | Invitrogen | 40-2300 | Suggested concentration 1:500 |

| Myosin VI | Proteus Biosciences | 25-6791 | Suggested concentration 1:1000 |

| Myosin VIIa | Proteus Biosciences | 25-6790 | Suggested concentration 1:1,000 |

| anti Vangl2 | Merk Millipore | ABN373 | Suggested concentration 1:250 |

| anti Gαi3 | Sigma-Aldrich | G4040 | Suggested concentration 1:250 |

| Alexa Fluor® 488 Phalloidin | Invitrogen/Life Technologies | A12379 | Suggested concentration 1:300 - 1,000 |

| Alexa Fluor® 568 Phalloidin | Invitrogen/Life Technologies | A12380 | Suggested concentration 1:300 - 1,000 |

Odniesienia

- Waters, A. M., Beales, P. L. Ciliopathies: an expanding disease spectrum. Pediatr Nephrol. 26, 1039-1056 (2011).

- May-Simera, H. L., Kelley, M. W. Cilia, Wnt signaling, and the cytoskeleton. Cilia. 1, 7 (2012).

- Ross, A. J., et al. Disruption of Bardet-Biedl syndrome ciliary proteins perturbs planar cell polarity in vertebrates. Nat Genet. 37, 1135-1140 (2005).

- Ezan, J., Montcouquiol, M. Revisiting planar cell polarity in the inner ear. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 24, 499-506 (2013).

- Semenov, M. V., Habas, R., Macdonald, B. T., He, X. SnapShot: Noncanonical Wnt Signaling Pathways. Cell. 131, 1378 (2007).

- Wang, J., et al. Regulation of polarized extension and planar cell polarity in the cochlea by the vertebrate PCP pathway. Nat Genet. 37, 980-985 (2005).

- Montcouquiol, M., et al. Identification of Vangl2 and Scrb1 as planar polarity genes in mammals. Nature. 423, 173-177 (2003).

- May-Simera, H. L., et al. Ciliary proteins Bbs8 and Ift20 promote planar cell polarity in the cochlea. Development. 142, 555-566 (2015).

- Jones, C., et al. Ciliary proteins link basal body polarization to planar cell polarity regulation. Nat Genet. 40, 69-77 (2008).

- Lim, D. J. Functional structure of the organ of Corti: a review. Hearing research. 22, 117-146 (1986).

- Nayak, G. D., Ratnayaka, H. S., Goodyear, R. J., Richardson, G. P. Development of the hair bundle and mechanotransduction. The International journal of developmental biology. 51, 597-608 (2007).

- Denman-Johnson, K., Forge, A. Establishment of hair bundle polarity and orientation in the deveoping vestibular system of the mouse. J. Neurocytol. , 821-835 (1999).

- Sobkowicz, H. M., Slapnick, S. M., August, B. K. The kinocilium of auditory hair cells and evidence for its morphogenetic role during the regeneration of stereocilia and cuticular plates. Journal of neurocytology. 24, 633-653 (1995).

- Denman-Johnson, K., Forge, A. Establishment of hair bundle polarity and orientation in the developing vestibular system of the mouse. Journal of neurocytology. 28, 821-835 (1999).

- van Dam, T. J., et al. The SYSCILIA gold standard (SCGSv1) of known ciliary components and its applications within a systems biology consortium. Cilia. 2, 7 (2013).

- Blacque, O. E., Sanders, A. A. Compartments within a compartment: what C. elegans can tell us about ciliary subdomain composition, biogenesis, function, and disease. Organogenesis. 10, 126-137 (2014).

- Wallingford, J. B., Mitchell, B. Strange as it may seem: the many links between Wnt signaling, planar cell polarity, and cilia. Genes & development. 25, 201-213 (2011).

- Borovina, A., Ciruna, B. IFT88 plays a cilia- and PCP-independent role in controlling oriented cell divisions during vertebrate embryonic development. Cell reports. 5, 37-43 (2013).

- Huang, P., Schier, A. F. Dampened Hedgehog signaling but normal Wnt signaling in zebrafish without cilia. Development. 136, 3089-3098 (2009).

- Ocbina, P. J., Tuson, M., Anderson, K. V. Primary cilia are not required for normal canonical Wnt signaling in the mouse embryo. PloS one. 4, e6839 (2009).

- Jones, C. G. Scanning electron microscopy: preparation and imaging for SEM. Methods Mol Biol. 915, 1-20 (2012).

- Curtin, J. A., et al. Mutation of Celsr1 disrupts planar polarity of inner ear hair cells and causes severe neural tube defects in the mouse. Current biology : CB. 13, 1129-1133 (2003).

- Wang, Y., Guo, N., Nathans, J. The role of Frizzled3 and Frizzled6 in neural tube closure and in the planar polarity of inner-ear sensory hair cells. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 26, 2147-2156 (2006).

- Montcouquiol, M., Jones, J. M., Sans, N. Detection of planar polarity proteins in mammalian cochlea. Methods Mol Biol. 468, 207-219 (2008).

- May-Simera, H., Kelley, M. W. Examining planar cell polarity in the mammalian cochlea. Methods Mol Biol. 839, 157-171 (2012).

- Yin, H., Copley, C. O., Goodrich, L. V., Deans, M. R. Comparison of phenotypes between different vangl2 mutants demonstrates dominant effects of the Looptail mutation during hair cell development. PloS one. 7, e31988 (2012).

- Rachel, R. A., et al. Combining Cep290 and Mkks ciliopathy alleles in mice rescues sensory defects and restores ciliogenesis. J Clin Invest. 122, 1233-1245 (2012).

- Jagger, D., et al. Alstrom Syndrome protein ALMS1 localizes to basal bodies of cochlear hair cells and regulates cilium-dependent planar cell polarity. Human molecular genetics. 20, 466-481 (2011).

- Collin, G. B., et al. The Alstrom Syndrome Protein, ALMS1, Interacts with alpha-Actinin and Components of the Endosome Recycling Pathway. PloS one. 7, e37925 (2012).

- Copley, C. O., Duncan, J. S., Liu, C., Cheng, H., Deans, M. R. Postnatal refinement of auditory hair cell planar polarity deficits occurs in the absence of Vangl2. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 33, 14001-14016 (2013).

- Sorusch, N., Wunderlich, K., Bauss, K., Nagel-Wolfrum, K., Wolfrum, U. Usher syndrome protein network functions in the retina and their relation to other retinal ciliopathies. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 801, 527-533 (2014).

- Hebert, J. M., McConnell, S. K. Targeting of cre to the Foxg1 (BF-1) locus mediates loxP recombination in the telencephalon and other developing head structures. Dev Biol. 222, 296-306 (2000).

- Willott, J. F. Chapter 8, Measurement of the auditory brainstem response (ABR) to study auditory sensitivity in mice. Current protocols in neuroscience. , Unit8 21B (2006).

- Martin, G. K., Stagner, B. B., Lonsbury-Martin, B. L., et al. Chapter 8, Assessment of cochlear function in mice: distortion-product otoacoustic emissions. Current protocols in neuroscience. , Unit8 21C (2006).

- Finetti, F., et al. Intraflagellar transport is required for polarized recycling of the TCR/CD3 complex to the immune synapse. Nature cell biology. 11, 1332-1339 (2009).

- Sedmak, T., Wolfrum, U. Intraflagellar transport molecules in ciliary and nonciliary cells of the retina. J Cell Biol. 189, 171-186 (2010).

- Yuan, S., Sun, Z. Expanding horizons: ciliary proteins reach beyond cilia. Annual review of genetics. 47, 353-376 (2013).

- Tarchini, B., Jolicoeur, C., Cayouette, M. A molecular blueprint at the apical surface establishes planar asymmetry in cochlear hair cells. Developmental cell. 27, 88-102 (2013).

- Ezan, J., et al. Primary cilium migration depends on G-protein signalling control of subapical cytoskeleton. Nature cell biology. 15, 1107-1115 (2013).

Przedruki i uprawnienia

Zapytaj o uprawnienia na użycie tekstu lub obrazów z tego artykułu JoVE

Zapytaj o uprawnieniaThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone