Method Article

缺氧人胎盘的小细胞外囊泡破坏小鼠血脑屏障

* 这些作者具有相同的贡献

摘要

提出了一种方案来评估从缺氧条件下培养的胎盘外植体中分离出的小 EV (sEV)(模拟先兆子痫的一个方面)是否会破坏未怀孕成年雌性小鼠的血脑屏障。

摘要

脑血管并发症,包括脑水肿、缺血性和出血性卒中,是先兆子痫导致孕产妇死亡的主要原因。这些脑血管并发症的潜在机制尚不清楚。然而,它们与胎盘功能障碍和血脑屏障 (BBB) 破坏有关。然而,这两个遥远器官之间的联系仍在确定中。越来越多的证据表明,胎盘将信号分子(包括细胞外囊泡)释放到母体循环中。细胞外囊泡根据其大小进行分类,小细胞外囊泡(直径小于 200 nm 的 sEV)在生理和病理条件下都被认为是关键信号转导颗粒。在先兆子痫中,母体循环中循环的sEV数量增加,其信号传导功能尚不清楚。在先兆子痫或暴露于缺氧的正常妊娠胎盘中释放的胎盘 sEV 会诱导脑内皮功能障碍和 BBB 破坏。在该方案中,我们评估了从缺氧条件下培养的胎盘外植体中分离的sEV(模拟先兆子痫的一个方面)是否会破坏 体内的BBB。

引言

大约70%的孕产妇死于先兆子痫,这是一种高血压妊娠综合征,其特征是胎盘过程受损,母亲全身性内皮功能障碍,严重时出现多器官衰竭1,2,与急性脑血管并发症有关3,4。大多数孕产妇死亡发生在低收入和中等收入国家5.然而,尽管与先兆子痫相关的脑血管并发症具有临床和流行病学相关性,但其潜在机制仍不清楚。

另一方面,细胞外囊泡 (EV)(直径 ~30-400 nm)是组织和器官之间细胞间通讯的重要介质,包括母胎相互作用6。除了外表面的蛋白质和脂质外,电动汽车还携带货物(蛋白质、RNA 和脂质)。EV 可分为 (1) 外泌体(直径 ~50-150 nm,也称为小型 EV (sEV))、(2) 中型/大型 EV 和 (3) 凋亡体,其大小、生物发生、含量和潜在的信号传导功能不同。EV 的组成由它们起源的细胞和疾病类型 7 决定。合体滋养层衍生的 EV 表达胎盘碱性磷酸酶 (PLAP)8,9,可检测妊娠期胎盘衍生的循环小 EV (PDsEV)。此外,PLAP 有助于辨别 PDsEV 货物的变化及其对子痫前期与血压正常妊娠的影响 10、11、12、13、14、15。

胎盘已被公认为先兆子痫病理生理学的必要组成部分16 或与该疾病相关的脑并发症 17,18,19。然而,这个远处的器官如何诱导脑循环的改变尚不清楚。由于 sEV 能够将生物活性成分从供体转移到受体细胞 6,20,21,因此越来越多的研究将胎盘 sEV 与母体内皮功能障碍的产生联系起来 21,22,23,24,包括脑内皮细胞25,26在患有先兆子痫的女性中。因此,脑内皮功能的损害可能导致血脑屏障 (BBB) 的破坏,血脑屏障是与子痫前期相关的脑血管并发症的关键组成部分 3,27。

然而,使用暴露于子痫前期女性血清的大鼠脑血管28 或暴露于子痫前期女性血浆的人脑内皮细胞29 的临床前研究结果报告说,循环因子诱导 BBB 的破坏。尽管有几种候选药物有可能损害先兆子痫期间母体循环中存在的血脑屏障,例如促炎细胞因子(即肿瘤坏死因子)18,28 或血管调节剂(即血管内皮生长因子 (VEGF))29,30,31 或氧化分子(如氧化脂蛋白 (oxo-LDL)32,33 等)水平升高34,它们都没有在胎盘和血脑屏障之间建立直接联系。最近,从缺氧胎盘中分离出的 sEV 显示出破坏未怀孕雌性小鼠 BBB 的能力25。由于胎盘 sEV 可能携带大多数列出的循环因子,具有破坏 BBB 的能力,因此 sEV 被认为是连接受损胎盘、成为有害循环因子的载体并破坏先兆子痫的 BBB 的合适候选者。

该协议使我们能够研究从在缺氧条件下培养的胎盘外植体中分离的sEV是否可以破坏未怀孕雌性小鼠的BBB,作为了解先兆子痫期间脑并发症的病理生理学的代表。

研究方案

该研究是按照《赫尔辛基宣言》中表达的原则进行的,并得到了各自伦理审查委员会的授权。如前所述,所有人类参与者在样本采集前都给予了知情同意25.此外,比奥比奥大学生物伦理学和生物安全委员会批准了该项目(Fondecyt 赠款1200250)。动物工作是根据实验35中使用动物的三个R的基本原则进行的,并根据美国国立卫生研究院发布的实验动物护理和使用指南的建议进行。动物被饲养在比奥比奥大学动物饲养室的适当环境中。在选择性剖宫产后 1 小时内从足月(妊娠 38 至 48 周)正常妊娠的母亲(28-31 岁)获得新鲜胎盘 (n = 4)。剖宫产是在智利奇兰的Herminda Martin临床医院进行的,正如之前报道的那样 25.为了应用体内模型,使用4-6个月大的雌性非妊娠小鼠(品系C57BLACK/6)。他们被分为三个实验组:(1)对照组(未经处理),(2)用常氧sEVs(sEVs-Nor)处理,(3)用缺氧培养胎盘(sEVs-Hyp)sEVs处理,用于评估体内BBB的破坏25。所有注射的溶液都是无菌的。此外,sEV的制备是在无菌条件下和II级生物安全罩下进行的,以避免污染。

1.胎盘培养外植体

- 要提取正常妊娠胎盘的外植体,请检查Miller等人发表的2005年36月的方法。

- 使用灭菌镊子小心地从人胎盘的基底板上去除凝块。提取小外植体以获得10g的最终组织提取。

- 确保从胎盘母体部分的四个象限中取出胎盘外植体。确保排除失活的组织和钙化区域。

- 要操纵胎盘组织,请在冰上、无菌条件下和生物安全柜内进行。

- 用大量(五体积的外植体)冷(4°C)磷酸盐缓冲溶液(PBS 1x,pH 7.4)洗涤外植体(至少三次),以去除尽可能多的血液。在洗涤之间在室温下离心(252× g10 分钟)。

- 将 10 g 洗涤的外植体重悬于补充有 2% 胎牛血清、100 IU/mL 青霉素和 100 μg/mL 链霉素的 20 mL 培养基中(参见 材料表)。

- 将悬浮液放入100mm培养皿中。将外植体在37°C的培养箱中用21%氧气和5%CO2放置2小时。

- 之后,在37°C(三次)下用1x PBS重新洗涤外植体。在洗涤之间在室温下离心(252× g10 分钟)。

- 此外,将组织重悬于先前耗尽纳米颗粒的 20 mL 培养基中。

注意:对于纳米颗粒耗尽,进行超速离心(120,000× g 在室温下18小时)和微滤(0.22μm过滤器)。 - 将重悬的外植体分成两个培养皿(100mm)。每个培养皿必须包括 10 mL 重悬外植体。

- 之后,将其中一个含有胎盘外植体的培养皿置于标准培养条件(37°C,8%氧气和5%CO2)中,同时将另一个培养皿置于含有1%O2的缺氧室中。

注:(可选)组织活力分析可以使用与其他地方描述的相同的组织提取和3-(4,5-二甲基噻唑-2-基)-2,5-二苯基四唑溴化物测定(MTT测定)进行,如其他地方37,38所述。使用在外植体匀浆中测量的总蛋白质浓度来标准化 MTT 值。 - 培养18小时后,将外植体的条件培养基收获到新的15mL管中。

注意:在此步骤中,条件培养基可以冷冻(-80°C)很长一段时间(数周)。

2. 胎盘来源的sEVs分离

- 按照先前发表的报告25,39,使用差速离心和微滤方案从条件培养基中分离sEV。

- 对收获的条件培养基进行顺序离心。离心的顺序步骤为(1)300× g10 分钟,(2)2000× g10 分钟,(3)10,000× g30 分钟,(4)120,000× g2 小时。在室温下进行离心。

- 在所有这些离心中,使用20-100μL移液管,仔细收集上清液并弃去沉淀。

- 完成后,将最后收集的上清液通过0.22μm过滤器(参见 材料表)。随后,在室温下以120,000× g 进行一次额外的离心18小时。

- 之后,弃去上清液,同时将沉淀(含有胎盘sEV)重悬于500μLPBS(pH 7.4)中,并再次通过0.22μm过滤器。最后,在室温下以120,000× g 进行最后一次离心3小时。

- 接下来,将沉淀(含有胎盘sEV)重悬于500μLPBS(pH 7.4,先前耗尽的sEV)中并通过0.22μm过滤器。

- 将样品标记为 sEVs-Normoxia (sEVs-Nor) 或 sEVs-Hypoxia (sEVs-Hyp) 的库存。

注意:准备 50-100 μL 分离的 sEV 等分试样以进行进一步实验。小型电动汽车可以在 -80 °C 下长时间(数月)储存。 - 如前所述,通过大小、计数和 sEVs 蛋白标记物表征胎盘 sEV25。sEV 的理想平均粒径为 50-150 nm。

注意:sEV 表征包括对 CD63、Tsg101、Alix 和 HSP70 的阳性检测(即表征富集于外泌体的 sEV 群体)。此外,使用PLAP作为胎盘起源的标志物25。 - 按照制造商的说明,使用 BCA 蛋白检测试剂盒测量 sEVs 溶液中的蛋白质总量(参见 材料表)。

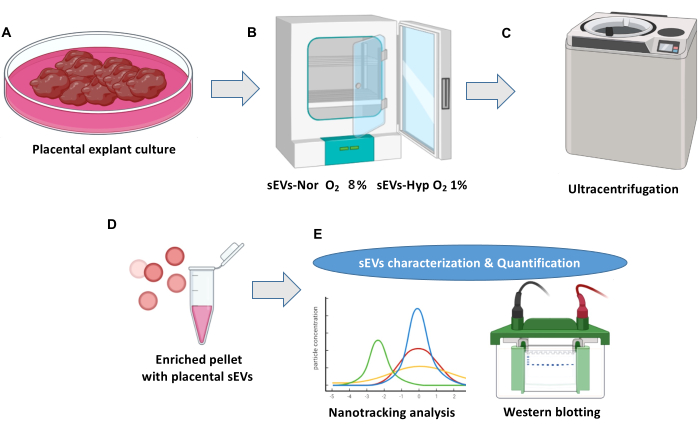

注: 图1 显示了胎盘外植体培养和细胞外囊泡分离的概述。

3.小鼠注射

- 在异氟烷分布为5%的麻醉诱导室中麻醉动物(见 材料表)。 通过 捏脚趾来验证麻醉程度。

- ~40秒后,使用面罩将小鼠放入麻醉系统中,并保持2%异氟烷的麻醉水平。

- 接下来,将动物放置在室温为28°C的加热平台上(参见 材料表)。 用人工泪液润滑眼睛。

- 注射前,用磷酸盐缓冲液(pH,7.4)稀释胎盘sEV(200μg总蛋白),直至达到70μL的最终体积。

- 使用70%乙醇和棉签对注射区域进行消毒。确保使用带有 30 G 针头的胰岛素注射器注射 sEVs 溶液。

注意: 注射器可以放置在加热平台上 5 分钟以获得生理温度。 - 然后,将溶液注射到颈外静脉中。此步骤需要特殊培训。

注意:该过程必须谨慎进行,缓慢缩回针头并轻轻吸气以发现血液反流的证据。 - 注射后,用干棉签轻轻按压注射区域~15秒。之后,将动物放回各自的笼子。

- 确保评估意识和行为 15 分钟。意识成就的一个指标是动物总运动活动的恢复。

注意: 确保在动物笼子里保持温暖的温度。

4. 快速小鼠昏迷和行为量表(RMCBS)

- 使用 RMCBS 评估动物的神经和健康参数40.

注意:RMCBS 允许快速评估(~ 3 分钟),由于操作员干预,动物压力最小。RMCBS 有 10 个参数(每个分数为 0-2)。 - 在注射后0小时(注射sEV之前)和注射后3小时,6小时,12小时和24小时使用RMCBS量表评估小鼠的健康状况。

注意:对claudin-5(sEVs注射后6小时)和Evan蓝色外渗(sEVs注射后24小时)进行分析,以评估BBB的破坏(图2)。

5. 埃文的蓝色外渗分析

- 在胎盘sEVs注射(24小时)后,按照步骤3.1中的描述麻醉小鼠。

- 制备Evan's Blue溶液(2%,在磷酸盐缓冲溶液中稀释,1x)(参见 材料表)。

- 使用轨道后通路25,以 2 mL/kg 的速度注入 Evan 的 Blue 溶液。

- 让Evan的蓝色溶液在麻醉维持下循环20分钟。

- 接下来,按照先前描述的方案41 用盐水溶液(~3 mL,0.9%,w/v)进行心内灌注,以从循环中去除 Evan 的蓝色染料。此步骤是强制性的。

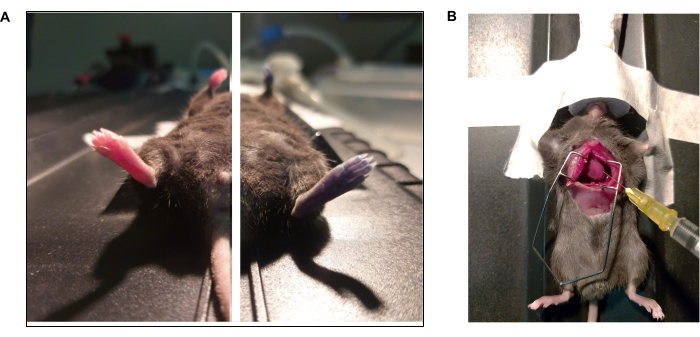

注意:对于此程序,将麻醉增加到 5% 并验证深度麻醉平面(即呼吸频率急剧降低)。 - 通过内侧开胸术暴露心脏41(图3)。

- 之后,用心内输注多聚甲醛溶液(PBS中的4%,v / v)固定整个动物。

注意: 检查尾部的刚度以监控适当的固定。 - 此外,一旦固定完成,小心地提取大脑,称重并拍照41.用整个大脑靠近尺子拍照 42.

- 接下来,将大脑放入脑鼠切片器中(参见 材料表)。

- 将大脑解剖成九个部分,鹤尾,包括小脑(每个部分100μm)。

- 解剖后,在立体变焦显微镜中可视化并捕获脑切片的图像(参见 材料表)。

- 使用捕获的图像,使用ImageJ软件量化Evan的蓝色外渗(参见 材料表)。

注意:要分析Evan蓝色染料的存在,请使用脑切片的阳性对照(来自注射染料但未进行心内灌注的动物对照动物)设置Evan的蓝色值。在蓝色通道的强度直方图中,从阳性对照获得的 Evan 蓝色值通常在 75 到 110 之间(图 4)。 - 确保由各自的实验组盲目分析脑图像,以避免观察者偏见。或者,通过脑均质化和光谱43 来量化 Evan 的蓝色外渗。

注意:在单独的实验中,使用从注射sEVs的小鼠(6小时)中新鲜分离的大脑,分析claudin 5(CLND-5)的蛋白质水平(参见 材料表),这是与BBB44 的紧密性有关的临界紧密连接(图5)。

结果

该方案评估了来自在缺氧中培养的胎盘的sEV破坏非妊娠小鼠BBB的能力。这种方法可以更好地理解正常和病理条件下胎盘和大脑之间的潜在联系。特别是,该方法可以构成分析胎盘sEV参与先兆子痫脑并发症发作的代理。

与注射sEVs-Nor的小鼠相反,注射sEVs-Hyp的小鼠在24小时内显示神经评分逐渐下降(表1),这表明sEVs-Hyp损害大脑功能的能力。

此外,注射sEVs-Hyp组的小鼠脑比从注射sEVs-Nor的小鼠或对照小鼠中分离的小鼠脑具有更高的鲜重(分别为0.51±0.008;0.46±0.008;0.47±0.01g),这可能构成脑水肿的大体指标45。

与这一发现兼容,该协议允许人们将Evan的蓝色外渗识别为BBB破坏的指标。在这方面,注射sEVs-Hyp的小鼠的大脑比sEVs-Nor组的大脑具有更高的Evan蓝色外渗(图5A)。

尽管未使用该方案分析sEVs-Hyp诱导的BBB破坏的潜在机制,但结果还表明,注射sEVs-Hyp的小鼠在BBB受影响最大的区域(即后部区域)显示CLND-5的蛋白质含量减少(图5B)。因此,sEVs-hyp 可能会损害这种关键内皮紧密连接蛋白的功能表达。

图1:胎盘外植体培养和细胞外囊泡分离方案。 (A)正常胎盘外植体培养物。(B) 外植体分布在胎盘小细胞外囊泡 (sEV) 生物发生的两种条件下。常氧(sEVs-Nor,8%O2)或缺氧(sEVs-Hyp,1%O2)18小时。 (C)收获,过滤和离心条件培养基以消除细胞碎片。(D) sEV通过超速离心分离。(E) 使用纳米跟踪分析和蛋白质印迹法表征sEV。 请点击这里查看此图的较大版本.

图2:血脑屏障破坏方案的 体内 评估。 使用4-6个月大的非怀孕C57BL6 / J小鼠。(A)通过颈外静脉,动物接受从常氧(sEVs-Nor,8%O2)或缺氧(sEVs-Hyp,1%O2)胎盘培养物中分离的sEV(200μg总蛋白)。注射后0-24小时监测RMCBS。(B)注射sEVs后6小时,提取大脑并切成九个部分进行蛋白质提取。Claudin 5 (CLDN5) 在这九个部分的匀浆中进行分析。(C) 在9个节段中的每一个节段进行眼眶后穿刺注射后分析Evan的蓝色外渗分析(sEVs注射后24 h)。 请点击这里查看此图的较大版本.

图 3:Evan 蓝色染料和心内灌注方案的照片纪录片。 (A) 小鼠通过眼眶后注射接受 Evan 的蓝色。(左)注射埃文蓝之前和(右)注射(15 秒)后的动物。(B) 开胸术进行磷酸盐缓冲溶液 (1x PBS) 和多聚甲醛 (4% PFA) 的心内灌注。左心室用针尖指向左心室。 请点击这里查看此图的较大版本.

图 4:注射 sEV 后 Evan 蓝色外渗的分析。 (A) 显示 Evan 蓝色外渗的全脑代表性图像。虚线代表从整个大脑中获得的九个部分。(B)使用脑小鼠切片机解剖大脑。(C)sEVs注射后24小时脑切片的代表性图像。对照 (CTL)、常氧 (sEVs-Nor) 或缺氧条件下的胎盘 (sEVs-Hyp)。比例尺 = 0.4 厘米。 (D) 使用 ImageJ 对脑切片进行数字勾勒。(E) 蓝色通道中的直方图。介于 75-110 之间的值与 Evan 的蓝色外渗有关。 请点击这里查看此图的较大版本.

图 5:注射从胎盘外植体分离的 sEV 的小鼠中的 Evan 蓝色外渗和 claudin-5 水平。 (A) 考虑全脑切片的 Evan 蓝 (EB) 外渗百分比。对照(CTL,蓝色),常氧(sEVs-Nor,红色)或缺氧条件下的胎盘(sEVs-Hyp,绿色)。(B)从三个实验组获得九个脑切片中claudin 5(CLDN5)的相对水平。β-肌动蛋白用作负载控制。值是四分位距±平均值。每个点代表一个单独的实验对象。*p < 0.05,**p < 0.005。p < 0.0001。p < 0.001;方差分析检验,然后是 Bonferroni 后检验。 请点击这里查看此图的较大版本.

| 时间 (h) | 控制 | sEVs-常氧 | sEVs-缺氧 | 方差分析 |

| 0 | 18.75 ± 0.250 | 18.5 ± 0.288 | 18.75 ± 0.250 | ns |

| 3 | 18.5 ± 0.866 | 17 ± 0.707 | 13.25 ± 1.750*α | 0.006 |

| 6 | 19.25 ± 0.750 | 17 ± 0.577 | 11.75 ± 1.250*α | 0.002 |

| 12 | 18.5 ± 0.645 | 16.75 ± 1.109 | 13 ± 0.816*α | 0.001 |

| 24 | 19.5 ± 0.288 | 17.75 ± 0.250 | 10.25 ± 0.853*α | <0.0001 |

| *p < 0.01 与对照组相比。αp < 0.01 vs sEVs-常氧 | ||||

表 1:sEVs 注射后 24 小时后的快速小鼠昏迷和行为量表 (RMCBS)。 该分数表示为平均± SEM。 动物的分数最接近 20 是标准的,而分数越低,中枢神经系统功能障碍越高。

讨论

这项研究揭示了从缺氧条件下培养的胎盘外植体中分离出的 sEV 对啮齿动物血脑屏障破坏的潜在危害的新见解。病理机制涉及后脑区25中CLND-5的减少。

先前的研究表明,使用体外模型46,47,来自先兆子痫患者的血浆 sEV 会诱导各种器官的内皮功能障碍。这项研究特别仔细检查了血脑屏障,为从缺氧培养的胎盘中分离出的sEV提供了新的视角,这破坏了这一重要屏障。这些发现引入了一个新的研究领域,其中sEVs可以在正常和病理情况下(如先兆子痫)作为胎盘和大脑之间的沟通渠道。

所提出的协议很简单,但有几个关键步骤值得一提。该协议需要在分娩后 1 小时内获得新鲜胎盘。我们还建议不要将培养期延长到24小时以上,以防止组织降解。该协议减轻了小鼠胎盘产生的sEV的潜在污染。对埃文蓝色外渗的数字分析是耗时的。此外,埃文的蓝色染色在脑切片后不那么明显。因此,建议使用阳性对照进行识别蓝色范围的初始设置。也可以采用阴性对照,例如未接受埃文蓝色注射的小鼠的大脑。对实验组进行盲分析对于避免潜在的观察者偏见至关重要。

在此协议期间可能会出现一些挑战。一个显着的局限性在于源自人类胎盘和注射小鼠的生物变异性。为了确保 Evan 蓝色外渗实验的可重复性,建议建立从人胎盘中分离的 sEV 剂量。我们选择了200μg总蛋白的剂量;然而,该数量可能会根据囊泡纯度、颈静脉注射的功效、Evan 的蓝色给药、其从循环系统中的清除率以及考虑其内容的 sEV 的生物学影响而波动。

来自人类胎盘的sEVs可以破坏血脑屏障的细胞机制需要额外的实验。然而,这种方法具有相关性,暗示了胎盘和大脑之间的潜在交流,值得进一步探索。因此,鼓励未来的研究,专注于sEV及其与血脑屏障的相互作用,以及它们的货物对神经元组织的影响。血脑屏障损伤是否会导致母体大脑的持久后果,值得进一步检查。

披露声明

作者没有任何利益冲突需要声明。

致谢

作者要感谢 GRIVAS Health 的研究人员的宝贵意见。此外,妇产科的助产士和临床工作人员属于智利奇兰医院。由 Fondecyt Regular 1200250 创立。

材料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Adult mice brain slecer matrice 3D printed | Open access file | Adult mice | Adult mice brain slicer. Printed in PLA filament. |

| Anti β-Actin primary antibody | Sigma-Aldrich | Clon AC-74 | Antibody for loading control (Western blot) |

| Anti-Claudin5 primary antibody | Santa cruz Biotechnology | sc-374221 | Primary antibody for tight junction protein CLDN5 of mice BBB (Western blot) |

| BCA protein kit | Thermo Scientific | 23225 | Kit for measuring protein concentration |

| Culture media #200 500 mL | Thermo Fisher Scientific | m200500 | Culture media for placental explants |

| D180 CO2 incubator | RWD Life science | D180 | Standard incubator to estabilize explants and culture sEVs-Nor |

| Evans blue dye > 75% 10 g | Sigma-Aldrich | E2129.10G | Dye to analize blood brain barrier disruption IN VIVO |

| Fetal bovine serum 500 mL | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 16000044 | Additive growth factor for culture media 200 |

| Himac Ultracentrifuge CP100NX | Himac eppendorf group | 5720410101 | Ultracentrifuge for condicioned media > 1,20,000 x g |

| ImageJ software | NIH | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/download.html | |

| Isoflurane x 100 mL | USP Baxter | 212-094 | Volatile inhalated anaesthesia agent for mice |

| Kit CellTiter 96 Non-radioactive | Promega | 0000105232 | In vitro assay for placental explants viability |

| Mouse IgG Secondary antibody | Thermo Fisher Scientific | MO 63103 | Secondary antibody for CLDN5 (western blot) |

| NanoSight NS300 | Malvern Panalytical | 90278090 | Nanotracking analysis of particles from placental explants condicioned media |

| Paraformaldehide E 97% solution 500 mL | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A11313.22 | Fixative solution for brain tissue slices and intracardial perfusion (once diluted) |

| PBS 1 X pH 7.4 500 mL | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 10010023 | Wash solution for placenta explants |

| Peniciline-streptomicine 100x 20 mL | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 10378016 | Antiobiotics for placental explants culture media |

| ProOX C21 Cytocentric O2 and CO2 Subchamber Controller | BioSpherix | SCR_021131 | CO2 regulator to induce Hypoxia in sealed chamber for sEVs-Hyp |

| Sodium Thiopental 1 g | Chemie | 7061 | humanitarian euthanasia agent |

| Somnosuite low flow anesthesia system | Kent Scientifics | SS-01 | Isoflurane vaporizer for small rodents |

| Surgical Warming platform | Kent Scientifics | A41166 | Warming platform for mainteinance anesthesia in mice |

| Syringe Filters, Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), Hydrophobic, 0.22 µm, Sterile, 25 mm | Southern labware | 10026 | Filtration of condicioned media harvested from placental explants |

| Tabletop High-Speed Micro Centrifuges HITACHI himac CT15E/CT15RE | Hitachi medical systems | 6020 | Serial centrifugations of condicioned media < 1,20, 000 x g |

| Trinocular stereomicroscope transmided and reflective light 10x-160x | Center Medical | 2597 | Stereomicroscope to register brain slices |

参考文献

- Lisonkova, S., Joseph, K. S. Incidence of preeclampsia: risk factors and outcomes associated with early- versus late-onset disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 209 (544), 544.e1-544.e12 (2013).

- Sibai, B., Dekker, G., Kupferminc, M. Preeclampsia. Lancet. 365 (9461), 785-799 (2005).

- Hammer, E. S., Cipolla, M. J. Cerebrovascular dysfunction in preeclamptic pregnancies. Curr Hypertens Rep. 17 (8), 64 (2015).

- Okanloma, K. A., Moodley, J. Neurological complications associated with the preeclampsia/eclampsia syndrome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 71, 223-225 (2000).

- Frias, A. E., Belfort, M. A. Post magpie: how should we be managing severe preeclampsia. Curr Opin Gynecol Obstet. 15 (6), 489-495 (2003).

- Familari, M., Cronqvist, T., Masoumi, Z., Hansson, S. R. Placenta-derived extracellular vesicles: Their cargo and possible functions. Reprod Fertil Dev. 29 (3), 433-447 (2017).

- Montoro-Garcia, S., Shantsila, E., Marin, F., Blann, A., Lip, G. Y. Circulating microparticles: new insights into the biochemical basis of microparticle release and activity. Basic Res Cardiol. 106, 911-923 (2011).

- Germain, S. J., Sacks, G. P., Sooranna, S. R., Sargent, I. L., Redman, C. W. Systemic inflammatory priming in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia: the role of circulating syncytiotrophoblast microparticles. J Immunol. 178 (9), 5949-5956 (2007).

- Tannetta, D., Masliukaite, I., Vatish, M., Redman, C., Sargent, I. Update of syncytiotrophoblast derived extracellular vesicles in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. J Reprod Immunol. 119, 98-106 (2017).

- Collett, G. P., Redman, C. W., Sargent, I. L., Vatish, M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress stimulates the release of extracellular vesicles carrying danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecules. Oncotarget. 9 (6), 6707-6717 (2018).

- Cooke, W. R., et al. Maternal circulating syncytiotrophoblast-derived extracellular vesicles contain biologically active 5'-tRNA halves. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 518 (1), 107-113 (2019).

- Gill, M., et al. Placental syncytiotrophoblast-derived extracellular vesicles carry active nep (neprilysin) and are increased in preeclampsia. Hypertension. 73 (5), 1112-1119 (2019).

- Kandzija, N., et al. Placental extracellular vesicles express active dipeptidyl peptidase IV; levels are increased in gestational diabetes mellitus. J Extracell Vesicles. 8 (1), 1617000 (2019).

- Motta-Mejia, C., et al. Placental vesicles carry active endothelial nitric oxide synthase and their activity is reduced in preeclampsia. Hypertension. 70 (2), 372-381 (2017).

- Sammar, M., et al. Reduced placental protein 13 (PP13) in placental derived syncytiotrophoblast extracellular vesicles in preeclampsia - A novel tool to study the impaired cargo transmission of the placenta to the maternal organs. Placenta. 66, 17-25 (2018).

- Burton, G. J., Woods, A. W., Jauniaux, E., Kingdom, J. C. Rheological and physiological consequences of conversion of the maternal spiral arteries for uteroplacental blood flow during human pregnancy. Placenta. 30 (6), 473-482 (2009).

- Warrington, J. P., et al. Placental ischemia in pregnant rats impairs cerebral blood flow autoregulation and increases blood-brain barrier permeability. Physiological Reports. 2 (8), e12134-e12134 (2014).

- Warrington, J. P., Drummond, H. A., Granger, J. P., Ryan, M. J. Placental Ischemia-induced increases in brain water content and cerebrovascular permeability: Role of TNFα. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 309 (11), R1425-R1431 (2015).

- Johnson, A. C., et al. Magnesium sulfate treatment reverses seizure susceptibility and decreases neuroinflammation in a rat model of severe preeclampsia. PLoS ONE. 9 (11), e113670 (2014).

- Escudero, C. A., et al. Role of extracellular vesicles and microRNAs on dysfunctional angiogenesis during preeclamptic pregnancies. Front Physiol. 7, 1-17 (2016).

- Salomon, C., et al. Placental exosomes as early biomarker of preeclampsia: Potential role of exosomalmicrornas across gestation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 102 (9), 3182-3194 (2017).

- Knight, M., Redman, C. W., Linton, E. A., Sargent, I. L. Shedding of syncytiotrophoblast microvilli into the maternal circulation in pre-eclamptic pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 105 (6), 632-640 (1998).

- Gilani, S. I., Weissgerber, T. L., Garovic, V. D., Jayachandran, M. Preeclampsia and extracellular vesicles. Curr Hypertens Rep. 18 (9), 68 (2016).

- Dutta, S., et al. Hypoxia-induced small extracellular vesicle proteins regulate proinflammatory cytokines and systemic blood pressure in pregnant rats. Clin Sci (Lond). 134 (6), 593-607 (2020).

- Leon, J., et al. Disruption of the blood-brain barrier by extracellular vesicles from preeclampsia plasma and hypoxic placentae: attenuation by magnesium sulfate. Hypertension. 78 (5), 1423-1433 (2021).

- Han, C., et al. Placenta-derived extracellular vesicles induce preeclampsia in mouse models. Haematologica. 105 (6), 1686-1694 (2020).

- Amburgey, O. A., Chapman, A. C., May, V., Bernstein, I. M., Cipolla, M. J. Plasma from preeclamptic women increases blood-brain barrier permeability: role of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. Hypertension. 56 (5), 1003-1008 (2010).

- Cipolla, M. J., et al. Pregnant serum induces neuroinflammation and seizure activity via TNFalpha. Exp Neurol. 234 (2), 398-404 (2012).

- Bergman, L., et al. Preeclampsia and increased permeability over the blood brain barrier - a role of vascular endothelial growth receptor 2. Am J Hypertens. 34 (1), 73-81 (2021).

- Torres-Vergara, P., et al. Dysregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 phosphorylation is associated with disruption of the blood-brain barrier and brain endothelial cell apoptosis induced by plasma from women with preeclampsia. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1868 (9), 166451 (2022).

- Schreurs, M. P., Houston, E. M., May, V., Cipolla, M. J. The adaptation of the blood-brain barrier to vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor during pregnancy. FASEB J. 26 (1), 355-362 (2012).

- Schreurs, M. P., Cipolla, M. J. Cerebrovascular dysfunction and blood-brain barrier permeability induced by oxidized LDL are prevented by apocynin and magnesium sulfate in female rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 63 (1), 33-39 (2014).

- Schreurs, M. P. H., et al. Increased oxidized low-density lipoprotein causes blood-brain barrier disruption in early-onset preeclampsia through LOX-1. FASEB J. 27 (3), 1254-1263 (2013).

- Escudero, C., et al. Brain vascular dysfunction in mothers and their children exposed to preeclampsia. Hypertension. 80 (2), 242-256 (2023).

- Russell, W. M. S., Burch, R. L. The principles of humane experimental technique. Universities Federation of Animal Welfare. , (1959).

- Miller, R. K., et al. Human placental explants in culture: approaches and assessments. Placenta. 26 (6), 439-448 (2005).

- Troncoso, F. A. J., Herlitz, K., Ruiz, F., Bertoglia, P., Escudero, C. Elevated pro-angiogenic phenotype in feto-placental tissue from gestational diabetes mellitus. Placenta. 36 (4), 2 (2015).

- Zhang, H. C., et al. Microvesicles derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells stimulated by hypoxia promote angiogenesis both in vitro and in vivo. Stem Cells Dev. 21 (18), 3289-3297 (2012).

- Thery, C., Amigorena, S., Raposo, G., Clayton, A. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. Chapter 3 (Unit 3), 22 (2006).

- Carroll, R. W., et al. A rapid murine coma and behavior scale for quantitative assessment of murine cerebral malaria. PLoS One. 5 (10), e13124 (2010).

- Wu, J., et al. Transcardiac perfusion of the mouse for brain tissue dissection and fixation. Bio Protoc. 11 (5), e3988 (2021).

- Walchli, T., et al. Quantitative assessment of angiogenesis, perfused blood vessels and endothelial tip cells in the postnatal mouse brain. Nat Protoc. 10 (1), 53-74 (2015).

- Wang, H. L., Lai, T. W. Optimization of Evans blue quantitation in limited rat tissue samples. Sci Rep. 4, 6588 (2014).

- Morita, K., Sasaki, H., Furuse, M., Tsukita, S. Endothelial claudin: claudin-5/TMVCF constitutes tight junction strands in endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 147 (1), 185-194 (1999).

- Lara, E., et al. Abnormal cerebral microvascular perfusion and reactivity in female offspring of reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) mice model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 42 (12), 2318-2332 (2022).

- Chang, X., et al. Exosomes from women with preeclampsia induced vascular dysfunction by delivering sflt (soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase)-1 and seng (soluble endoglin) to endothelial cells. Hypertension. 72, 1381-1390 (2018).

- Smarason, A. K., Sargent, I. L., Starkey, P. M., Redman, C. W. The effect of placental syncytiotrophoblast microvillous membranes from normal and pre-eclamptic women on the growth of endothelial cells in vitro. BJOG. 100 (10), 943-949 (1993).

转载和许可

请求许可使用此 JoVE 文章的文本或图形

请求许可探索更多文章

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

版权所属 © 2025 MyJoVE 公司版权所有,本公司不涉及任何医疗业务和医疗服务。