Metacognitive Development: How Children Estimate Their Memory

Обзор

Source: Laboratories of Judith Danovitch and Nicholaus Noles—University of Louisville

Human memory is fallible, and people often cannot accurately recall what they have seen or heard. Adults are aware of their limited memory capacity, so they use strategies, such as rehearsal and mnemonic devices, to improve their recall of important information. Because adults understand the limits of memory, they know it makes more sense to write down the items on their shopping list rather than to try to remember the items when they get to the store. This ability to think about one’s own memory is called metamemory. Metamemory is one component of a broader set of cognitive processes that allow humans to think about their own knowledge and thinking, which is called metacognition.

Although young children understand that people have thoughts and a limited amount of knowledge, they often have trouble acknowledging the limits of their own knowledge and cognitive skills. Children’s ability to accurately estimate their own memory capacity and abilities improves over the elementary school years. One common way of measuring metamemory and its development is by giving children an opportunity to predict how well they can remember something, and then observing how well their prediction matches their actual recall.

This experiment demonstrates how to measure children’s metamemory based on the methods developed by Shin, Bjorklund, and Beck.1

Процедура

Recruit children between ages 6 and 9. For the purposes of this demonstration, only one child is tested. Larger sample sizes (as in the Shin, Bjorklund, and Beck study1) are recommended when conducting any experiments.

Participants should have no history of developmental disorders and have normal hearing and vision.

1. Prepare study materials.

- Create a set of 18 cards with a black-and-white picture of a common object and the printed name of the object on each card.

- An example list of objects is: bicycle, bus, ship, truck, train, taxi, grapes, watermelon, banana, strawberry, cherry, lemon, crocodile, deer, pig, bear, squirrel, and zebra.

- Create and print a number line showing the numbers 1-18.

2. Data collection

- Memory estimation

- Sit the child on the opposite side of the table as the experimenter.

- Explain that the child is going to be playing a memory game. Tell the child, “I am going to show you 18 pictures. You will have two minutes to study them any way you like.”

- Ask the child, “How many of the 18 pictures do you think you will remember?” and show the child the number line.

- Record the child’s response.

- Picture presentation

- Present the child with each of the 18 cards one at a time.

- When presenting each card, ask the child to name the object on the card or read the label. Correct any errors.

- After the child has named the picture, place the card face up on the table.

- Study

- When all 18 cards have been presented and are on the table, tell the child that they will have two minutes to study the cards.

- Set a timer for 2 min.

- Allow the child to study the cards in any way they see fit.

- Notify the child when time is up, then pick up and put away the cards.

- Delay

- The goal of this portion of the procedure is to create a buffer between study and test, in order to ensure that the child is not continuing to rehearse the studied items.

- Give the child a set of puzzles or mazes and ask the child to complete them.

- Set a timer and allow the child to work on the puzzles or mazes for 5 min.

- Memory test

- Ask the child to recall as many of the 18 items as possible.

- Record the child’s responses.

- If the child has not recalled any items for approximately 10 s, ask the child if they remember anymore items.

- If the child responds that they do not remember anything else, then encourage them to keep trying to remember any other items.

- If the child fails to recall any items for approximately 10 s this time, end the memory test session and thank the child for their participation.

3. Analysis

- The dependent variables in this study are the number of objects the child predicted they would remember (0-18) and the total number of objects the child actually recalled during the memory test (0-18).

- Calculate each child’s prediction accuracy by subtracting the actual number of items recalled from the predicted value. This score can be positive, indicating overestimation, or negative, indicating underestimation.

- Calculate the percentage of children who overestimate their memory for each age group, and compare these percentages by using a chi-square test.

Результаты

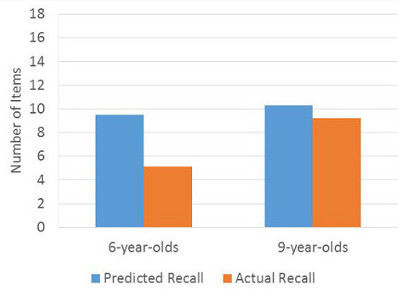

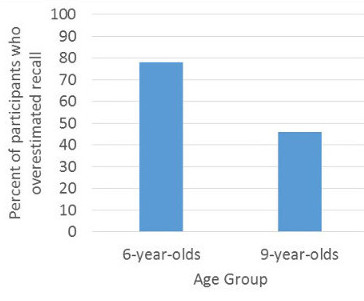

Researchers tested 32 6-year-olds and 32 9-year-olds and found that children’s predictions improved with age (Figure 1). Older children predicted they would remember less items than younger children, yet the total number of items they actually recalled was higher. The average prediction accuracy score for 6-year-olds was 4.19, indicating that they consistently overestimated their memory. The average prediction accuracy score for 9-year-olds was 1.02, indicating that their predictions about their memory were more realistic. Similarly, 78% of 6-year-olds overestimated their memory, but only 46% of 9-year-olds did so (Figure 2). Chi-square tests comparing the number of children who overestimated their memory across age groups were significant at the p < 0.05 level.

Figure 1. Average predicted and actual recall for children in each age group (out of 18 items).

Figure 2. Percentage of children at each age who overestimated their memory.

Заявка и Краткое содержание

Children’s tendency to overestimate their knowledge and abilities, including their memory, has consequences for their behavior in a number of situations. In the classroom, thinking that they remember or know more than they do can make it hard for children to understand the value of studying or rehearsing new information. Even when young children are faced with direct evidence of their limitations (e.g., failing to remember items in a memory test), they often persist in overestimating their abilities.

This excessively positive view of themselves can also have consequences for children’s physical well-being, as younger children are more likely to engage in a dangerous behavior, like a bicycle stunt, because they believe they are capable of doing so successfully. Older children who realize their limitations are less likely to risk activities well outside of their capabilities.

Although it may seem like overestimating yourself and having poor metacognitive awareness would only have negative consequences for young children, some researchers have proposed that children’s overestimation of their abilities is beneficial in some ways, as well. In reality, young children are not very capable. They still have a lot to learn, and it may be that having a true understanding of the limits of their knowledge, memory, strength, etc., would decrease their motivation to try new things or face a challenging task. However, because children believe they are capable, and in some ways invincible, they are willing to take on challenges, like learning to multiply or doing a cartwheel. Thus, thinking that they will succeed (even if it is actually unlikely) can help motivate children to try new activities and learn more about the world.

Ссылки

- Shin, H., Bjorklund, D. F., & Beck, E. F. The adaptive nature of children's overestimation in a strategic memory task. Cognitive Development. 22 (2), 197-212 (2007).

Перейти к...

Видео из этой коллекции:

Now Playing

Metacognitive Development: How Children Estimate Their Memory

Developmental Psychology

10.4K Просмотры

Habituation: Studying Infants Before They Can Talk

Developmental Psychology

54.1K Просмотры

Using Your Head: Measuring Infants' Rational Imitation of Actions

Developmental Psychology

10.2K Просмотры

The Rouge Test: Searching for a Sense of Self

Developmental Psychology

54.3K Просмотры

Numerical Cognition: More or Less

Developmental Psychology

15.0K Просмотры

Mutual Exclusivity: How Children Learn the Meanings of Words

Developmental Psychology

32.9K Просмотры

How Children Solve Problems Using Causal Reasoning

Developmental Psychology

13.1K Просмотры

Executive Function and the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task

Developmental Psychology

15.0K Просмотры

Categories and Inductive Inferences

Developmental Psychology

5.3K Просмотры

The Costs and Benefits of Natural Pedagogy

Developmental Psychology

5.2K Просмотры

Piaget's Conservation Task and the Influence of Task Demands

Developmental Psychology

61.2K Просмотры

Children's Reliance on Artist Intentions When Identifying Pictures

Developmental Psychology

5.6K Просмотры

Measuring Children's Trust in Testimony

Developmental Psychology

6.3K Просмотры

Are You Smart or Hardworking? How Praise Influences Children's Motivation

Developmental Psychology

14.3K Просмотры

Memory Development: Demonstrating How Repeated Questioning Leads to False Memories

Developmental Psychology

10.9K Просмотры

Авторские права © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. Все права защищены