Method Article

מיקרוסקופ אלקטרוני סורק של רקמות macerated לדמיין את תאי מטריקס

In This Article

Summary

Shown here is a method for visualizing extracellular matrix ultrastructure in decellularized cardiac tissues.

Abstract

Fibrosis is a component of all forms of heart disease regardless of etiology, and while much progress has been made in the field of cardiac matrix biology, there are still major gaps related to how the matrix is formed, how physiological and pathological remodeling differ, and most importantly how matrix dynamics might be manipulated to promote healing and inhibit fibrosis. There is currently no treatment option for controlling, preventing, or reversing cardiac fibrosis. Part of the reason is likely the sheer complexity of cardiac scar formation, such as occurs after myocardial infarction to immediately replace dead or dying cardiomyocytes. The extracellular matrix itself participates in remodeling by activating resident cells and also by helping to guide infiltrating cells to the defunct lesion. The matrix is also a storage locker of sorts for matricellular proteins that are crucial to normal matrix turnover, as well as fibrotic signaling. The matrix has additionally been demonstrated to play an electromechanical role in cardiac tissue. Most techniques for assessing fibrosis are not qualitative in nature, but rather provide quantitative results that are useful for comparing two groups but that do not provide information related to the underlying matrix structure. Highlighted here is a technique for visualizing cardiac matrix ultrastructure. Scanning electron microscopy of decellularized heart tissue reveals striking differences in structure that might otherwise be missed using traditional quantitative research methods.

Introduction

Fibrosis disrupts the normal myocardial collagen network, which is critical for normal mechanistic functions of cardiomyocytes 1,2 as well as for inter-cellular communication, intracellular signaling, and cell survival 3. The development of fibrosis is a major determinant of cardiac function, and fibrotic remodeling of the cardiac interstitium arising from a variety of etiologies leads to increased left ventricular stiffness and diastolic dysfunction 4. Myocardial fibrosis may also lead to arrhythmias, and whether the progression of fibrotic remodeling is a general or local phenomenon, it is highly associated with a poor prognosis in patients with ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy 5. Likewise, the absence of myocardial fibrosis is a strong predictor of ventricular functional recovery and long-term survival 6.

The hallmark of fibrosis is the deposition of excess collagen, which has the tensile strength of steel 7 and can adversely affect cardiomyocyte function on multiple levels. Mechanical forces resulting from an excessively collagenous matrix can lead to cardiomyocyte atrophy 8,9, passive tissue stiffness 10, tonic contraction-induced myocardial stiffness 11-13, and reduced delivery of oxygen to the remaining population of cardiomyocytes. Gap junction coupling of cardiomyocytes and myoFbs can also compromise the heart's electrical characteristics, creating a greater risk for the development of arrhythmias 14-16. Perivascular fibrosis alters vasomotor reactivity of intramural coronary arteries and arterioles 17 and contributes to luminal narrowing that reduces the supply of oxygen and thus the survival of cardiomyocytes 17-22. Pathogenic fibrotic and electrical remodeling, emanating from an initial site of ischemic injury or energy imbalance, inevitably progresses to heart failure.

Cardiomyocyte necrosis initiates the fibrotic response, and subsequent adverse fibrotic remodeling can occur irrespective of etiology. Finding a way to control cardiac fibrosis would be clinically beneficial for the treatment of ischemic and idiopathic cardiomyopathies, hypertensive heart disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease and dystrophinopathies 23-42. Regardless of how the fibrotic disease process begins, soluble, profibrotic factors can cross the interstitial space and provoke activation of interstitial and adventitial fibroblasts at sites remote to the initial fibrotic scar, creating a cascade effect that ultimately leads to heart failure. The optimum scenario would be to exploit the fibrillogenic process using a targeted therapeutic that can be applied during the compensative hypertrophic stage of cardiomyopathy before it progresses to systolic pump failure, diastolic heart failure, or other end-stage outcomes. The ultimate goal would be to reverse fibrosis so that dead cardiomyocytes can be replaced and heart function restored completely.

The importance of the matrix is widely understood, yet methods to study the matrix are limited mainly to quantitative measurements of major structural components, particularly collagen, and relative levels of different matrix and matricellular proteins. This protocol highlights a rarely used technique that is useful for assessing qualitative differences in the cardiac matrix. This technique has been recently used to compare and contrast fundamental differences in heart matrices from different etiologies of heart disease (in human explants), to examine hearts from post-infarcted pigs treated with the glial growth factor (GGF) isoform of neuregulin-1β, relative to untreated animals 43, and to probe for differences in the matrices of cardiac tissues from mdx mice (a commonly used animal model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy) at different ages and compared to wild-type controls. This technique was first introduced by Drs. Caulfield and Borg in 1979 44, but few studies have since employed this powerful technique 45-47, re-introduced here with only slight modification. This methodology is a valuable research tool, because it provides qualitative information about extracellular matrix ultrastructure that might otherwise be overlooked when simply measuring matrix component content and/or level of fibrosis.

Protocol

משפט ואתיקה: הפרוטוקולים עבור טיפול בבעלי חיים אושרו על ידי הטיפול בבעלי החיים המוסדי ונדרבילט ועדת שימוש (IACUC, פרוטוקולי מספר M / 10/117 (חזירים) ו- M / 10/219 (עכברים) ו נערכים על פי תקני AAALAC-בינלאומיים. שימוש של רקמות לב אנושיות פקידה אושר על ידי IRB במרכז הרפואי של האוניברסיטה ונדרבילט (מספר פרוטוקול 100,887).

לדוגמא 1. איסוף ואחסון

- הפוך glutaraldehyde 4% טרי ב 0.1 M חיץ פוספט פתרון (PB).

זהירות: Glutaraldehyde הוא רעיל, ללבוש כפפות ולעבוד במנדף.- בצע פתרון 0.2 M המניות של PB, pH 7.4 באמצעות 21.8 גרם Na 2 HPO 4 ו -6.4 גרם לאא 2 4 PO. Quantum satis (QS) 1,000 מ"ל DH 2 O.

- להוסיף 400 μl של glutaraldehyde 50% עד 2.5 מ"ל של פתרון המניות PB ו -2.1 מ"ל DH 2 O.

- לטבול נתח (לא גדול מ -2 גמ '2) של רקמה לתוך פתרון glutaraldehyde 4%. הערה: חתיכות קטנות יכולות לשמש גם אבל צריך להיות בגודל מספיק (לא קטן מ -5 מ"מ 2) להיות מדמיינים בקלות על ידי עין על מנת להקל צעדים מאוחר יותר של הפרוטוקול.

- דגירה בטמפרטורת החדר למשך שעה 1, ולאחר מכן לאחסן לזמן בלתי מוגבל ב 4 ° C..

2. Decellularization של רקמת לב

- הפוך בתמיסה מימית NaOH 10% טריים באמצעות 10 כדורי גרם NaOH / 100 מ"ל DH 2 O.

זהירות: פתרונות NaOH הם מאכלים והוא יכול לגרום אלקלי כוויות, ללבוש כפפות. - לשטוף רקמות ב DH 2 O.

- דגירה בתמיסה 10% NaOH בטמפרטורת החדר למשך 6 - 10 ימים (עד שינויים ברקמה מן אדמדם-חום מחוץ לבן או לבן).

- יש לשטוף ב DH 2 O עד הרקמה הופכת שקופה.

- לטבול רקמות בחומצה טאני 1% ל -4 שעות בטמפרטורת החדר. השתמש 1 מ"ל 5% מניות פתרון לכל 4 מ"ל DH 2 O.

זהירות: חומצה טאניתהוא מגרה חזק, ללבוש כפפות. - יש לשטוף ב DH 2 O לילה.

3. Osmication והתייבשות של רקמת לב (ב פומה הוד לבטיחות)

- בצע פתרון 0.2 M המניות של חיץ נתרן cacodylate באמצעות cacodylate 21.4 גרם נתרן, סידן כלורי 10.0 גרם ו 450 מ"ל DH 2 O. מערבבים, ולאחר מכן להוסיף חומצה הידרוכלורית לפי הצורך כדי להתאים את pH 7.4. Qs 500 מ"ל עם DH 2 O.

זהירות: cacodylate נתרן וחומצה הידרוכלורית רעילים, ללבוש כפפות ולעבוד במנדף. - הפוך פתרון המניות 2% מימית של tetroxide אוסמיום במנדף לבטיחות ידי המסת גביש tetroxide אוסמיום 1 גרם ב 50 מ"ל DH 2 O.

זהירות: tetroxide אוסמיום הוא מפגע משאיפת חמור; קיבעון האדים של ממברנות ריר או העיניים אפשרי, ומכאן להתמודד רק במנדף עם כפפות. שומר סנסציה מומלצת. - לשטוף רקמות במאגר cacodylate 0.1 M נתרן (לערבב פתרון מניות 1: 1 עם DH 2 O) במשך 5 דקות על הכתף (או תסיסה עדינה).

- חזור על השלב הקודם פעמיים, עבור סכום כולל של שלוש שטיפות חיץ.

- לטבול רקמות tetroxide אוסמיום 1% ב 0.1 M נתרן חיץ cacodylate (לערבב cacodylate נתרן המניות אוסמיום המניות tetroxide 1: 1) על הכתף במשך שעה 1.

- לשטוף רקמות 0.1 M נתרן cacodylate חיץ 3 פעמים במשך 5 דקות כל אחד על הכתף.

- לשטוף רקמות באמצעות ריכוזים גוברים של אתנול (30%, 50%, 75%, 85%, 95%, ולבסוף 100%) במשך 15 דקות כל אחד על כתף.

4. הכנת פני שטח חתך עבור SEM

- העברת רקמות באתנול 100% כדי בצלחת פטרי רדודה גם המכילה אתנול 100%.

- להחזיק שני סכיני גילוח חד מאוד כך ולדירות הצדדים נמצאות בקשר אחד עם השני, וצלב קצות החיתוך ליצירת שני צדדים של משולש שווה צלעות מעל הדגימה. כדי להשיג זאת, להשתמש ביד שמאל למקום להב אחד בצד הימני או השמאלי של המדגםחתך שמאלה. במקביל, השתמש ביד ימין להציב את הלהב השני בשמאל הקיצוני של ימינה המדגם פרוס. לפיכך, הלהבים יהיו החליקו אחד נגד השני מכיוונים מנוגדים לעשות חתך אחד חלקה.

- חלק את צדדי להב שטוח אחד נגד השני כדי לעשות חתך מאוד נקי של הדגימה עם עיוות מינימאלית או לקרוע כוח, רצוי לחשוף שטח פנים גדול ככל האפשר מבלי לפגוע הדגימה.

- חזור על פעולה עבור כל דגימה לחשוף משטחי החתך האפשריים הנקיים לבדיקה ב SEM.

5. ייבוש נקודה קריטית (CPD) של רקמת לב

- השתמש מרית או פינצטה להעביר רקמות לבעל המדגם של מייבש הנקודה הקריטי (CPD), להבטיח כי נשארה רקמה באתנול 100% בכל העת. ודא כי בעל שקוע אתנול כי העברת מושגת עם הרקמה החשופה לאוויר לא יותר מכמה שניות.

- Operate CPD לכל לנוהוראות אה להשלים 3 טיהור-ו-למלא מחזורים להחליף אתנול עם פחמן דו חמצני נוזלי.

- Operate CPD לכל ידנית של המשתמש כדי להשיג ייבוש נקודה קריטית של דגימות ולהחזיר אותם בלחץ אטמוספרי עם אוורור מבוקר של CO 2.

שמת 6. דוגמאות רקמה לב עבור SEM

- כן בדל מדגם SEM עבור כל דגימה, על ידי דבקות כרטיסייה דבקה פחמן אל פני השטח העליון של בדל האלומיניום.

- בעזרת סטראו, בזהירות לדבוק דגימה ללשונית הדבקה עם משטח החתך של עניין פונה כלפי מעלה (הרחק הכרטיסייה, גלויה), וקרוב ככל האפשר מקבילה עם המטוס של פני שטח בדל מדגם. אין לחקור או לגעת במשטח של עניין.

- לשבור מקל מוליך עץ כדי להשיג מברשת מחודדת, אידיאלית עבור יישום צבע. החל כסף או צבע פחמן בבסיס והדפנות של הדגימה, כדי לשפר את דבקות הבדל.

- הרחב קו דק מאוד של כסף או פחמן לצייר עד יתרון של פני השטח של עניין, כדי לספק נתיב תשלום מפני השטח של עניין הקרקע.

- החל 2 או 3 מורח קטן של כסף או צבע פחמן מסביב בכרטיסיית פחמן, כדי לספק נתיב מוליך מפני שטח כרטיסיית פחמן אל בדל מתכת ובכך לקרקע.

- אפשר צבע מוליך להתייבש במשך שתי שעות.

- Operate coater גמגום לכל מדריך למשתמש להחיל ציפוי כבד יחסית (טווח היעד של 30 - 40 ננומטר) של סגסוגת זהב-פלדיום או זהב. משאבת תא דגימה כ -0.1 mbar; כוונו את הטיימר ל -40 שניות. שסתום סט פתוח 08:00 המיקום (זרימת גז ארגון מתון). לחצו על התחל כדי ליזום ציפוי גמגום 30 מילי-אמפר. הפרשות זוהרות סגולות צריכות להיות גלויות בתא הדגימה.

7. בדיקת SEM של דגימות רקמת לב

- לבצע סריקה מיקרוסקופית אלקטרונים במתח האצה נמוך יחסית כדי למזער הדמיה problems הקשורים פיזור חסותה המסכן במדגם (טעינה). מצב הדמיה הראשונית מוצעים הם: 5 kV מאיץ מתח, 10 מ"מ ומרחק עבודה.

- עם סיוע של מפעיל מנוסה, להעסיק גדל עובד מרחק להאריך עומק השדה בתנאי הדמיה הדורשים מוקד הסיבים במטוסים מספר מוקדים, או סיבי הארכה עבור אורך ניכר בממד z.

- עבור המיקרוסקופ משמש כאן (ראה טבלה של חומרים), בתוך גישת הממשק המשתמש על כרטיסיית הניווט ב ימני עליון.

- גש לכרטיסיית הקואורדינטות מתפריט השלב. כדי להגדיל מרחק עבודה, זן ערך גדול במילימטרים עבור Z קואורדינטות ואז ללחוץ על עבור לכרטיסייה כדי להזיז את הבמה מדגם למרחק עובד נכנס.

- עם סיוע של מפעיל מנוסה, להעסיק הטית דגימה וסיבוב כדי למקם את השטח של מאונך המעניין את אלומת האלקטרונים. הטיה נוספת של 10 עד 30 degrEES מתוך עמדה זו עשויה לשפר תצפית ותיעוד של המבנה מטריקס.

- עבור המיקרוסקופ משמש כאן (ראה טבלה של חומרים), בממשק המשתמש, לחץ לחיצה ממושכת על כפתור העכבר הימני, ולאחר מכן חלק שמאלה או ימינה כדי למקד את הדגימה ליד בפריפריה של מטוס המשטח המוכן של עניין, תוך ציון מרחק העבודה הממוקד .

- נווט עם ג'ויסטיק הממשק הידני על מנת לעבור ליד הקצה היריב של מוקד השטח וחזור. אם עובדי מרחק אינו שווה בערך במיקום הראשון, דגימה להטות להשיג סכם משוער בשני המקומות באמצעות לשונית הקואורדינטות של תפריט השלב (ראה 7.2) והזנת ערך הטיה של T לתאם.

- סובב דגימה תשעים מעלות (להזין ערך לתוך R לתאם שדה) וחזור על התהליך עד שכל העמדות ממוקדות על מרחק העבודה הזהה כ.

הערה: SEM לחץ משתנה עשוי להיות מועסק על מנת לשפר את פיזור תשלוםאם זמין. ואקום גבוה הוא מצב הפעלה סטנדרטית עבור במיקרוסקופ אלקטרונים סורק.

תוצאות

הטכניקה המודגשת יושמה לרקמות לב מתורם השתלת לב אנושית בשימוש (איור 1), רקמות explanted מן המושתלים, לבבות מ wild-type ועכברים דיסטרופי (איור 3), ו בדגימות לב אוטם שלאחר שריר לב מתוך חזירים מודל של פגיעה לבבית (איור 2). כפי שניתן לראות בתרשים 1, מטריצת לב האדם הוא מארג מורכב של חלבונים צולבים המציגים דפוס חלת דבש דמוי כאשר צפו ב חתך. "חלת דבש" כל מבנה הוא כ 40 מיקרומטר רחב, עקיף בדרך כלל myocyte יחיד, כאשר בוחנים את נוף המישורים באיור 1. כאשר מחובר באמצעות דיסקי intercalated, כמה cardiomyocytes ניתן שנחזה מוט פועל לאורכה דרך "המנהרה" כאשר מטאפורה מורחב-ממדי שלוש. איור 1 גם מדגיש את החשיבות של הליך החיתוך, בדייקנות רבה יותר מניב נתונים טופוגרפיים וחושפניים יותר (איור 1, שמאלי עליון) מאשר חלקים כי הם "שברו" במהלך תהליך החיתוך (איור 1, בפינה ימנית עליונה).

הסרת תאי לב תושב, כלי דם, ואת דם תאים לפני עיבוד SEM חושפת פרטים אולטרה-מבניים נוספים זה יהיה פחות ניכר ידי SEM של בלוקים שלמים רקמה לב. כל "יתד" collagenous פרט, למשל (איור 1, לוחות למטה) מיושר כנראה במרווחי זמן קבועים וניצבת myofibril סרקומר. הסדר זה אינו מתאים עוזר לשמור על מבנה הלב על ידי דפורמציות מתנהג ללא מרשם המופעל במהלך מחזורי התכווצות והרפיה, בדומה 'השתי weft' של טקסטיל המסייע לשמור על הגוף בד צורה שהיא נגד מתיחה.

FO: keep-together.within-page = "1">

איור 1:. נציג אלקטרונים סורק micrographs ההסדר תלת ממדי של תאי מטריקס רקמות decellularized השמאל חדרית המתקבל לב התורם האדם בשימוש הפאנלים שני העליון להראות המטריצה חתך בהגדלה נמוכה (מוטות = 500 מיקרומטר), מתן מבט אווירי על הארכיטקטורה של רקמת לב אדם נורמלית. בהגדלה גבוהה, אפשר יותר טוב להתבונן במבנה חלת הדבש דמוי הטיפוסי של סיבי תומכת המספקים תמיכה מכאנית עבור myofibers פזורות (מוטה פנל על ימין ועל שמאל באמצע = 100 מיקרומטר ו 50 מיקרומטר, בהתאמה). לאחר בדיקה מקרוב, כל 'חלת דבש' מורכב סיבים מאורגנים במקביל אחד עם השני תוך בניצב cardiomyocytes תושב (מוטות פאנל על ימין ועל שמאל התחתון = 10 מיקרומטר ו -5 מיקרומטר, בהתאמה).ttps: //www-jove-com.remotexs.ntu.edu.sg/files/ftp_upload/54005/54005fig1large.jpg "target =" _ blank "> לחץ כאן כדי לצפות בגרסה גדולה יותר של דמות זו.

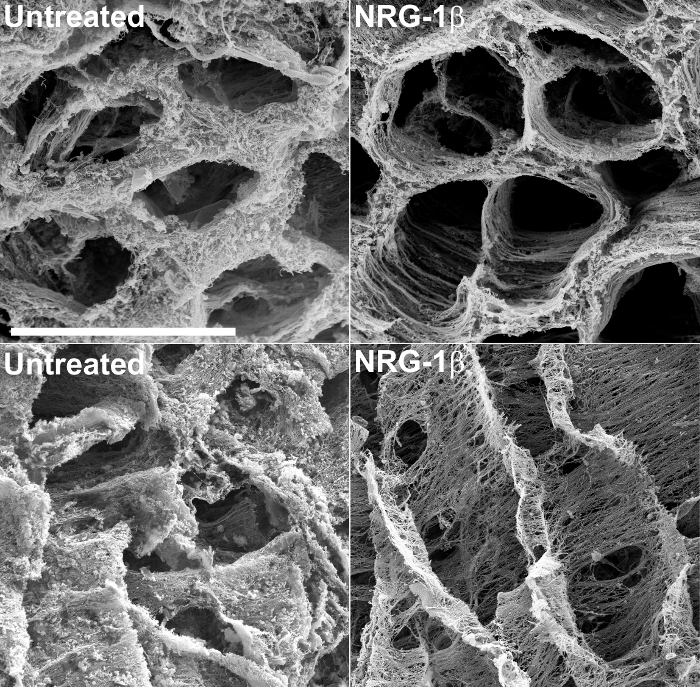

בנוסף לאספקת מידע מבני, SEM של רקמות decellularized יכול לאפשר הערכה אמתית, איכותית של שינויי מטריקס בתגובה לפציעה או צורות בלתי מזיקות של קרדיומיופתיה. לדוגמא, טכניקה זו שמשה לאחרונה לבחון את המטריצות התאיות של רקמות לב חזירים שלאחר אוטם 43. במהלך הניסוי בקנה החיה הזו, שתוכנן במיוחד כדי להעריך את היעילות של איזופורם GGF2 של NRG-1β כמו טיפולי פוטנציאל אי ספיקת לב, שלאחר אוטם חזירים אשר קבלו ממשל NRG-1β תוך ורידים הציגו בולט שינויים במטריצת הלב בהשוואה לרקמות לב מטופל של חיות שלאחר אוטם. תוצאות אלו ובהמשך פורסמו 43, ואת technique נותר כלי רב ערך עבור התבססות על, ראשוני זה גילוי אקראי. איור 2 כולל micrographs למשל, פיק במהלך המחקר, אשר מדגיש הבדלי מטריקס דרסטי בין מטופל ומטריצות NRG-1β שטופלו.

איור 2:. נציג אלקטרונים סורק micrographs של השמאל חדרית תאי מטריקס שלא טופלו ו NRG-1 β חזירים -treated, לאחר NaOH שריה המטריצה חתך מדגיש את הסידור המרחבי קבוע של סיבי לאוטם מטופל פוסט-שריר הלב (לאחר MI) חזירים (למעלה משמאל), לעומת לאחר MI חיות NRG-1β שטופלו (בצד שמאל למעלה). כאשר צפו ב אורך, מטריצת חזירי מטופל מפגינה חזות עבה, כמו-מט (למטה משמאל), ואילו מטריקס חזירים שטופל NRG-1βמציג הסידור המרחבי סדירה של סיבים (מימין למטה). בר לבן = 40 מיקרומטר (כל ארבעת הלוחות). תוצאות נוספות ודמויות מפורטות כלולות בכתב היד הקשור 43. אנא לחץ כאן כדי לצפות בגרסה גדולה יותר של דמות זו.

חקר השינויים מטריקס המתרחשים לבבות דיסטרופי גם הניב תובנות איכותיות לתוך התקדמות ופיתוח במודל חיה של קרדיומיופתיה ניוון שרירים דושן (DMD). בעכברי MDX, במודל של עכברים נפוץ של DMD, ישנם הבדלים משמעותיים וגיל תלוי בין wild-type ולבבות MDX כאשר נצפים על ידי SEM לאחר קיבוע וטיפול NaOH. כפי שניתן לראות בתרשים 3, רכיבי מטריצה היו תקינים יחסית 6 שבועות בן לבבות MDX החסרים ביחס בדיסטרופין פונקציונלי לעכברים רגילים. עוד interesting, ארגון מטריקס שובש בבירור או אולי מושפל בעכברים בדיסטרופין מחסר מבוגרים בהשוואה לעכברי MDX צעירים, הממחיש את הפרוגרסיביות של DMD בלב. כאלה הבדלים עמוקים לא ציפו, כי עכברי MDX מייצגים גרועים של קרדיומיופתיה אדם DMD בשל העובדה כי הם מפגינים פנוטיפ קרדיומיופתיה הרבה יותר מתונים שיעור תמותה איטי יותר מאשר בני אדם עם DMD 48. הדבר מצביע על כך אפילו שינויים קטנים בתפקוד הלב יכול ליפול בפח באמצעות טכניקה ויזואליזציה הציג בכתב היד הזה. מתודולוגיה זו צריכה גם להיות בעל יכולת הסתגלות בקלות אל המטריצות התאיות של איברים אחרים, שעבורם אין גם זמינים כרגע טיפולי מיקוד-פיברוזיס.

איור 3: נציג אלקטרוני סורק micrographs של השמאל Ventricular מטריקס ב wild-type לעומת עכברים MDX. המטריצה הלב של חדר שמאל ב עכברי-בר (הפאנל העליון) דומה לזה שנצפה מינים אחרים. המטריצה בעכברים MDX לאחר 6 שבועות של גיל נראה יחסית נורמלי, אם כי מעט "רכות" במראה (פאנל באמצע). לעומת זאת, מטריצת הלב של עכברי MDX מבוגרים נראית מנוונת קשה (פנל תחתון), המציין כי תהליך דיסטרופי ניתן ללכוד איכותי באמצעות SEM ברכוש קבוע, רקמות-macerated NaOH. = 10 מיקרומטר בר לבנים (כל שלושת פנלים). נא ללחוץ כאן כדי לצפות בגרסה גדולה יותר של דמות זו.

Discussion

הכנת שטח חתך היא השלב הקריטי ביותר במהלך הפרוטוקול. כדי לשמר מבנה עדין, דגימות מיובשות חייבות להישאר באתנול 100% בכל העת עד הציגו את תהליך ייבוש נקודה הקריטי. לכן החיתוך של דגימות כדי להשיג משטחים לבדיקה EM חייב להיעשות תוך דגימות קומטי באתנול בצלחת רדודה. זה גם קריטי, כי המשטח החשוף לא נגע או נחקר במהלך טיפול שלאחר מכן. אין שינויים גדולים צפויים עבור יישום של טכניקה זו כדי סוגי רקמות אחרים לתצפיות מטריקס דומות, אם כי חלק SEM של הפרוטוקול עשוי לדרוש פתרון בעיות במיקרוסקופ אלקטרונים בסיסיים ללא הבדל מוצא מדגם. תמונות שנאספו מהמדגמים הסיביים מועדי חפצים הציגו ידי פיזור תשלום עלוב ( "טעינה"). בעיות טעינה בדרך כלל ניתן למזער על ידי הפחתת מאיץ מתח, גברת מהירות סריקה (להתעכב זמן המכונה גםנקודה) והפחתת גודל של אלומת אלקטרונים. שילוב של כמה סריקות שנאסף מספיק מהר כדי למנוע חפצי תשלום יפיק תמונה של אות להשוות איכות רעש ללא ממצאי התשלום נוכחים תמונת סריקה בודדת איכות איטית, גבוהה.

טכניקה זו היא מטבעה איכותית ובכך משלימה כאשר הם מוצגים לצד מדידות כמותיות (למשל, trichrome של מייסון או picoserius מכתים אדום, מדידת תוכן hydroxyproline, ספקטרומטריית מסת RNA-seq) כדי לברר כיצד הבדלים מבניים דמיינו עשויים להיות קשורים למדינות התפתחותית או מחלה שונות. עם זאת, למרות מגבלה זו, השיטה היא משמעותית מעבר סיסטיק לב במיוחד, כי מטריקס היא מרכיב חיוני של כמעט כל איבר בגוף. בלב, מטריצת הלב מספקת תמיכה מכאנית קריטית לשאיבה רציפה המאופיינות מורכב מתיחות, סיבובים, ו deformation, מקנת כניסה בזרימה אופטימלית של דם מחומצן ו deoxygenated 49 עבור> 2.5 מיליארדים פעימות המתרחשות על פני תוחלת החיים של האדם הממוצע. בהינתן יכולת ההתחדשות נמוכה מאוד של רקמת לב, מטריצה דינמית שיכול להיות מחדש בהתאם לצרכי קשר היא דבר הגיוני. עם רק מתיחה קלה של הדמיון, אפשר להסיק כי קיימים טיפולית מעניינת מניפולציה שיפוץ מטריקס על מנת לשפר את תהליך הריפוי, תוך הגבלת סיסטיק לוואי. יישום של הטכניקה הפגינו לכל הפחות מציג את התחכום והיופי של מטריקס לב ותוך כדי כך מדגיש עוד יותר חשיבות הפעילות שלה.

בעוד הערך של מדדי כמותיים הוא עיקרון מרכזי להערכה כמעט כל הניסויים, הטכניקה מודגשת כאן ניתן להשתמש כדי לחשוף וריאציות ultrastructural איכותיות שלא רק להשלים מדידות מטריקס רגילותאבל עשוי להציע נתיבי חקירה חלופיים להבין את השינויים הביוכימיים יסוד המדגישים את השינויים האיכותיים. יישומים עתידיים צפויים של טכניקה זו הם השימוש בו מודלי מחלות-לב ברקמות אנושיות ככלים משלים להערכת שינויי מטריקס, כמו גם שימוש התרחב ללמוד ואברים אחרים אשר שינויי מטריקס הם מרכיב של תהליך המחלה.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIHLB): K01-HL-121045, K08-HL-094703, 5T32HL007411-35, P20 HL101425, U01 HL100398.

Imaging and tissue processing (after NaOH maceration) were performed through the use of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) Cell Imaging Shared Resource (CISR) (supported by NIH grants CA68485, DK20593, DK58404, DK59637 and EY08126). We are especially grateful to the VUMC CISR core directors (Dr. Sam Wells and Dr. W. Gray (Jay) Jerome) for valuable technical advice and also for providing core space and resources for the purposes of filming the technique highlighted in this paper.

We would like to extend our deepest appreciation to Dr. Yan Ru Su and Ms. Kelsey Tomasek in the Cardiology Core Lab for Translational and Clinical Research at Vanderbilt University for providing technical expertise and for collecting human tissue samples used in this study.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Calcium Chloride | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 12340 | 100 g |

| Carbon Adhesive | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 12664 | 30 g |

| Carbon Adhesive Tabs | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 77825 | order to fit stubs |

| Double Edge Razor Blades Stainless Steel | Ted Pella, Inc | 121-6 | 250/pkg |

| Ethanol | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 15055 | 450 ml |

| Gluteraldehyde, 50% Solution | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 16310 | EM grade, distillation purified |

| Hydrochloric Acid | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 16760 or 16770 | 100 ml |

| Monosodium Phosphate NaH2PO4 | Sigma-Aldrich | S9251-250G | 250 g |

| Osmium Tetroxide | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 19100 | 1 g |

| Silver Conductive Adhesive | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 12686-15 | 15 g |

| Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) | Sigma-Aldrich | S8045-1KG | 1 kg |

| Sodium Phosphate Dibasic (Na2HPO4) | Sigma-Aldrich | S3264-500G | 500 g |

| Tannic Acid, 5% Aqueous | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 21702-5 | 500 ml |

| Trihydrate Sodium Cacodylate | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 12300 | 100 g |

| Gold-palladium Alloy or Gold | Refining Systems, Inc. | varies | specific to the sputter coater make and model |

| Critical Point Dryer | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 850 | |

| Plain Wooden Applicators | Fisher Scientific | 23-400-102 | |

| Quanta 250 Environmental SEM | FEI | Q250 SEM | |

| Sputter Coater | Cressington Scientific Instruments Ltd. | Model 108 | |

| Alluminum SEM Sample Stubs | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 75220-12 | specific to the miscroscope |

References

- Robinson, T. F., Cohen-Gould, L., Factor, S. M., Eghbali, M., Blumenfeld, O. O. Structure and function of connective tissue in cardiac muscle: collagen types I and III in endomysial struts and pericellular fibers. Scanning Microsc. 2, 1005-1015 (1988).

- Robinson, T. F., Geraci, M. A., Sonnenblick, E. H., Factor, S. M. Coiled perimysial fibers of papillary muscle in rat heart: morphology, distribution, and changes in configuration. Circ Res. 63, 577-592 (1988).

- Lunkenheimer, P. P., et al. The myocardium and its fibrous matrix working in concert as a spatially netted mesh: a critical review of the purported tertiary structure of the ventricular mass. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 29 Suppl 2, S41-S49 (2006).

- Wu, K. C., et al. Late gadolinium enhancement by cardiovascular magnetic resonance heralds an adverse prognosis in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 51, 2414-2421 (2008).

- Kramer, C. M. The expanding prognostic role of late gadolinium enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 48, 1986-1987 (2006).

- Park, S., et al. Delayed hyperenhancement magnetic resonance imaging is useful in predicting functional recovery of nonischemic left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Card Fail. 12, 93-99 (2006).

- Weber, K. T. Cardiac interstitium in health and disease: the fibrillar collagen network. J Am Coll Cardiol. 13, 1637-1652 (1989).

- Jalil, J. E., Janicki, J. S., Pick, R., Abrahams, C., Weber, K. T. Fibrosis-induced reduction of endomyocardium in the rat after isoproterenol treatment. Circ Res. 65, 258-264 (1989).

- Fidzianska, A., Bilinska, Z. T., Walczak, E., Witkowski, A., Chojnowska, L. Autophagy in transition from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy to heart failure. J Electron Microsc (Tokyo). 59, 181-183 (2010).

- Lopez, B., Querejeta, R., Gonzalez, A., Larman, M., Diez, J. Collagen cross-linking but not collagen amount associates with elevated filling pressures in hypertensive patients with stage C heart failure: potential role of lysyl oxidase. Hypertension. 60, 677-683 (2012).

- Gabbiani, G., Ryan, G. B., Majne, G. Presence of modified fibroblasts in granulation tissue and their possible role in wound contraction. Experientia. 27, 549-550 (1971).

- Lorell, B. H. Diastolic dysfunction in pressure-overload hypertrophy and its modification by angiotensin II: current concepts. Basic Res Cardiol. 87 Suppl 2, 163-172 (1992).

- Friedrich, S. P., et al. Intracardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition improves diastolic function in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy due to aortic stenosis. Circulation. 90, 2761-2771 (1994).

- Rosker, C., Salvarani, N., Schmutz, S., Grand, T., Rohr, S. Abolishing myofibroblast arrhythmogeneicity by pharmacological ablation of alpha-smooth muscle actin containing stress fibers. Circ Res. 109, 1120-1131 (2011).

- Yue, L., Xie, J., Nattel, S. Molecular determinants of cardiac fibroblast electrical function and therapeutic implications for atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 89, 744-753 (2011).

- Rohr, S. Myofibroblasts in diseased hearts: new players in cardiac arrhythmias? Heart Rhythm. 6, 848-856 (2009).

- Coen, M., Gabbiani, G., Bochaton-Piallat, M. L. Myofibroblast-mediated adventitial remodeling: an underestimated player in arterial pathology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 31, 2391-2396 (2011).

- Brilla, C. G., Janicki, J. S., Weber, K. T. Cardioreparative effects of lisinopril in rats with genetic hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 83, 1771-1779 (1991).

- Youn, H. J., et al. Relation between flow reserve capacity of penetrating intramyocardial coronary arteries and myocardial fibrosis in hypertension: study using transthoracic Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 19, 373-378 (2006).

- Warnes, C. A., Maron, B. J., Roberts, W. C. Massive cardiac ventricular scarring in first-degree relatives with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 54, 1377-1379 (1984).

- Maron, B. J., Wolfson, J. K., Epstein, S. E., Roberts, W. C. Intramural ('small vessel') coronary artery disease in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 8, 545-557 (1986).

- Olivotto, I., et al. Microvascular function is selectively impaired in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and sarcomere myofilament gene mutations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 58, 839-848 (2011).

- Beltrami, C. A., et al. Structural basis of end-stage failure in ischemic cardiomyopathy in humans. Circulation. 89, 151-163 (1994).

- Factor, S. M., et al. Pathologic fibrosis and matrix connective tissue in the subaortic myocardium of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 17, 1343-1351 (1991).

- Waller, T. A., Hiser, W. L., Capehart, J. E., Roberts, W. C. Comparison of clinical and morphologic cardiac findings in patients having cardiac transplantation for ischemic cardiomyopathy, idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, and dilated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 81, 884-894 (1998).

- Schaper, J., Lorenz-Meyer, S., Suzuki, K. The role of apoptosis in dilated cardiomyopathy. Herz. 24, 219-224 (1999).

- de Leeuw, N., et al. Histopathologic findings in explanted heart tissue from patients with end-stage idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Transpl Int. 14, 299-306 (2001).

- Yoshikane, H., et al. Collagen in dilated cardiomyopathy--scanning electron microscopic and immunohistochemical observations. Jpn Circ J. 56, 899-910 (1992).

- Marijianowski, M. M., Teeling, P., Mann, J., Becker, A. E. Dilated cardiomyopathy is associated with an increase in the type I/type III collagen ratio: a quantitative assessment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 25, 1263-1272 (1995).

- Pearlman, E. S., Weber, K. T., Janicki, J. S., Pietra, G. G., Fishman, A. P. Muscle fiber orientation and connective tissue content in the hypertrophied human heart. Lab Invest. 46, 158-164 (1982).

- Huysman, J. A., Vliegen, H. W., Van der Laarse, A., Eulderink, F. Changes in nonmyocyte tissue composition associated with pressure overload of hypertrophic human hearts. Pathol Res Pract. 184, 577-581 (1989).

- Rossi, M. A. Pathologic fibrosis and connective tissue matrix in left ventricular hypertrophy due to chronic arterial hypertension in humans. J Hypertens. 16, 1031-1041 (1998).

- Lopez, B., Gonzalez, A., Querejeta, R., Larman, M., Diez, J. Alterations in the pattern of collagen deposition may contribute to the deterioration of systolic function in hypertensive patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 48, 89-96 (2006).

- Krayenbuehl, H. P., et al. Left ventricular myocardial structure in aortic valve disease before, intermediate, and late after aortic valve replacement. Circulation. 79, 744-755 (1989).

- Schwarz, F., et al. Myocardial structure and function in patients with aortic valve disease and their relation to postoperative results. Am J Cardiol. 41, 661-669 (1978).

- Hein, S., et al. Progression from compensated hypertrophy to failure in the pressure-overloaded human heart: structural deterioration and compensatory mechanisms. Circulation. 107, 984-991 (2003).

- Brooks, W. W., Shen, S. S., Conrad, C. H., Goldstein, R. H., Bing, O. H. Transition from compensated hypertrophy to systolic heart failure in the spontaneously hypertensive rat: Structure, function, and transcript analysis. Genomics. 95, 84-92 (2010).

- O'Hanlon, R., et al. Prognostic significance of myocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 56, 867-874 (2010).

- Green, J. J., Berger, J. S., Kramer, C. M., Salerno, M. Prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement in clinical outcomes for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 5, 370-377 (2012).

- Frankel, K. A., Rosser, R. J. The pathology of the heart in progressive muscular dystrophy: epimyocardial fibrosis. Hum Pathol. 7, 375-386 (1976).

- Otto, R. K., Ferguson, M. R., Friedman, S. D. Cardiac MRI in muscular dystrophy: an overview and future directions. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 23, 123-132 (2012).

- Finsterer, J., Stollberger, C. The heart in human dystrophinopathies. Cardiology. 99, 1-19 (2003).

- Galindo, C. L., et al. Anti-remodeling and anti-fibrotic effects of the neuregulin-1beta glial growth factor 2 in a large animal model of heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 3, e000773(2014).

- Caulfield, J. B., Borg, T. K. The collagen network of the heart. Lab Invest. 40, 364-372 (1979).

- Ohtani, O. Three-dimensional organization of the connective tissue fibers of the human pancreas: a scanning electron microscopic study of NaOH treated-tissues. Arch Histol Jpn. 50, 557-566 (1987).

- Rossi, M. A., Abreu, M. A., Santoro, L. B. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Connective tissue skeleton of the human heart: a demonstration by cell-maceration scanning electron microscope method. Circulation. 97, 934-935 (1998).

- Icardo, J. M., Colvee, E. Collagenous skeleton of the human mitral papillary muscle. Anat Rec. 252, 509-518 (1998).

- McGreevy, J. W., Hakim, C. H., McIntosh, M. A., Duan, D. Animal models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: from basic mechanisms to gene therapy. Dis Model Mech. 8, 195-213 (2015).

- Buckberg, G., Hoffman, J. I., Mahajan, A., Saleh, S., Coghlan, C. Cardiac mechanics revisited: the relationship of cardiac architecture to ventricular function. Circulation. 118, 2571-2587 (2008).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionExplore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved