Method Article

침연 (macerated) 조직의 전자 현미경을 스캔하면 세포 외 매트릭스를 시각화하기

요약

Shown here is a method for visualizing extracellular matrix ultrastructure in decellularized cardiac tissues.

초록

Fibrosis is a component of all forms of heart disease regardless of etiology, and while much progress has been made in the field of cardiac matrix biology, there are still major gaps related to how the matrix is formed, how physiological and pathological remodeling differ, and most importantly how matrix dynamics might be manipulated to promote healing and inhibit fibrosis. There is currently no treatment option for controlling, preventing, or reversing cardiac fibrosis. Part of the reason is likely the sheer complexity of cardiac scar formation, such as occurs after myocardial infarction to immediately replace dead or dying cardiomyocytes. The extracellular matrix itself participates in remodeling by activating resident cells and also by helping to guide infiltrating cells to the defunct lesion. The matrix is also a storage locker of sorts for matricellular proteins that are crucial to normal matrix turnover, as well as fibrotic signaling. The matrix has additionally been demonstrated to play an electromechanical role in cardiac tissue. Most techniques for assessing fibrosis are not qualitative in nature, but rather provide quantitative results that are useful for comparing two groups but that do not provide information related to the underlying matrix structure. Highlighted here is a technique for visualizing cardiac matrix ultrastructure. Scanning electron microscopy of decellularized heart tissue reveals striking differences in structure that might otherwise be missed using traditional quantitative research methods.

서문

Fibrosis disrupts the normal myocardial collagen network, which is critical for normal mechanistic functions of cardiomyocytes 1,2 as well as for inter-cellular communication, intracellular signaling, and cell survival 3. The development of fibrosis is a major determinant of cardiac function, and fibrotic remodeling of the cardiac interstitium arising from a variety of etiologies leads to increased left ventricular stiffness and diastolic dysfunction 4. Myocardial fibrosis may also lead to arrhythmias, and whether the progression of fibrotic remodeling is a general or local phenomenon, it is highly associated with a poor prognosis in patients with ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy 5. Likewise, the absence of myocardial fibrosis is a strong predictor of ventricular functional recovery and long-term survival 6.

The hallmark of fibrosis is the deposition of excess collagen, which has the tensile strength of steel 7 and can adversely affect cardiomyocyte function on multiple levels. Mechanical forces resulting from an excessively collagenous matrix can lead to cardiomyocyte atrophy 8,9, passive tissue stiffness 10, tonic contraction-induced myocardial stiffness 11-13, and reduced delivery of oxygen to the remaining population of cardiomyocytes. Gap junction coupling of cardiomyocytes and myoFbs can also compromise the heart's electrical characteristics, creating a greater risk for the development of arrhythmias 14-16. Perivascular fibrosis alters vasomotor reactivity of intramural coronary arteries and arterioles 17 and contributes to luminal narrowing that reduces the supply of oxygen and thus the survival of cardiomyocytes 17-22. Pathogenic fibrotic and electrical remodeling, emanating from an initial site of ischemic injury or energy imbalance, inevitably progresses to heart failure.

Cardiomyocyte necrosis initiates the fibrotic response, and subsequent adverse fibrotic remodeling can occur irrespective of etiology. Finding a way to control cardiac fibrosis would be clinically beneficial for the treatment of ischemic and idiopathic cardiomyopathies, hypertensive heart disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease and dystrophinopathies 23-42. Regardless of how the fibrotic disease process begins, soluble, profibrotic factors can cross the interstitial space and provoke activation of interstitial and adventitial fibroblasts at sites remote to the initial fibrotic scar, creating a cascade effect that ultimately leads to heart failure. The optimum scenario would be to exploit the fibrillogenic process using a targeted therapeutic that can be applied during the compensative hypertrophic stage of cardiomyopathy before it progresses to systolic pump failure, diastolic heart failure, or other end-stage outcomes. The ultimate goal would be to reverse fibrosis so that dead cardiomyocytes can be replaced and heart function restored completely.

The importance of the matrix is widely understood, yet methods to study the matrix are limited mainly to quantitative measurements of major structural components, particularly collagen, and relative levels of different matrix and matricellular proteins. This protocol highlights a rarely used technique that is useful for assessing qualitative differences in the cardiac matrix. This technique has been recently used to compare and contrast fundamental differences in heart matrices from different etiologies of heart disease (in human explants), to examine hearts from post-infarcted pigs treated with the glial growth factor (GGF) isoform of neuregulin-1β, relative to untreated animals 43, and to probe for differences in the matrices of cardiac tissues from mdx mice (a commonly used animal model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy) at different ages and compared to wild-type controls. This technique was first introduced by Drs. Caulfield and Borg in 1979 44, but few studies have since employed this powerful technique 45-47, re-introduced here with only slight modification. This methodology is a valuable research tool, because it provides qualitative information about extracellular matrix ultrastructure that might otherwise be overlooked when simply measuring matrix component content and/or level of fibrosis.

프로토콜

윤리 문 : 동물 처리를위한 프로토콜 밴더빌트 기관 동물 관리 및 사용위원회 (IACUC에 의해 승인 된, AAALAC-국제 표준에 따라 수 M / 1백17분의 10 (돼지) 및 M / 219분의 10 (마우스) 및 실시를 프로토콜. 뱅크 인간의 심장 조직의 사용법은 밴더빌트 대학 의료 센터 IRB (프로토콜 번호 100887)에 의해 승인되었다.

1. 시료 채취 및 보관

- 0.1 M 인산 완충액 (PB) 용액에 신선한 4 % 글루 타르 알데히드를 확인합니다.

주의 : 글루 타르 알데히드는 독성 흄 후드에서 작업용 장갑을 착용하십시오.- 1,000 ml의 DH 2 O 21.8 g이 나 HPO 4, 6.4 g의의 NaH 2 PO 4. 양자 satis (품질 평가 점수)를 사용하여 PB, 산도 7.4의 0.2 M 원액을

- PB 원액 2.5 mL 및 2.1 ml의 DH 2 O.에 50 % 글루 타르 알데히드 400 μl를 추가

- 덩어리를 담가 (더 큰 이상이 C 없다4 %의 글루 타르 알데히드 용액에 조직의 평방 미터). 주 : 작은 조각들도 사용될 수 있지만 쉽게 프로토콜 이후의 단계를 용이하게하기 위해 눈에 의해 가시화 될 수있는 충분한 크기 (NO 미만 5mm 2)이어야한다.

- 4 ℃에서 무한히 저장 후, 실온에서 1 시간 동안 인큐베이션.

심장 조직의 2. 탈세 포화

- 10g의 수산화 나트륨 펠렛 / 100 ㎖ DH 2 O.을 사용 신선한 10 % NaOH 수용액을

주의 : 수산화 나트륨 용액은 부식성 및 알칼리 화상을 입을 수, 장갑을 착용하십시오. - DH 2 O.에서 조직을 씻어

- 6 실온에서 10 % NaOH 용액에 품어 - 십일 (까지에 붉은 갈색의 조직 변경 오프 흰색 또는 흰색).

- 조직이 투명하게 될 때까지 DH 2 O에 씻어.

- 실온에서 4 시간 동안 1 % 탄닌산의 조직을 담근다. 4 ML의 DH 2 O. 당 1 ml의 5 % 원액을 사용하여

주의 : 타닌산강한 자극은, 장갑을 착용하십시오. - 밤새 DH 2 O에 씻어.

3. Osmication과 (안전을위한 연기 후드에서) 심장 조직의 탈수

- 21.4 g 나트륨 cacodylate, 10.0 g의 염화 칼슘 및 450 ml의 2 O. DH를 사용 cacodylate 나트륨 완충액, 0.2 M 스톡 용액을 제조 7.4의 pH를 조정하기 위해 필요에 따라 혼합 한 후 염산. Qs를 500 ml의 DH (2)와 O.

주의 : 나트륨 cacodylate 염산은 독성 흄 후드에서 작업용 장갑을 착용하십시오. - 50 ㎖ DH 2 O. 1g의 산화 오스뮴 결정을 용해시켜 안전 흄 후드에서 산화 오스뮴의 2 % 수용액 스톡 용액을 제조

주의 : 오스뮴 화이이 심한 흡입의 위험이 있습니다; 점막이나 안구의 증기 고정이 가능, 따라서 만 장갑과 흄 후드에서 처리합니다. 스플래시 가드를 권장합니다. - DH와 1 : 원액 1을 혼합 (0.1 M 나트륨 cacodylate 버퍼에 조직을 씻어 2 O) 5 회에 분 (또는 부드러운 교반 용).

- 세 개의 버퍼 린스 총 두 번 이전 단계를 반복합니다.

- 회에 1 시간 동안 0.1 M 나트륨 cacodylate 버퍼 (1 재고 나트륨 cacodylate 및 주식 산화 오스뮴 (1) 혼합)에 1 % 산화 오스뮴의 조직을 담가.

- 5 분, 회 전자의 각 0.1 M 나트륨 cacodylate 완충액을 3 회 조직을 씻어.

- 회에 15 분간 각각의 에탄올 농도를 증가 (30 %, 50 %, 75 %, 85 %, 95 %, 마지막으로 100 %)를 사용하여 조직을 헹군다.

SEM 4. 단면 표면 준비

- 또한, 100 %의 에탄올을 함유하는 얕은 페트리 접시에 100 % 에탄올에 조직을 옮긴다.

- 양쪽의 플랫 시험편 위에 정삼각형의 양쪽을 형성하기 위해 서로 절단 날 크로스와 접촉되도록 두 개의 매우 날카로운 면도날을 잡아. 이를 달성하기 위해, 샘플의 오른쪽 측면에 하나의 블레이드를 배치 왼손 사용컷 좌측. 동시에, 지금까지 샘플 조각 우측의 좌측의 2 블레이드를 배치 오른손을 사용한다. 따라서, 상기 블레이드는 단일 부드러운 컷을 반대 방향에서 서로에 대해 활주한다.

- 시험편을 손상시키지 않고 바람직하게는 가능한 한 큰 면적을 노광, 왜곡을 최소화 또는 강제 찢어와 시험편의 매우 깨끗한 컷을 만들기 위해 서로 플랫 블레이드 양측 활주.

- 주사 전자 현미경의 검사를 위해 가장 깨끗한 가능한 단면 표면을 노출 각 시료에 대해 반복합니다.

5. 임계점 건조 (CPD) 심장 조직의

- 조직이 항상 100 % 에탄올에 남아 있도록, 임계점 건조기 (CPD)의 샘플 홀더에 조직을 전송 주걱이나 핀셋을 사용한다. 홀더는 에탄올 및 전송이 몇 초 이상 더 이상 공기에 노출 된 조직으로 달성되도록 침지되어 있는지 확인합니다.

- 우리 당 CPD를 작동ER 서 액체 이산화탄소와 에탄올을 대체 사이클 충전 및 퍼지-3을 작성한다.

- 샘플의 임계점 건조를 달성하고 CO 2의 제어 배기와 대기압에 반환하기 위해 사용 설명서에 따라 CPD를 운영하고 있습니다.

SEM에 대한 심장 조직 표본 6. 장착

- 알루미늄 스터브의 상면에 탄소 접착제 탭을 접착하여, 각 시험편에 대한 SEM 샘플 스텁을 준비한다.

- 실체 현미경의 도움으로 조심 (멀리 보이는 탭)에서 위를 향 관심 단면 표면과 접착 탭 시험편을 부착 한 최대한 가까운 샘플 스텁 표면의 평면과 평행하도록. 조사 또는 관심의 표면을 만지지 마십시오.

- 페인트 응용 프로그램에 대한 이상적인 테이퍼 브러쉬를 달성하기 위해 나무 주걱 스틱을 휴식. 스터브에 부착을 향상시키기 위해, 기지국 및 시험편의 측면에은이나 카본 페인트를 적용한다.

- 접지 관심 표면으로부터 충전 경로를 제공하기 위해, 관심의 표면의 가장자리까지 칠은 또는 탄소의 매우 얇은 라인을 확장한다.

- 접지에 따라서 금속 스터브 탄소 탭 표면으로부터 도전로를 제공하는 탄소 탭 둘레은이나 카본 페인트 2-3 작은 덧 입힐 적용 후.

- 전도성 페인트가 두 시간 동안 건조하도록 허용합니다.

- 금 - 팔라듐 합금 또는 금 - 상대적으로 무거운 코팅 (40 내지 30 nm의 목표 범위)를 적용하기 위해 사용 설명서에 따라 스퍼터 코터를 운영하고 있습니다. 0.1 밀리바에 시료 챔버 펌프; 40 초에 타이머를 설정합니다. 8:00 위치 (보통 아르곤 가스 유량)에 오픈 세트 밸브. 를 눌러 시작 30mA에서 스퍼터 코팅을 시작합니다. 퍼플 글로우 방전은 시료 챔버에 표시해야한다.

심장 조직 표본의 7 SEM 시험

- 화상 (P)을 최소화하도록 비교적 낮은 가속 전압에서 주사 전자 현미경 수행샘플에서 가난한 전하 손실과 관련된 먹는데는 (충전). 제안 된 초기 영상 조건은 다음과 같습니다 5 kV로는 10mm 작동 거리, 가속 전압.

- 숙련 된 작업자의 도움으로, 고용은 Z 차원에서 상당한 기간 동안 연장하는 다수의 초점면에 섬유 또는 섬유의 초점을 필요로하는 이미징 조건에서 피사계 심도를 확장 할 거리를 작동 증가했다.

- 여기에 사용되는 현미경의 사용자 인터페이스 액세스에, 오른쪽 상단에있는 탐색 탭 (재료의 표 참조).

- 스테이지 메뉴에서 좌표 탭에 액세스 할 수 있습니다. 다음 입력 된 작업 거리에 샘플 단계를 이동하는 탭에 이동을 클릭 좌표 Z에 대한 밀리미터에 더 큰 값을 입력, 작동 거리를 늘립니다.

- 숙련 된 오퍼레이터의 도움으로, 전자선에 관심 직교의 표면 위치를 검지 기울기 및 회전을 이용한다. 10 degr 30의 추가 기울기EES이 위치에서 매트릭스 구조의 관찰과 문서를 향상시킬 수 있습니다.

- 포커스 작동 거리를 지적, 여기에 사용되는 현미경의 경우, (재료의 표 참조) 사용자 인터페이스에 관심 준비된 표면 평면의 주변 근처의 표본을 집중하고 왼쪽 또는 오른쪽으로 슬라이드를 클릭하고 마우스 오른쪽 버튼을 누르고 .

- 표면 반복 초점 반대 가장자리 근처에 이동하는 수동 사용자 인터페이스 조이스틱으로 이동합니다. 거리 작업하는 첫 번째 위치와 대략 동일하지 않은 경우, 경사 시편 (7.2 참조) 및 T의 기울기 값이 좌표 입력 스테이지 메뉴의 좌표 탭을 사용하여 두 위치에서 대략적인 합의를 달성했다.

- 시편을 90도 회전 (필드 좌표 R에 값을 입력) 및 모든 위치가 거의 동일한 작동 거리에서 초점을 맞추고 때까지 과정을 반복합니다.

주 : 변압 SEM은 전하 소산을 개선하기 위해 사용될 수있다가능한 경우. 높은 진공 주사 전자 현미경의 표준 동작 모드이다.

결과

강조 표시된 기술은 사용하지 않는 인간의 심장 이식 기증자 (그림 1), 이식, 야생형과 이영 마우스 (그림 3)에서 마음에서 외식 조직에서 심장 조직에, 그리고 돼지에서 후 심근 경색 심장 샘플에 적용되었다 심장 손상 모델 (그림 2). 도 1에 도시 된 바와 같이, 인간의 심장 행렬은 단면에서 보았을 때, 벌집 형 패턴을 표시 가교 된 단백질의 복잡한 직조이다. 각 '벌집'구조는 그림 1의 평면도를 고려할 때 인터 디스크로 연결하면로드 할 때 은유 '터널'을 통해 길이 실행으로 약 40 μm의 폭, 일반적으로 단일 심근 세포를 우회,., 여러 심근 구상 할 수있다 세 차원으로 확장된다. 또한 1 하이라이트도절삭 가공 (그림 1, 오른쪽) 중 "분쇄"하는 부분보다 정밀도가 더 계시 지형 데이터를 산출로 절단 절차의 중요성, (그림 1, 왼쪽 위).

상주 심장 세포, 혈관 및 SEM 처리에 앞서 순환 세포의 제거는 전체 심장 조직 블록을 SEM으로 덜 감지 될 추가적인 극도의 세부 구조를 폭로한다. 각 콜라겐 "지주"(예를 들어,도 1, 하단 패널) 명백하게 일정한 간격으로 정렬 근섬유 분절 근원 섬유를 수직이다. 이 배열은 스트레칭에 대해 패브릭 몸과 양식을 유지하는 데 도움이 섬유의 '경사와 위사'과 유사한 수축과 이완 사이클 동안 가해 카운터 작용 변형에 의해 심장 구조를 유지 도움에 적합하다.

fo를하기 : 유지-together.within 페이지를 = "1">

그림 1 :. 사용되지 않는 인간의 기증자 심장에서 획득 Decellularized 좌심실 조직의 세포 외 매트릭스의 3 차원 배열의 대표 주사 전자 현미경 사진은 상단이 패널은 낮은 배율 (바 = 500 μm의)에서 단면 행렬을 보여 정상적인 인간의 심장 조직의 구조의 공중보기를 제공한다. 높은 배율에서, 하나는 더 규칙적으로 이격 된 근섬유에 대한 기계적 지원 (가운데 왼쪽과 오른쪽 패널 바 = 100 μm의 50 μm의 각각)을 제공지지 섬유의 일반적인 벌집 모양의 구조를 관찰 할 수있다. 가까이 검사시 각 '벌집'는 수직 주민 심근 (아래 왼쪽과 오른쪽 패널 바 = 각각 10 μm의 5 μm의)에 서로 동안 병렬로 구성되어 섬유로 구성되어있다.ttps : //www-jove-com.remotexs.ntu.edu.sg/files/ftp_upload/54005/54005fig1large.jpg "대상 ="_ 빈 ">이 그림의 더 큰 버전을 보려면 여기를 클릭하십시오.

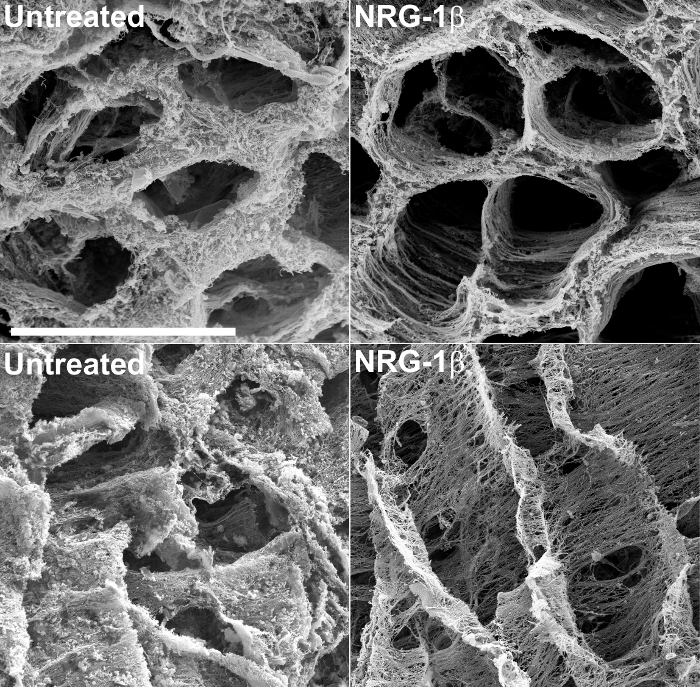

구조 정보를 제공 할뿐만 아니라, decellularized 조직의 SEM은 부상이나 심근 병증의 비 해로운 형태의 질문에 답변 세포 외 기질 변화의 의미, 질적 평가를 할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어,이 기술은 최근 후 경색 돼지 심장 조직 (43)의 외 기질을 조사 하였다. 이 대형 동물 실험의 과정에서 심장 매트릭스의 변화를 눈에 띄는 나타내었다 심부전, 정맥 NRG-1β 투여를받은 후 경색 돼지에 대한 잠재적 치료제로서 NRG-1β의 GGF2 동종의 효과를 평가하기 위해 특별히 설계된 포스트 경색 동물의 치료 심장 조직에 비해. 이 결과는 이후 테 (43)를 발표 하였다chnique이 초기, 뜻밖의 발견에 구축하기위한 유용한 도구를 유지하고있다. (2) 치료 및 NRG-1β 처리 행렬 사이의 격렬한 매트릭스의 차이를 강조하는 연구 과정 중에 생성 예 현미경을 포함 그림.

그림 2 :. 처리되지 않은 및 NRG-1 β 처리 한 돼지에서 왼쪽 심실 세포 외 매트릭스의 대표적인 주사 전자 현미경 사진은, NaOH를 침용 후 단면의 행렬은 치료 후 심근 경색에서 섬유의 규칙적인 공간 배열을 강조 (포스트 MI) 돼지 (왼쪽 위), 후 MI는 NRG-1β 처리 된 동물 (오른쪽) 비교. 경도에서 볼 때, 처리되지 않은 돼지의 행렬은 NRG-1β 처리 된 돼지의 행렬 반면 두꺼운 매트와 같은 모습 (왼쪽 아래)를 전시섬유의 규칙적인 공간 배열 (오른쪽 아래)를 표시합니다. 흰색 막대 = 40 μm의 (전 4 패널). 더 자세한 결과와 수치는 관련 원고 (43)에 포함되어 있습니다. 이 그림의 더 큰 버전을 보려면 여기를 클릭하십시오.

이영 마음에서 발생하는 행렬 변경의 탐험은 뒤 시엔 느 근이영양증 심근증 (DMD)의 동물 모델의 진행 및 개발에 질적 통찰력을 굴복했다. MDX 마우스, DMD의 일반적으로 사용되는 마우스 모델에서, 야생형 및 고정 및 NaOH로 처리 후 SEM 볼 MDX 하트 중 상당한 연령 의존적 차이가있다. 도 3에 도시 된 바와 같이, 매트릭스 성분은 정상 마우스에 작용 디스트로핀 상대적인 결여 6주 된 MDX 하트 비교적 정상이었다. 더 INTeresting, 세포 외 매트릭스 조직은 마음에 DMD의 진보적 인 성격을 보여주는 명확하게 파괴 이하 MDX 쥐에 비해 나이가 디스트로핀 결핍 생쥐에서 아마도 저하되었다. MDX 생쥐 인해 그들이 훨씬 온화한 심근증 표현형과 DMD (48)보다 느린 인간 사망률을 나타낸다는 사실 인간 DMD 심근증의 저조한 대표 때문에 이러한 깊은 차이는 예상되지 않았다. 이는 심장 기능 심지어 작은 변경이 논문에 제시된 시각화 기법을 사용하여 캡처 될 수 있음을 시사한다. 이 방법은 더 현재 마찬가지로 사용할 수 섬유증 타겟팅 치료가되지 않은 다른 장기의 세포 외 매트릭스에 쉽게 적응할 수 있어야합니다.

그림 3 : 왼쪽 벤의 대표적인 주사 전자 현미경 사진MDX 마우스에 비해 야생형에서 tricular 외 매트릭스는. 야생형 마우스에서 좌심실 심근 매트릭스 (상단 패널)의 다른 종에서 관찰 된 것과 유사하다. 나이 6 주에서 MDX 마우스의 행렬은 외관 (가운데 패널)에서 비록 약간 "무성"상대적으로 보통 보인다. 반대로, 이전 MDX 마우스의 심장 행렬은 이영 프로세스 성적 고정 NaOH를 침연 (macerated) 조직에서 SEM을 사용하여 캡처 될 수 있음을 나타낸다 (하단 패널) 심각한 변성 나타난다. 흰색 막대 = 10 μm의 (세 개의 패널). 이 그림의 더 큰 버전을 보려면 여기를 클릭하십시오.

토론

단면 표면 처리 프로토콜 중 가장 중요한 단계입니다. 임계점 건조 공정에 도입 될 때까지 미세 구조를 보존하기 위해 탈수 시험편은 항상 100 % 에탄올에 남아 있어야한다. 따라서 표본의 슬라이스는 표본이 얕은 접시에 에탄올에 잠겨있는 동안 EM 시험을위한 표면을 수행해야합니다 달성했다. 노출 된 표면이 접촉 또는 후속 처리 중에 프로브되지 않는 것이 중요하다. 프로토콜의 SEM 부분에 관계없이 샘플 기원의 기본 전자 현미경 문제 해결이 필요할 수 있지만 더 중요한 수정은 유사한 매트릭스 관측 다른 조직 유형에이 기술의 응용 프로그램에 대한 예상되지 않습니다. 섬유 샘플에서 수집 한 이미지 ( "충전") 나쁨 전하 소산에 의해 도입 된 유물하는 경향이 있습니다. 충전의 문제는 일반적으로 주사 속도를 증가, 가속 전압 (또한 정지 시간을 감소시킴으로써 최소화 될 수있다) 및 전자 빔의 스폿 사이즈를 감소시킨다. 여러 스캔 통합 저속, 높은 품질의 단일 스캔 이미지에 전하 아티팩트없이 잡음 품질 비교 신호의 화상을 생성한다 전하 아티팩트들을 피하기 위해 충분히 빠르게 수집 하였다.

이러한 기술은 본질적으로 질적이며 따라서 정량적 측정 (예를 들면, 메이슨의 트리 크롬 또는 picoserius 레드 염색, 히드 록시 프롤린 함량, 질량 분석법과 RNASeq의 측정) 시각 구조적 차이점은 다양한 발달 또는 질병 상태와 관련 될 수있는 방법을 확인하기 위해 함께 고려 될 때 보완한다. 세포 외 기질은 체내 거의 모든 기관의 필수 구성 요소이기 때문에, 이러한 제한에도 불구하고,이 방법은 특히 심근 섬유증 이후 중요하다. 심장에서 심장 행렬 데프 연속 복잡한 특징으로 펌핑 스트레칭, 비틀림 및 중요 기계적인 지원을 제공합니다인간의 평균 수명 이상 발생> 25 억 비트에 대한 산화 된 혈액과 환원 된 혈액에 (49)의 최적의 입력 및 유출을 부여 ormation. 심장 조직의 매우 낮은 재생 능력을 감안할 때, 상황의 필요에 따라 개조 할 수있는 동적 인 행렬은 논리적 인 의미가 있습니다. 상상 약간만 스트레칭 한 불리한 섬유증을 제한하면서, 치유 과정을 개선하기 위해 매트릭스 개장 조작을위한 치료 표적이 존재한다고 추정 할 수있다. 최소한의 입증 기술의 적용은 심장 행렬의 정교함과 아름다움을 전시하고 그렇게함으로써 더 기능적 중요성을 강조한다.

정량적 측정 값이 거의 모든 실험 연구의 평가를위한 핵심 원칙이지만,이 기술은 현재의 표준 매트릭스 측정을 보완뿐만 아니라 미세 질적 변화를 나타 내기 위해 사용될 수있다 강조된하지만 질적 변화를 강조 근본적인 생화학 적 변화를 이해하기 위해 다른 조사 경로를 제안 할 수 있습니다. 이 기술의 예상되는 장래의 애플리케이션 매트릭스 변화는 질병 과정의 성분되는 기타 기관을 연구는 심장 질환 모델 매트릭스의 변화를 평가하기위한 상보 적 도구로서 인간 조직에서의 사용뿐만 아니라, 넓어진 사용된다.

공개

The authors have nothing to disclose.

감사의 말

This study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIHLB): K01-HL-121045, K08-HL-094703, 5T32HL007411-35, P20 HL101425, U01 HL100398.

Imaging and tissue processing (after NaOH maceration) were performed through the use of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) Cell Imaging Shared Resource (CISR) (supported by NIH grants CA68485, DK20593, DK58404, DK59637 and EY08126). We are especially grateful to the VUMC CISR core directors (Dr. Sam Wells and Dr. W. Gray (Jay) Jerome) for valuable technical advice and also for providing core space and resources for the purposes of filming the technique highlighted in this paper.

We would like to extend our deepest appreciation to Dr. Yan Ru Su and Ms. Kelsey Tomasek in the Cardiology Core Lab for Translational and Clinical Research at Vanderbilt University for providing technical expertise and for collecting human tissue samples used in this study.

자료

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Calcium Chloride | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 12340 | 100 g |

| Carbon Adhesive | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 12664 | 30 g |

| Carbon Adhesive Tabs | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 77825 | order to fit stubs |

| Double Edge Razor Blades Stainless Steel | Ted Pella, Inc | 121-6 | 250/pkg |

| Ethanol | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 15055 | 450 ml |

| Gluteraldehyde, 50% Solution | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 16310 | EM grade, distillation purified |

| Hydrochloric Acid | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 16760 or 16770 | 100 ml |

| Monosodium Phosphate NaH2PO4 | Sigma-Aldrich | S9251-250G | 250 g |

| Osmium Tetroxide | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 19100 | 1 g |

| Silver Conductive Adhesive | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 12686-15 | 15 g |

| Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) | Sigma-Aldrich | S8045-1KG | 1 kg |

| Sodium Phosphate Dibasic (Na2HPO4) | Sigma-Aldrich | S3264-500G | 500 g |

| Tannic Acid, 5% Aqueous | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 21702-5 | 500 ml |

| Trihydrate Sodium Cacodylate | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 12300 | 100 g |

| Gold-palladium Alloy or Gold | Refining Systems, Inc. | varies | specific to the sputter coater make and model |

| Critical Point Dryer | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 850 | |

| Plain Wooden Applicators | Fisher Scientific | 23-400-102 | |

| Quanta 250 Environmental SEM | FEI | Q250 SEM | |

| Sputter Coater | Cressington Scientific Instruments Ltd. | Model 108 | |

| Alluminum SEM Sample Stubs | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 75220-12 | specific to the miscroscope |

참고문헌

- Robinson, T. F., Cohen-Gould, L., Factor, S. M., Eghbali, M., Blumenfeld, O. O. Structure and function of connective tissue in cardiac muscle: collagen types I and III in endomysial struts and pericellular fibers. Scanning Microsc. 2, 1005-1015 (1988).

- Robinson, T. F., Geraci, M. A., Sonnenblick, E. H., Factor, S. M. Coiled perimysial fibers of papillary muscle in rat heart: morphology, distribution, and changes in configuration. Circ Res. 63, 577-592 (1988).

- Lunkenheimer, P. P., et al. The myocardium and its fibrous matrix working in concert as a spatially netted mesh: a critical review of the purported tertiary structure of the ventricular mass. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 29 Suppl 2, S41-S49 (2006).

- Wu, K. C., et al. Late gadolinium enhancement by cardiovascular magnetic resonance heralds an adverse prognosis in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 51, 2414-2421 (2008).

- Kramer, C. M. The expanding prognostic role of late gadolinium enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 48, 1986-1987 (2006).

- Park, S., et al. Delayed hyperenhancement magnetic resonance imaging is useful in predicting functional recovery of nonischemic left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Card Fail. 12, 93-99 (2006).

- Weber, K. T. Cardiac interstitium in health and disease: the fibrillar collagen network. J Am Coll Cardiol. 13, 1637-1652 (1989).

- Jalil, J. E., Janicki, J. S., Pick, R., Abrahams, C., Weber, K. T. Fibrosis-induced reduction of endomyocardium in the rat after isoproterenol treatment. Circ Res. 65, 258-264 (1989).

- Fidzianska, A., Bilinska, Z. T., Walczak, E., Witkowski, A., Chojnowska, L. Autophagy in transition from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy to heart failure. J Electron Microsc (Tokyo). 59, 181-183 (2010).

- Lopez, B., Querejeta, R., Gonzalez, A., Larman, M., Diez, J. Collagen cross-linking but not collagen amount associates with elevated filling pressures in hypertensive patients with stage C heart failure: potential role of lysyl oxidase. Hypertension. 60, 677-683 (2012).

- Gabbiani, G., Ryan, G. B., Majne, G. Presence of modified fibroblasts in granulation tissue and their possible role in wound contraction. Experientia. 27, 549-550 (1971).

- Lorell, B. H. Diastolic dysfunction in pressure-overload hypertrophy and its modification by angiotensin II: current concepts. Basic Res Cardiol. 87 Suppl 2, 163-172 (1992).

- Friedrich, S. P., et al. Intracardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition improves diastolic function in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy due to aortic stenosis. Circulation. 90, 2761-2771 (1994).

- Rosker, C., Salvarani, N., Schmutz, S., Grand, T., Rohr, S. Abolishing myofibroblast arrhythmogeneicity by pharmacological ablation of alpha-smooth muscle actin containing stress fibers. Circ Res. 109, 1120-1131 (2011).

- Yue, L., Xie, J., Nattel, S. Molecular determinants of cardiac fibroblast electrical function and therapeutic implications for atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 89, 744-753 (2011).

- Rohr, S. Myofibroblasts in diseased hearts: new players in cardiac arrhythmias? Heart Rhythm. 6, 848-856 (2009).

- Coen, M., Gabbiani, G., Bochaton-Piallat, M. L. Myofibroblast-mediated adventitial remodeling: an underestimated player in arterial pathology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 31, 2391-2396 (2011).

- Brilla, C. G., Janicki, J. S., Weber, K. T. Cardioreparative effects of lisinopril in rats with genetic hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 83, 1771-1779 (1991).

- Youn, H. J., et al. Relation between flow reserve capacity of penetrating intramyocardial coronary arteries and myocardial fibrosis in hypertension: study using transthoracic Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 19, 373-378 (2006).

- Warnes, C. A., Maron, B. J., Roberts, W. C. Massive cardiac ventricular scarring in first-degree relatives with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 54, 1377-1379 (1984).

- Maron, B. J., Wolfson, J. K., Epstein, S. E., Roberts, W. C. Intramural ('small vessel') coronary artery disease in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 8, 545-557 (1986).

- Olivotto, I., et al. Microvascular function is selectively impaired in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and sarcomere myofilament gene mutations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 58, 839-848 (2011).

- Beltrami, C. A., et al. Structural basis of end-stage failure in ischemic cardiomyopathy in humans. Circulation. 89, 151-163 (1994).

- Factor, S. M., et al. Pathologic fibrosis and matrix connective tissue in the subaortic myocardium of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 17, 1343-1351 (1991).

- Waller, T. A., Hiser, W. L., Capehart, J. E., Roberts, W. C. Comparison of clinical and morphologic cardiac findings in patients having cardiac transplantation for ischemic cardiomyopathy, idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, and dilated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 81, 884-894 (1998).

- Schaper, J., Lorenz-Meyer, S., Suzuki, K. The role of apoptosis in dilated cardiomyopathy. Herz. 24, 219-224 (1999).

- de Leeuw, N., et al. Histopathologic findings in explanted heart tissue from patients with end-stage idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Transpl Int. 14, 299-306 (2001).

- Yoshikane, H., et al. Collagen in dilated cardiomyopathy--scanning electron microscopic and immunohistochemical observations. Jpn Circ J. 56, 899-910 (1992).

- Marijianowski, M. M., Teeling, P., Mann, J., Becker, A. E. Dilated cardiomyopathy is associated with an increase in the type I/type III collagen ratio: a quantitative assessment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 25, 1263-1272 (1995).

- Pearlman, E. S., Weber, K. T., Janicki, J. S., Pietra, G. G., Fishman, A. P. Muscle fiber orientation and connective tissue content in the hypertrophied human heart. Lab Invest. 46, 158-164 (1982).

- Huysman, J. A., Vliegen, H. W., Van der Laarse, A., Eulderink, F. Changes in nonmyocyte tissue composition associated with pressure overload of hypertrophic human hearts. Pathol Res Pract. 184, 577-581 (1989).

- Rossi, M. A. Pathologic fibrosis and connective tissue matrix in left ventricular hypertrophy due to chronic arterial hypertension in humans. J Hypertens. 16, 1031-1041 (1998).

- Lopez, B., Gonzalez, A., Querejeta, R., Larman, M., Diez, J. Alterations in the pattern of collagen deposition may contribute to the deterioration of systolic function in hypertensive patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 48, 89-96 (2006).

- Krayenbuehl, H. P., et al. Left ventricular myocardial structure in aortic valve disease before, intermediate, and late after aortic valve replacement. Circulation. 79, 744-755 (1989).

- Schwarz, F., et al. Myocardial structure and function in patients with aortic valve disease and their relation to postoperative results. Am J Cardiol. 41, 661-669 (1978).

- Hein, S., et al. Progression from compensated hypertrophy to failure in the pressure-overloaded human heart: structural deterioration and compensatory mechanisms. Circulation. 107, 984-991 (2003).

- Brooks, W. W., Shen, S. S., Conrad, C. H., Goldstein, R. H., Bing, O. H. Transition from compensated hypertrophy to systolic heart failure in the spontaneously hypertensive rat: Structure, function, and transcript analysis. Genomics. 95, 84-92 (2010).

- O'Hanlon, R., et al. Prognostic significance of myocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 56, 867-874 (2010).

- Green, J. J., Berger, J. S., Kramer, C. M., Salerno, M. Prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement in clinical outcomes for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 5, 370-377 (2012).

- Frankel, K. A., Rosser, R. J. The pathology of the heart in progressive muscular dystrophy: epimyocardial fibrosis. Hum Pathol. 7, 375-386 (1976).

- Otto, R. K., Ferguson, M. R., Friedman, S. D. Cardiac MRI in muscular dystrophy: an overview and future directions. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 23, 123-132 (2012).

- Finsterer, J., Stollberger, C. The heart in human dystrophinopathies. Cardiology. 99, 1-19 (2003).

- Galindo, C. L., et al. Anti-remodeling and anti-fibrotic effects of the neuregulin-1beta glial growth factor 2 in a large animal model of heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 3, e000773(2014).

- Caulfield, J. B., Borg, T. K. The collagen network of the heart. Lab Invest. 40, 364-372 (1979).

- Ohtani, O. Three-dimensional organization of the connective tissue fibers of the human pancreas: a scanning electron microscopic study of NaOH treated-tissues. Arch Histol Jpn. 50, 557-566 (1987).

- Rossi, M. A., Abreu, M. A., Santoro, L. B. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Connective tissue skeleton of the human heart: a demonstration by cell-maceration scanning electron microscope method. Circulation. 97, 934-935 (1998).

- Icardo, J. M., Colvee, E. Collagenous skeleton of the human mitral papillary muscle. Anat Rec. 252, 509-518 (1998).

- McGreevy, J. W., Hakim, C. H., McIntosh, M. A., Duan, D. Animal models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: from basic mechanisms to gene therapy. Dis Model Mech. 8, 195-213 (2015).

- Buckberg, G., Hoffman, J. I., Mahajan, A., Saleh, S., Coghlan, C. Cardiac mechanics revisited: the relationship of cardiac architecture to ventricular function. Circulation. 118, 2571-2587 (2008).

재인쇄 및 허가

JoVE'article의 텍스트 или 그림을 다시 사용하시려면 허가 살펴보기

허가 살펴보기This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. 판권 소유