Piaget's Conservation Task and the Influence of Task Demands

Overview

Source: Laboratories of Judith Danovitch and Nicholaus Noles—University of Louisville

Jean Piaget was a pioneer in the field of developmental psychology, and his theory of cognitive development is one of the most well-known psychological theories. At the heart of Piaget’s theory is the idea that children’s ways of thinking change over the course of childhood. Piaget provided evidence for these changes by comparing how children of different ages responded to questions and problems that he designed.

Piaget believed that at age 5, children lack mental operators or logical rules, which underlie the ability to reason about relationships between sets of properties. This characteristic defined what he called the preoperational stage of cognitive development. One of Piaget’s classic measures of children’s ability to use mental operations is his conservation task. In this task, children are shown two identical objects or sets of objects. Children are first shown that the objects are the same on one key property (number, size, volume, etc.). Then, one of the objects is modified so it appears different than the other one (e.g., it is now longer, wider, or taller), but the key property remains the same. Following this transformation, children are asked to judge if the two objects or sets of objects are now the same or different with respect to the original key property.

Piaget reported that children in the preoperational stage (approximately ages 2-7) typically judged the objects to be different after the transformation, even though the key property had not changed. He attributed children’s incorrect responses to their excessive focus on the change, rather than on the fact that the key property remained the same. However, over the years, researchers have argued that Piaget’s conservation task is an invalid measure of children’s reasoning skills. These critics have suggested that children’s poor performance is due to task demands, such as assumptions about the experimenter’s goals and expectations when the question about the key property is repeated.

This video demonstrates how to conduct Piaget’s classic conservation task,1–2 and how a small modification in the task design can dramatically change children’s accuracy (based on the methods developed by McGarrigle and Donaldson3).

Procedure

Recruit 4- to 6-year-old children who have normal vision and hearing. For the purposes of this demonstration, only two children are tested (one for each condition). Larger sample sizes are recommended when conducting any experiments.

1. Gather the necessary materials.

- Obtain two sets of four small tokens. For this experiment, use four red checkers and four blue checkers.

- Obtain two 10 in (25.4 cm) pieces of string or yarn of different colors. For this experiment, use blue and white yarn.

- Acquire a stuffed animal that fits in a box. For this experiment, use a teddy bear.

2. Data collection

- Introduction

- Place the teddy bear in the box on the table before the child enters the room.

- Seat the child at the table across from the experimenter.

- Remove the teddy bear from the box, show it to the child, and say: “This is a very naughty bear. Sometimes he escapes from his box and messes up the game. He likes to spoil the game.”

- Initial judgment of number

- Set up the tokens so they are in two rows of equal length, where the tokens are evenly spaced and there is a one-to-one correspondence between the rows. Make sure each row contains the same color tokens.

- Point to each row and ask the child: “Is there more here or more here, or do they both have the same number?” Record the child’s response.

- Alternate the location of the red and blue rows of tokens (closer or farther from the child) between subjects.

- Transformation

- At this point, randomly assign children to one of two conditions.

- In the intentional condition, direct the child’s attention to the tokens by saying, “Now, watch me,” and move the row of tokens that is further away from the child into a cluster closer together, so they touch.

- In the accidental condition, act surprised and say: “Oh, no, it’s the naughty bear. Look out! He is going to spoil the game!” Remove the bear from the box and use his hands to rearrange the row of tokens furthest from the child into a cluster closer together, so they touch. Then ask the child to return the bear to his box.

- Post-transformation judgment of number

- Point to each row of tokens and ask the child: “Is there more here or more here, or do they both have the same number?”

- Put away the tokens.

- Judgments of length

- Repeat the exact procedure just described for judgments of length.

- In these trials, initially place both strings on the table so they are straight and parallel to each other. The transformation involves pulling on the middle of one string so it is curved.

- Assign the children to the same condition for the judgment of length trials as they were for the judgment of number trials.

- At this point, randomly assign children to one of two conditions.

3. Analysis

- Exclude any children who answered the initial judgment questions incorrectly, as this suggests the children could not accurately judge number or length equivalence before the objects were transformed.

- Calculate a score of 0-2 for the number of times children in each condition judged the number or length of the objects stayed the same.

- Compare children’s scores across conditions using an independent samples t-test.

Results

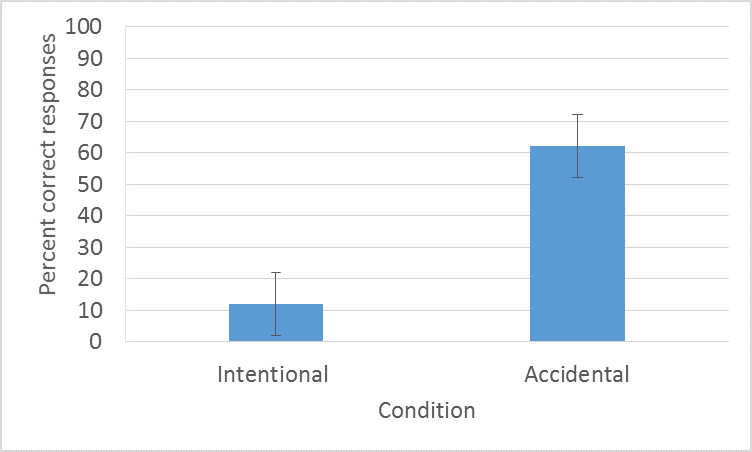

Researchers tested 20 4- through 6-year-old children and found that children in the accidental condition were much more likely to judge the number or length of the objects had stayed the same after the transformation (Figure 1). Children in the intentional condition performed very poorly (12% correct responses) compared to children in the accidental condition (62% correct). The intentional condition in this study corresponds to Piaget’s original method for the conservation task. Thus, this pattern of results suggests that children are more likely to pass Piaget’s conservation task when the task is framed in terms of an accidental transformation, rather than an intentional one. However, it is notable that even in the accidental condition, children in this age range still had some difficulty discerning the correct answer.

Why do children find it easier to judge that the two sets of objects remain the same when they have been rearranged by a naughty bear than when the experimenter rearranged them? One explanation is that children interpret the question differently in each condition. In the intentional condition, when the experimenter deliberately moved the object and then repeated the initial question, children may have assumed the experimenter was now referring to the dimension that was manipulated (e.g., area covered by the tokens) rather than the key property, and this led them to answer incorrectly. However, in the accidental condition, children had no reason to think the experimenter intended to change anything, and therefore they focused on the key property and answered correctly.

Figure 1: Mean percentage of trials in the accidental and intentional conditions where children judged the key property was the same after the transformation.

Application and Summary

This demonstration illustrates how task demands can affect the outcomes of psychological research, particularly in young children. The assumptions children make when an adult is talking to them and asking difficult questions may not always be obvious, but they can have a major influence on how children respond. This finding is important not only for researchers, but also for educators, parents, and other people who may be in situations where they are measuring a child’s skills or questioning a child about an event.

The manipulation demonstrated is only one example of many manipulations that have been shown to alter children’s performance on the conservation task. Despite the shortcomings of his original methods, Piaget’s proposal that children’s logic and reasoning skills change over development still has ample research support, and his ideas remain widely studied. If anything, this demonstration shows the value of collecting converging evidence across different labs and different populations of children.

References

- Piaget, J. The Child’s Conception of Number. Routledge and Kegan Paul. London, England (1952).

- Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. The Psychology of the Child. Basic Books. New York, New York (1969).

- McGarrigle, J., & Donaldson, M. Conservation accidents. Cognition. 3 (4), 341-350 (1975).

Skip to...

Videos from this collection:

Now Playing

Piaget's Conservation Task and the Influence of Task Demands

Developmental Psychology

61.2K Views

Habituation: Studying Infants Before They Can Talk

Developmental Psychology

54.1K Views

Using Your Head: Measuring Infants' Rational Imitation of Actions

Developmental Psychology

10.2K Views

The Rouge Test: Searching for a Sense of Self

Developmental Psychology

54.2K Views

Numerical Cognition: More or Less

Developmental Psychology

15.0K Views

Mutual Exclusivity: How Children Learn the Meanings of Words

Developmental Psychology

32.9K Views

How Children Solve Problems Using Causal Reasoning

Developmental Psychology

13.1K Views

Metacognitive Development: How Children Estimate Their Memory

Developmental Psychology

10.4K Views

Executive Function and the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task

Developmental Psychology

15.0K Views

Categories and Inductive Inferences

Developmental Psychology

5.3K Views

The Costs and Benefits of Natural Pedagogy

Developmental Psychology

5.2K Views

Children's Reliance on Artist Intentions When Identifying Pictures

Developmental Psychology

5.6K Views

Measuring Children's Trust in Testimony

Developmental Psychology

6.3K Views

Are You Smart or Hardworking? How Praise Influences Children's Motivation

Developmental Psychology

14.3K Views

Memory Development: Demonstrating How Repeated Questioning Leads to False Memories

Developmental Psychology

10.9K Views

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved