Method Article

Complete Laparoscopic Radical Resection of Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma Type IIIb

In This Article

Summary

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (pCCA) is a highly malignant and aggressive tumor, with radical resection being the only curative treatment available. With continuous advancements in laparoscopic techniques and instruments, laparoscopic radical surgery for pCCA is now considered technically safe and feasible. However, due to the high complexity of the surgery and the lack of evidence-based clinical support, laparoscopic radical surgery for type IIIb pCCA is performed only in a few large hepatobiliary centers. Current guidelines recommend left hemihepatectomy combined with total caudate lobectomy and standardized lymphadenectomy for resectable type IIIb pCCA. Therefore, in this article, we provide a detailed description of the surgical steps and technical points of complete laparoscopic left hemihepatectomy combined with total caudate lobectomy, regional lymphadenectomy, and right hepatic duct-jejunal Roux-en-Y anastomosis in patients with type IIIb pCCA, using fluorescence navigation technology to enhance surgical precision and safety. By adhering to standardized surgical procedures and precise intraoperative techniques, we offer an effective means to improve patient outcomes.

Abstract

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (pCCA) is a highly malignant and aggressive tumor, with radical resection being the only curative treatment available. With continuous advancements in laparoscopic techniques and instruments, laparoscopic radical surgery for pCCA is now considered technically safe and feasible. However, due to the high complexity of the surgery and the lack of evidence-based clinical support, laparoscopic radical surgery for type IIIb pCCA is performed only in a few large hepatobiliary centers. Current guidelines recommend left hemihepatectomy combined with total caudate lobectomy and standardized lymphadenectomy for resectable type IIIb pCCA. Therefore, in this article, we provide a detailed description of the surgical steps and technical points of complete laparoscopic left hemihepatectomy combined with total caudate lobectomy, regional lymphadenectomy, and right hepatic duct-jejunal Roux-en-Y anastomosis in patients with type IIIb pCCA, using fluorescence navigation technology to enhance surgical precision and safety. By adhering to standardized surgical procedures and precise intraoperative techniques, we offer an effective means to improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (pCCA), also known as Klatskin tumor, was first described by Gerald Klatskin and is a malignant tumor that occurs in the bile duct epithelium at the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts1. This disease is highly malignant and aggressive, often presenting with jaundice and cholangitis in advanced stages. Despite advancements in diagnosis and treatment, the prognosis for pCCA remains poor, with radical surgical resection still being the only potentially curative approach. Such surgeries typically involve extensive hepatectomy, bile duct resection, and regional lymphadenectomy2. The goal of surgery is to achieve an R0 resection, which significantly improves patient survival rates3,4. However, the complex anatomy of the hilar region and the tumor's proximity to vital vascular structures make these surgeries highly challenging.

In recent years, the advent of laparoscopic technology has revolutionized surgical oncology, offering potential advantages such as reduced perioperative complications, shorter hospital stays, and faster recovery5,6,7. Nevertheless, the application of laparoscopic surgery in pCCA, particularly for type IIIb cases, remains limited, with only a few reports available3,8. This is primarily due to the technical difficulty in achieving adequate margins and performing complex biliary and vascular reconstructions laparoscopically9. Current guidelines recommend left hemihepatectomy combined with total caudate lobectomy and standardized lymphadenectomy for resectable type IIIb pCCA4,10,11,12. However, evidence supporting the use of laparoscopic methods for this extensive surgery is still accumulating.

This study presents the complete laparoscopic radical resection of type IIIb pCCA. We aim to detail this surgery's techniques and key steps, including left hemihepatectomy, total caudate lobectomy, regional lymphadenectomy, and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. By sharing this protocol, we hope to contribute to the evidence supporting the feasibility and safety of laparoscopic methods in the treatment of type IIIb pCCA, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Protocol

The study follows the human research ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient prior to surgery.

NOTE: The patient was a 65-year-old male presenting with a chief complaint of "generalized jaundice and pruritus for 2 weeks". A computed tomography (CT) scan at an outside hospital revealed a perihilar bile duct mass with intrahepatic bile duct dilation. The surgical instruments and equipment used are listed in the Table of Materials.

1. Preoperative preparation

- Perform routine blood tests preoperatively, including complete blood count, liver and kidney function tests, coagulation profile, and serum tumor markers.

- Draw blood samples, send them to the laboratory for various blood tests, and report the results.

NOTE: Liver function tests showed elevated total bilirubin (230.8 μmol/L) and decreased albumin (35.7 g/L). Serum tumor marker tests revealed elevated carbohydrate antigen carbohydrate antigen 199 (184.46 U/mL)4,12.

- Draw blood samples, send them to the laboratory for various blood tests, and report the results.

- Perform preoperative electrocardiogram (ECG), abdominal CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen, chest CT, and other relevant examinations4,12.

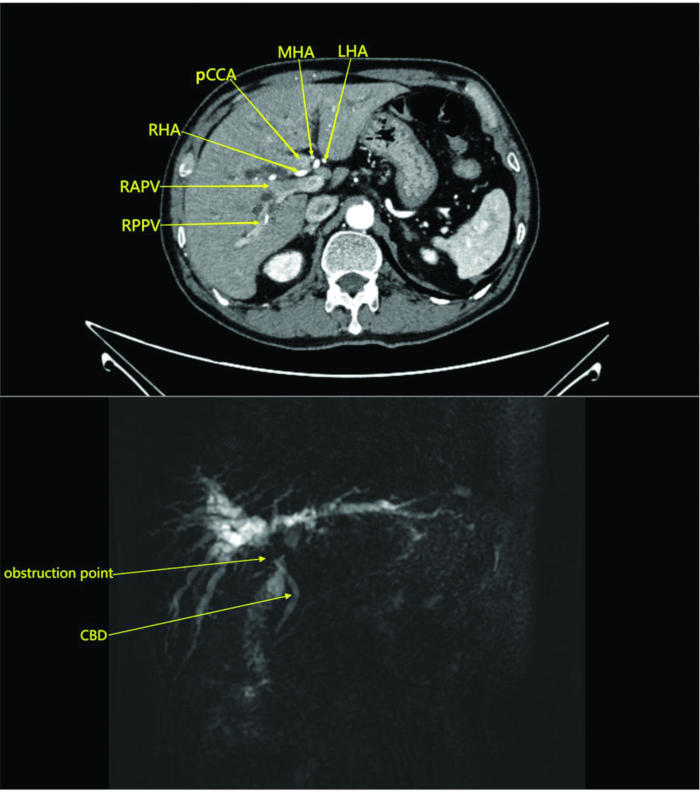

NOTE: In this study, the patient underwent an abdominal CT scan with and without contrast in the radiology department. The scan showed a mass in the perihilar region without involvement of surrounding vessels, suggesting cholangiocarcinoma with obstruction (Figure 1). MRI with and without contrast and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography demonstrated a mass in the perihilar bile duct and adjacent liver parenchyma with intrahepatic bile duct dilatation and enlarged perihilar lymph nodes, indicating a neoplastic lesion (Figure 1).

2. Surgical procedure

- Administer general anesthesia with tracheal intubation, intravenous and inhalational agents. Position the patient supine with the head elevated and legs apart. Perform routine disinfection using povidone-iodine solution.

NOTE: The primary surgeon stands on the patient's right side, the assistant on the left side, and the camera holder between the patient's legs (Figure 2). - Make a longitudinal incision of approximately 1 cm at the umbilicus, insert a Veress needle, and insufflate CO2 to maintain an intra-abdominal pressure of 12 mmHg. Insert a 10 mm trocar and a 30° laparoscope. After confirming no distant metastasis via laparoscopy, place the surgical trocars as shown in Figure 2.

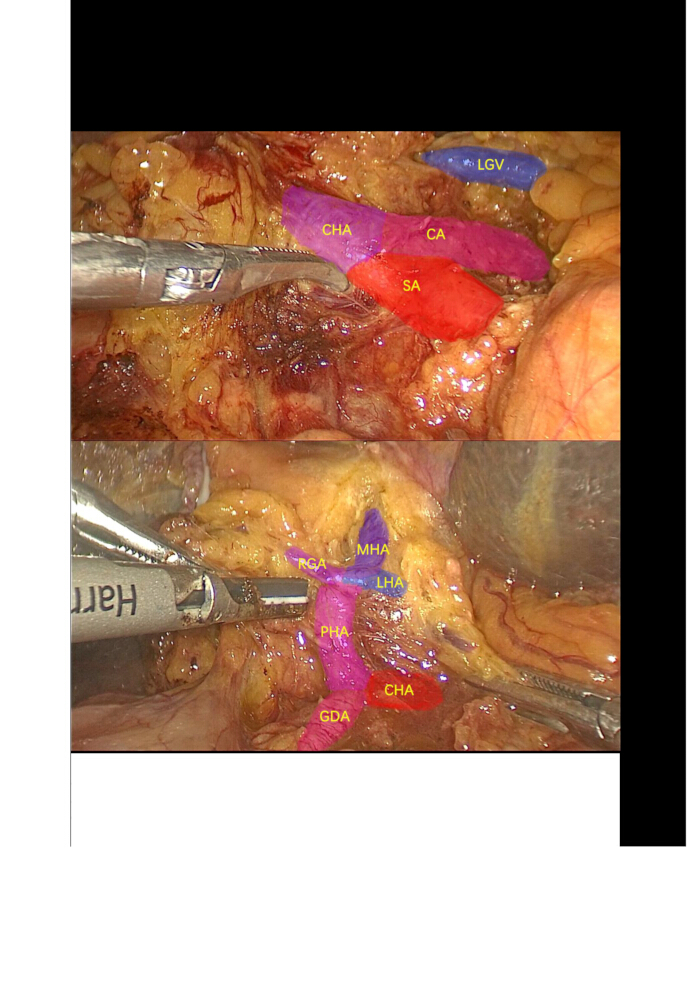

- Dissect the cystic artery and cystic duct, then proceed with the retrograde removal of the gallbladder. Use an ultrasonic scalpel to dissect, mobilize, and suspend the common hepatic artery (CHA), gastroduodenal artery (GDA), proper hepatic artery (PHA), and the left hepatic arteries (LHA) (giving off the middle hepatic artery (MHA)) and right hepatic arteries (RHA). Ligate and divide the right gastric arteries (RGA) and LHA (Figure 3).

- Transect the common bile duct (CBD) at the superior border of the pancreas and send the distal margin for frozen section pathology to confirm negative margins.

- Use an ultrasonic scalpel to dissect, mobilize, and suspend the portal vein (PV). Remove the extrahepatic bile duct and lymph node groups 8, 12, and 13 en bloc along the PV towards the hepatic hilum, achieving skeletonization of the hepatoduodenal ligament.

- Ligate and divide the left branch of portal vein (LPV) and caudate lobe portal vein branches.

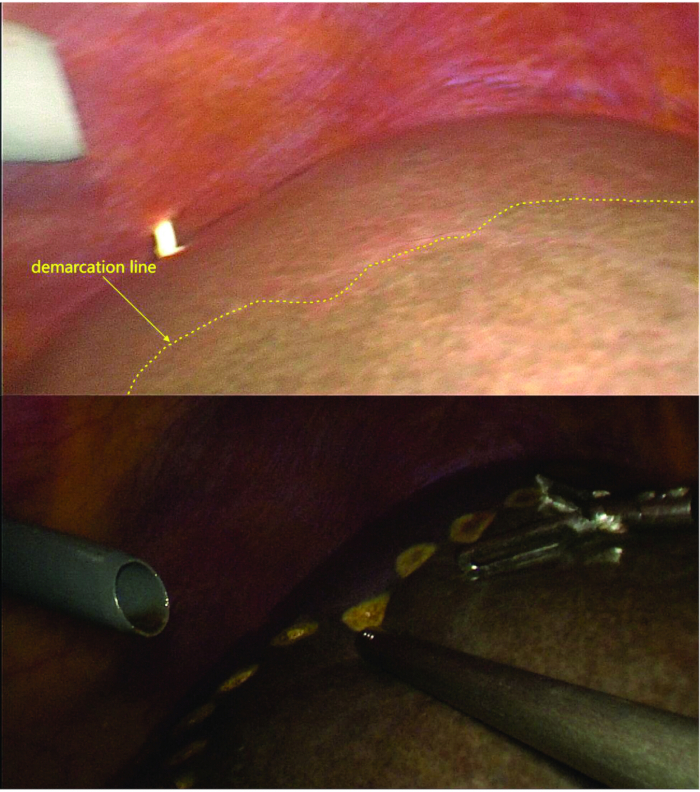

- Dissect the left hepatic ligaments and divide the short hepatic veins of the caudate lobe, clearly delineating the demarcation line (ischemic line) between the right and left liver lobes.

- After marking the demarcation line, confirm that the fluorescence boundary matched the ischemic line using fluorescence imaging (Figure 4, and Figure 5).

NOTE: A negative staining method is used here, with indocyanine green administered via peripheral intravenous injection at a dose of 0.25 mg13,14.

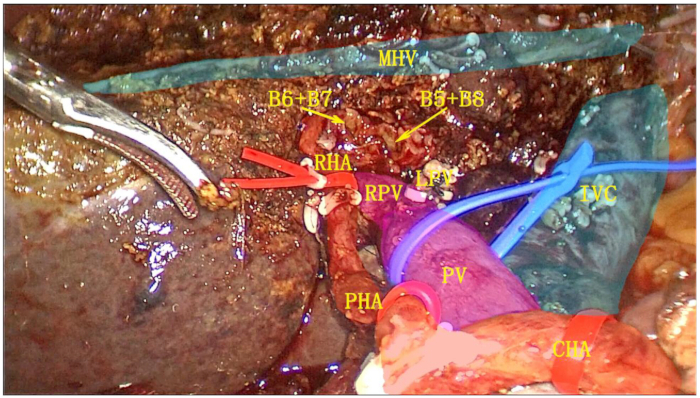

- Intermittently occlude the main PV using the Pringle maneuver15. Use an ultrasonic scalpel to transect the liver parenchyma along the demarcation line, then along the plane of the middle hepatic vein (MHV), ensuring to divide its V4b and V4a branches.

NOTE: Patients with a positive liver margin may consider undergoing expanded left hepatectomy (LH), which involves the complete resection of the main trunk of the MHV and the left portions of segments 5 and 8. This approach may improve survival rates16. - Transect the right hepatic duct approximately 1 cm from the tumor and send the proximal margin for frozen section pathology to confirm negative margins.

- Perform intraoperative frozen section analysis of the proximal hepatic duct margin multiple times as needed to ensure an R0 resection. If the right hepatic duct is extensively divided, consider bile duct reconstruction or double hepaticojejunostomy of the right anterior and right posterior bile ducts.

- Transect the left hepatic vein (LHV) using an endoscopic linear cutter stapler (ENDO-GIA). Completely resect the left hemiliver and the entire caudate lobe, and place the specimen in a retrieval bag (Figure 6).

- Transect the jejunum approximately 20 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz. Elevate the distal loop posterior to the colon for an end-to-side anastomosis with the right hepatic duct, using continuous sutures for the anterior and posterior walls (Figure 7). Perform a side-to-side jejunojejunostomy approximately 45 cm distal to the right hepatic duct-jejunal anastomosis.

- Irrigate the abdominal cavity with sterile distilled water. Carefully inspect the surgical field for active bleeding, bile leaks, and gastrointestinal side branch injuries. Place drainage tubes in the left liver section and Winslow's foramen.

- Extend the umbilical incision by approximately 5 cm and dissect the abdominal wall layer by layer to retrieve the specimen. Verify the count of surgical instruments and gauze. Remove the trocars under direct vision. Close the abdominal wall incision with interrupted 2-0 absorbable sutures to complete the surgery.

3. Postoperative care

- Transport the patient safely back to the ward after the patient regains consciousness.

- Administer intravenous antibiotics, omeprazole, and nutritional support postoperatively.

- Start a liquid diet on the third postoperative day after the patient passes gas.

- Remove the abdominal drainage tubes on the 4th and 13th postoperative days.

Results

The surgery progressed smoothly, and intraoperative frozen section pathology showed negative margins at both the distal and proximal bile ducts. Throughout the procedure, the patient's vital signs remained stable, and anesthesia was effective. The operation lasted 360 min, with PV occlusion time totaling 60 min (15 min + 5 min × 4 times). Intraoperative blood loss was 400 mL, and the patient received 2 units of leukocyte privative red blood cells and 600 mL of fresh frozen plasma. Postoperative flatus was observed 72 h after surgery. There were no complications, such as abdominal bleeding, bile leakage, abdominal infection, or incision infection. The postoperative hospital stay was 14 days. Postoperative paraffin-embedded histopathological analysis showed moderately differentiated biliary adenocarcinoma involving adjacent liver tissue, with no definite vascular invasion and negative liver margins. Sixteen lymph nodes were removed, with no metastasis detected. The tumor was staged as pT2bN0M0, Stage II (Table 1). A CT scan 1 month postoperatively showed successful tumor resection with no evident recurrence or metastasis (Figure 8).

Figure 1: Abdominal CT scan and contrast-enhanced arterial phase images of the patient. The images reveal a mass at the hepatic hilum without invasion of surrounding blood vessels, suggesting cholangiocarcinoma with obstruction. Abbreviations: RAPV: right anterior branch of the portal vein; RPPV: right posterior branch of the portal vein; CBD: common bile duct; RHA: right hepatic artery; pCCA: Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma; MHA: middle hepatic artery; LHA: left hepatic artery. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Position of the surgeon and trocar placement. The surgeon stands as shown in the figure, with the trocars placed in the peritoneal cavity at the positions indicated in the image. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Lymph node dissection. Dissection and isolation of the celiac trunk artery, splenic artery, common hepatic artery, gastroduodenal artery, proper hepatic artery, right gastric artery, left hepatic artery, middle hepatic artery, and surrounding lymph nodes. Abbreviations: CA: Celiac artery; SA: Splenic artery; LGV: Left gastric vein; CHA: common hepatic artery; GDA: gastroduodenal artery; PHA: proper hepatic artery; LHA: left hepatic artery; MHA: middle hepatic artery; RGA: right gastric arteries. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: Dissection of the caudate Lobe. The caudate lobe was dissected along the inferior vena cava (IVC) from the caudal to the cranial direction and from the left to the right side. Upon reaching the right side of the IVC, the left liver was lifted, revealing the IVC, paracaval branch, process branch, and Spiegel lobe from left to right. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5: Marking of the demarcation line. After ligation and transection of the LPV branch, caudate lobe portal vein branch, and short hepatic veins, the demarcation line between the left and right hemilivers is visible. Under fluoroscopy, the demarcation line observed aligns with the ischemic line. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 6: Postoperative cut surface after left hemihepatectomy combined with complete caudate lobe resection. The gallbladder, hepatoduodenal ligament, left hemi-liver, and complete caudate lobe were resected as a single unit. Abbreviations: RPV: right branch of portal vein; IVS: inferior vena cava; MHV: middle hepatic vein; RHA: right hepatic artery; PV: portal vein; PHA: proper hepatic artery; CHA: common hepatic artery. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 7: Postoperative view of pCCA resection. The MHV is fully exposed, and the posterior and anterior walls of the right hepatic duct are anastomosed to the jejunal in a continuous manner. Abbreviations: MHV: middle hepatic vein. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 8: Postoperative CT scan. The postoperative CT scan demonstrates successful tumor resection with no evident recurrence or metastasis. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| Operation time (min) | 360 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 400 |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion (mL) | 1000 |

| PV occlusion time (min) | 60 |

| First flatus (h) | 72 |

| First postoperative liquid diet (days) | 3 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (days) | 14 |

| Postoperative complications (yes/no) | No |

| Bleeding (yes/no) | No |

| Bile leakage (yes/no) | No |

| Abdominal infection (yes/no) | No |

| Incision infection (yes/no) | No |

| Pathological result | Biliary adenocarcinoma |

| Differentiation | Moderate |

| TNM stage | pT2bN0M0 |

| AJCC stage | II |

Table 1: The surgical outcomes of the patient.

Discussion

pCCA is a common malignant tumor of the bile ducts, with radical surgical resection being the only potential curative treatment2. Traditional radical surgery for pCCA typically requires an abdominal incision of 20–30 cm, resulting in significant surgical trauma. Large incisions often cause considerable postoperative pain, affecting patient comfort and recovery, thereby prolonging hospital stays5,6,7. Except for some Type I pCCA that can undergo local bile duct resection and biliary-enteric anastomosis, other types require liver resection, including complete caudate lobe resection11. However, the visual field in open surgery mainly relies on direct visualization by the surgeon, which is limited, especially when handling deep structures. In contrast, laparoscopic technology allows direct visualization under magnification and variable angles, facilitating the identification of anatomical structures and enabling more precise and safer operations. Additionally, laparoscopic technology enables minimally invasive exploration, potentially avoiding unnecessary laparotomies in patients with occult metastases of pCCA17.

Studies have shown that laparoscopy in liver and biliary surgeries offers potential advantages such as reduced perioperative complications, shorter hospital stays, and faster recovery18,19. With the continuous advancement of laparoscopic technology and instruments, laparoscopic radical surgery for pCCA has gradually been implemented clinically. In 2011, Hong Yu et al. first reported laparoscopic radical surgery for 14 cases of Type I and II pCCA20. In 2020, Ratti et al.21provided the first evidence of comparability between open and minimally invasive surgery (MIS) through a propensity score matching analysis. In this well-conducted study, the study demonstrated similar outcomes between open and laparoscopic surgeries21. Over the past decade, there have been reports of laparoscopic radical surgery for pCCA, but most are retrospective studies with insufficient evidence. Current guidelines recommend laparoscopic exploration and biopsy for some pCCA17. Studies have shown no significant differences in R0 resection rates, overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), and complications between open and laparoscopic radical surgery for pCCA22,23,24. Moreover, the introduction of laparoscopic fluorescence imaging technology has further enhanced the precision and safety of surgeries. This technology uses fluorescent dyes that are specifically distributed in tissues, providing real-time imaging through a fluorescence camera system. This helps surgeons distinguish the boundaries between tumor and normal tissues more clearly25,26. In anatomical liver resection, fluorescence imaging technology aids surgeons in delineating the boundaries of liver resection segments more accurately. It demonstrates a higher detection rate for superficial liver lesions compared to conventional imaging, thereby increasing the thoroughness of the resection and the R0 resection rate, ultimately enhancing the oncological radicality of the surgery27,28. However, in patients with cirrhosis, the false positive rate is higher, and fluorescence boundary staining can occur. As hepatobiliary surgeons continue to explore and gain experience in this area, the feasibility and safety of this surgical approach have been further validated.

Traditional radical surgery for Type IIIb pCCA involves left hemihepatectomy combined with complete caudate lobe resection and standardized lymph node dissection. The approach is generally divided into left-side and right-side approaches. The left-side approach first involves the dissection of the lymph nodes adjacent to the common hepatic artery, followed by the lymph nodes in the hepatoduodenal ligament and the posterior margin of the pancreas. The right-side approach starts with the lymph nodes in the posterior margin of the pancreas, followed by the hepatoduodenal ligament lymph nodes and the lymph nodes adjacent to the common hepatic artery. The dissection sequence can be tailored to the characteristics of laparoscopic surgery and the surgeon's habits, selecting the appropriate and standardized regional lymph node and nerve plexus dissection sequence based on intraoperative anatomical structures.

For this patient, preoperative imaging did not reveal any signs of lymph node metastasis. Therefore, we adopted the conventional left-side approach, sequentially dissecting the lymph nodes adjacent to the common hepatic artery, the hepatoduodenal ligament, and the posterior margin of the pancreas from the caudal side to the cranial side. The distal bile duct margin was excised and sent for intraoperative frozen section pathology, which confirmed negative margins. We then performed left hemihepatectomy combined with complete caudate lobe resection and excised the proximal bile duct margin, which also showed negative margins on intraoperative frozen section pathology, achieving R0 resection.

Studies have shown that patients with pCCA who achieve R0 resection have significantly better OS and DFS compared to those with R1 resection. Current guidelines also indicate that achieving R0 resection through segmental hepatectomy combined with complete caudate lobe resection and standardized lymph node dissection is crucial. However, due to technical difficulties and insufficient evidence, only a few high-volume hepatobiliary centers are currently performing laparoscopic radical surgery for pCCA, with most reports coming from Eastern countries22. Additionally, in the early stages of developing this technology, longer operative times and a steep learning curve are required, which are limitations of this technique. Currently, there are no studies indicating the required time and number of surgeries for surgeons to master this complex procedure. The only guidance comes from the Expert Group on Operational Norms of Laparoscopic Radical Resection of Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma in China, which suggests that the learning curve for performing laparoscopic liver resection and laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy should involve more than 50 cases each. Existing data is still insufficient to demonstrate the superiority of one technique over another or to compare outcomes with open methods. Therefore, we recommend that a specialized team of minimally invasive surgeons at major hepatobiliary centers, after overcoming the learning curve, selectively choose suitable cases (with no contraindications for standard laparoscopic or open radical resection of pCCA, and no invasion of the portal vein or hepatic artery). The surgeons should first attempt laparoscopic radical surgeries for Type I and Type II pCCA before progressing to Type IIIb laparoscopic procedures. This approach will help ensure safe postoperative outcomes, sufficient tumor resection, and appropriate identification and management of potential complications.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82060454), the key research and development program of Jiangxi Province of China (20203BBGL73143), and the Jiangxi Province high-level and high-skill leading talent training project (G/Y3035).

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 5-mm trocar | CANWELL MEDICAL Co., LTD | 179094F | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

| 12-mm trocar | CANWELL MEDICAL Co., LTD | NB12STF | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

| Absorbable Sutures | America Ethicon Medical Technology Co., LTD | W8557/W9109H/VCPB839D | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

| Alligaclip Absorbable Ligating Clip | Hangzhou Sunstone Technology Co., Ltd. | K12 | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

| Endoscopic linear cutting stapler | America Ethicon Medical Technology Co., LTD | ECR60W/PSEE60A | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

| Non-absorbable polymer ligature clip | Greiner Bio-One Shanghai Co., Ltd. | 0301-03M04/0301-03L04/0301-03ML02 | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

| NonAbsorbable Sutures | America Ethicon Medical Technology Co., LTD | EH7241H/EH7242H | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

| Ultrasonic scalpel | America Ethicon Medical Technology Co., LTD | HARH36 | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

References

- Klatskin, G. Adenocarcinoma of the hepatic duct at its bifurcation within the porta hepatis: An unusual tumor with distinctive clinical and pathological features. Am J Med. 38 (2), 241-256 (1965).

- Cillo, U., et al. Surgery for cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Int. 39 Suppl 1 (Suppl Suppl 1), 143-155 (2019).

- Jingdong, L., et al. Minimally invasive surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: A multicenter retrospective analysis of 158 patients. Surg Endosc. 35 (12), 6612-6622 (2021).

- Vogel, A., et al. Biliary tract cancer: Esmo clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 34 (2), 127-140 (2023).

- Giannini, A., et al. The great debate: Surgical outcomes of laparoscopic versus laparotomic myomectomy. A meta-analysis to critically evaluate current evidence and look over the horizon. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 297, 50-58 (2024).

- Hakkenbrak, N. A. G., Jansma, E. P., Van Der Wielen, N., Van Der Peet, D. L., Straatman, J. Laparoscopic versus open distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A review and meta-analysis. Surgery. 171 (6), 1552-1561 (2022).

- Macacari, R. L., et al. Laparoscopic vs. Open left lateral sectionectomy: An update meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg. 61, 1-10 (2019).

- Zhou, Y., Cai, P., Zeng, N. Augmented reality navigation system makes laparoscopic radical resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma type b more precise and safe. Gastrointest Surg. 28 (7), 1212-1213 (2024).

- Hu, H. J., et al. Hepatic artery resection for bismuth type iii and iv hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Is reconstruction always required. J Gastrointest Surg. 22 (7), 1204-1212 (2018).

- Rushbrook, S. M., et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cholangiocarcinoma. Gut. 73 (1), 16-46 (2023).

- Xiong, Y., Jingdong, L., Zhaohui, T., Lau, J. A consensus meeting on expert recommendations on operating specifications for laparoscopic radical resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Front Surg. 8, 731448(2021).

- Benson, A. B., et al. Hepatobiliary cancers, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 19 (5), 541-565 (2021).

- Kokudo, N., Ishizawa, T. Clinical application of fluorescence imaging of liver cancer using indocyanine green. Liver Cancer. 1 (1), 15-21 (2012).

- Terasawa, M., et al. Applications of fusion-fluorescence imaging using indocyanine green in laparoscopic hepatectomy. Surg Endosc. 31 (12), 5111-5118 (2017).

- Pringle, J. H. V. Notes on the arrest of hepatic hemorrhage due to trauma. Ann Surg. 48 (4), 541-549 (1908).

- Otsuka, S., et al. Efficacy of extended modification in left hemihepatectomy for advanced perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: Comparison between H12345'8'-B-MHV and H1234-B. Ann Surg. 277 (3), e585-e591 (2023).

- Roth, G. S., et al. Biliary tract cancers: French national clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatments and follow-up (TNCD, SNFGE, FFCD, UNICANCER, GERCOR, SFCD, SFED, AFEF, SFRO, SFP, SFR, ACABI, ACHBPT). Eur J Cancer. 202, 114000(2024).

- Abu Hilal, M., et al. The Southampton consensus guidelines for laparoscopic liver surgery: From indication to implementation. Ann Surg. 268 (1), 11-18 (2018).

- Tang, W., et al. Minimally invasive versus open radical resection surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Comparable outcomes associated with advantages of minimal invasiveness. PLoS One. 16 (3), e0248534(2021).

- Yu, H., Wu, S. -D., Chen, D. -X., Zhu, G. Laparoscopic resection of bismuth type I and II hilar cholangiocarcinoma: An audit of 14 cases from two institutions. Dig Surg. 28 (1), 44-49 (2011).

- Ratti, F., et al. Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: Are we ready to step towards minimally invasiveness. Updates Surg. 72 (2), 423-433 (2020).

- Berardi, G., et al. Minimally invasive surgery for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: A systematic review of the short- and long-term results. Cancers (Basel). 15 (11), 3048(2023).

- Xiong, F., Peng, F., Li, X., Chen, Y. Preliminary comparison of total laparoscopic and open radical resection for hepatic hilar cholangiocarcinoma a single-center cohort study. Asian J Surg. 46 (22), 856-862 (2023).

- Qin, T., et al. The long-term outcome of laparoscopic resection for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma compared with the open approach: A real-world multicentric analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 30 (3), 1366-1378 (2023).

- Urade, T., et al. Laparoscopic anatomical liver resection using indocyanine green fluorescence imaging. Asian J Surg. 43 (1), 362-368 (2020).

- Ishizawa, T., et al. Real-time identification of liver cancers by using indocyanine green fluorescent imaging. Cancers. 115 (11), 2491-2504 (2009).

- Xu, C., Cui, X., Jia, Z., Shen, X., Che, J. A meta-analysis of short-term and long-term effects of indocyanine green fluorescence imaging in hepatectomy for liver cancer. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 42, 103497(2023).

- Tangsirapat, V., et al. Surgical margin status outcome of intraoperative indocyanine green fluorescence-guided laparoscopic hepatectomy in liver malignancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Surg. 24 (1), 181(2024).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved