Method Article

Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve Replacement from Autologous Pericardium with a Self-Expandable Nitinol Stent in an Adult Sheep Model

In This Article

Summary

This study demonstrates the feasibility and safety of developing an autologous pulmonary valve for implantation at the native pulmonary valve position by using a self-expandable Nitinol stent in an adult sheep model. This is a step toward developing transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement for patients with right ventricular outflow tract dysfunction.

Abstract

Transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement has been established as a viable alternative approach for patients suffering from right ventricular outflow tract or bioprosthetic valve dysfunction, with excellent early and late clinical outcomes. However, clinical challenges such as stented heart valve deterioration, coronary occlusion, endocarditis, and other complications must be addressed for lifetime application, particularly in pediatric patients. To facilitate the development of a lifelong solution for patients, transcatheter autologous pulmonary valve replacement was performed in an adult sheep model. The autologous pericardium was harvested from the sheep via left anterolateral minithoracotomy under general anesthesia with ventilation. The pericardium was placed on a 3D shaping heart valve model for non-toxic cross-linking for 2 days and 21 h. Intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) and angiography were performed to assess the position, morphology, function, and dimensions of the native pulmonary valve (NPV). After trimming, the crosslinked pericardium was sewn onto a self-expandable Nitinol stent and crimped into a self-designed delivery system. The autologous pulmonary valve (APV) was implanted at the NPV position via left jugular vein catheterization. ICE and angiography were repeated to evaluate the position, morphology, function, and dimensions of the APV. An APV was successfully implanted in sheep J. In this paper, sheep J was selected to obtain representative results. A 30 mm APV with a Nitinol stent was accurately implanted at the NPV position without any significant hemodynamic change. There was no paravalvular leak, no new pulmonary valve insufficiency, or stented pulmonary valve migration. This study demonstrated the feasibility and safety, in a long-time follow-up, of developing an APV for implantation at the NPV position with a self-expandable Nitinol stent via jugular vein catheterization in an adult sheep model.

Introduction

Bonhoeffer et al.1 marked the beginning of transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement (TPVR) in 2000 as a rapid innovation with significant progress toward minimizing complications and providing an alternative therapeutic approach. Since then, the use of TPVR for treating the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) or bioprosthetic valve dysfunction has increased rapidly2,3. To date, the TPVR devices currently available on the market have provided satisfying long-term and short-term results for patients with RVOT dysfunction4,5,6. Furthermore, various types of TPVR valves including decellularized heart valves and stem cell-driven heart valves are being developed and evaluated, and their feasibility has been demonstrated in preclinical large animal models7,8. Aortic valve reconstruction using an autologous pericardium was first reported by Dr. Duran, for which three consecutive bulges of different sizes were used as templates to guide the shaping of the pericardium according to the dimensions of the aortic annulus, with the survival rate of 84.53% at the follow-up of 60 months9. The Ozaki procedure, which is considered a valve repair procedure rather than a valve replacement procedure, involves replacing aortic valve leaflets with the glutaraldehyde-treated autologous pericardium; however, when compared to Dr. Duran's procedure, it improved significantly in measuring the diseased valve with a template to cut fixed pericardium10 and satisfactory results were not only achieved from the adult cases but also pediatric cases11. Currently, only the Ross procedure can provide a living valve substitute for the patient who has a diseased aortic valve with obvious advantages in terms of avoiding long-term anticoagulation, growth potential, and low risk of endocarditis12. But re-interventions may be required for the pulmonary autograft and right ventricle to pulmonary artery conduit after such a complex surgical procedure.

The current bioprosthetic valves that are available for clinical use inevitably degrade over time due to graft-versus-host reactions to the xenogeneic porcine or bovine tissues13. Valve-related calcification, degradation, and insufficiency could necessitate repeated interventions after several years, especially in young patients who would need to undergo multiple pulmonary valve replacements in their lifetime due to the lack of growth of the valves, a property inherent to current bioprosthetic materials14. Furthermore, the currently available, essentially non-regenerative, TPVR valves have major limitations such as thromboembolic and bleeding complications, as well as limited durability due to adverse tissue remodeling which could lead to leaflet retraction and universal valvular dysfunction15,16.

It is hypothesized that developing a native-like autologous pulmonary valve (APV) mounted onto a self-expandable Nitinol stent for TPVR with the characteristics of self-repair, regeneration, and growth capacity would ensure physiological performance and long-term functionality. And the non-toxic crosslinker treated autologous pericardium can awake from the harvesting and manufacturing procedures. To this end, this preclinical trial was conducted to implant a stented autologous pulmonary valve in an adult sheep model with the aim of developing ideal interventional valvular substitutes and a low-risk procedural methodology to improve the transcatheter therapy of RVOT dysfunction. In this paper, sheep J was selected to illustrate the comprehensive TPVR procedure including pericardiectomy and trans jugular vein implantation of an autologous heart valve.

Protocol

This preclinical study approved by the legal and ethical committee of the Regional Office for Health and Social Affairs, Berlin (LAGeSo). All animals (Ovis aries) received humane care in compliance with the guidelines of the European and German Laboratory Animal Science Societies (FELASA, GV-SOLAS). The procedure is illustrated by performing autologous pulmonary valve replacement in a 3-year-old, 47 kg, female sheep J.

1. Preoperative management

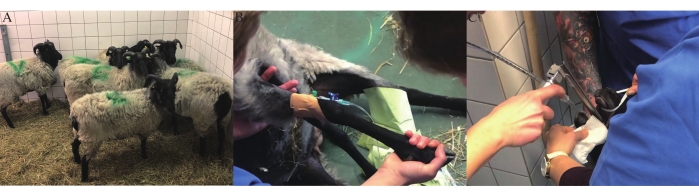

- House all experimental sheep in the same room containing straw for 1 week from the day of arrival to the pericardiectomy day to maintain social companionship (Figure 1A).

- Deprive the sheep of food but not water for 12 h prior to the pericardiectomy and implantation.

- Pre-medicate the sheep with an intramuscular injection of midazolam (0.4 mg/kg), butorphanol (0.4 mg/kg), and glycopyrrolate (0.011 mg/kg or 200 mcg) 20 min before intubation.

2. Induction of general anesthesia

- Aseptically place an 18 G safety intravenous (IV) catheter, an injection port, and a T port in the cephalic vein (Figure 1B).

- Induce anesthesia by intravenous injection of propofol (20 mg/mL, 1–2.5 mg/kg) and fentanyl (0.01 mg/kg) to effect.

- Indications of an adequate level of sedation include jaw relaxation, loss of swallowing, and papillary reflex. After sedation, intubate the sheep with an appropriately sized endotracheal tube (Figure 1C). Shave the sheep and then transfer it to the operating room (OR).

3. Intra-operative anesthesia management for pericardiectomy and implantation

- Use a pressure-cycled mechanical ventilator to initiate intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV) with 100% oxygen in the OR.

- Connect the sheep to the anesthetic device platform and ventilate the sheep throughout the anesthesia under pressure mode (tidal volume (TV) = 8-12 mL/kg, respiratory frequency (RF) = 12-14 breaths/min). Adjust the TV and RF to keep the end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) between 35-45 mmHg and the arterial partial pressure of CO2 (PaCO2) below 50 mmHg.

- Maintain anesthesia combined with isoflurane (to effect, suggested maintenance concentration 1.5%-2.5%) in oxygen with a flow rate of 1 L/min (inspired fraction of oxygen (FiO2) = 75%), combined with a continuous rate infusion (CRI) of fentanyl (5-15 mcg/kg/h) and midazolam (0.2-0.5 mg/kg/h).

- Place an 18 G safety IV catheter in the auricular artery for the measurement of invasive blood pressure (IBP).

- Connect the sheep to the multi-function anesthesia platform for hemodynamic monitoring, which displays the direct measurement of invasive blood pressure (IBP) in the auricular artery (zeroed at the level of the heart), body temperature with a rectal probe, a lead-IV electrocardiogram, plethysmographic oxygen saturation (SpO2), TV, RF, EtCO2, heart rate (HR), and FiO2.

- Position a gastric tube to evacuate excess gas and fluids from the reticulorumen in preparation for the pericardiectomy. Equip the gastric tube with a marker guide wire as a reference for the implantation.

- Place a foley urinary catheter via the urethra inside the bladder connected to a urine bag. Distend the foley balloon with a minimum of 5 mL of saline solution (0.9% NaCl).

- Carry out an activated coagulation test (ACT: 240-300 s) 30 min before implantation to confirm sufficient heparinization before and antagonization after the implantation. Perform arterial blood gas analysis (ABGs) to analyze the internal environment 30 min prior to pericardiectomy and implantation and every hour during the two procedures.

- Administer the following antibiotics, namely, sulbactam/ampicillin (20mg/kg) 30 min via intravenous drip prior to pericardiectomy and implantation. Ensure a continuous infusion of crystalloids (5 mL/kg/h, isotonic balanced electrolyte solution) and hydroxyethyl starch (HES, 30 mL/h) throughout the pericardiectomy and implantation.

4. Pericardiectomy

- Preparation for pericardiectomy

- Place the sheep on the operating table in the right lateral recumbent position with 30° elevation on the left side, and then secure her limbs with harnesses and straps.

- Sterilize the surgical site (pericardiectomy: superiorly to the left clavicle, anteriorly to the sternum, inferiorly to the level of the diaphragm, and posteriorly to the left midclavicular line) with chlorhexidine-alcohol before performing the minithoracotomy. Cover the remaining areas with sterile draping (Figure 2A).

- Make a 5 cm skin incision at the fourth intercostal parasternal position using a #10 surgical blade under general anesthesia.

- Dissect the pectoralis major- pectoralis minor- anterior serratus-intercostal muscle via the left lateral minithoracotomy (m-LLT) into 5 cm incisions in length consecutively and separately in the third and fourth intercostal space for ideal exposure (Figure 2B).

- Make the incision at least 2 cm offset from the sternum to prevent injury to the left internal thoracic artery and veins. Cease the ventilator for 10 s to prevent lung injury before opening the thorax.

- Use several sterile gauzes to compress the left lung for better exposure of the surgical field after placing a rib spreader (Figure 2C). Visualize the pericardium and thymus in the surgical field (Figure 2D).

- Start the pericardiectomy at the attachment point of the pericardium and diaphragm and harvest the pericardial tissue between the two phrenic nerves, up to the innominate veins, down to the diaphragm.

- Compress the left lung as mentioned in step 4.1.5 to expose the attachment of the diaphragm-pericardium-mediastinal pleura. Cut open the left mediastinal pleura at the attachment of the diaphragm-pericardium-mediastinal pleura by making a 1 cm incision in length using a surgical scissor. Extend the incision upward into the innominate veins along the line which is 1 cm offset from the left phrenic nerve (Figure 2E).

- Repeat the procedure for the right part of the pericardium by elevating the apex to the left using fingers. Dissect the thymic and pericardial fat from the sternum.

- Meet the two incisions of the pericardium in front of the aorta. Cross clamp the intersection of pericardium and thymus from the two pericardial incisions in front of the aorta by holding them firmly in place and tying six surgical knots manually using a 4-0 non-resorbable suture.

- Avoid injury of the phrenic nerve and the underlying vascular structures, when harvesting the pericardium. Dissect adipose tissue including the thymus from the surface of the pericardium during pericardiectomy. Use a cautery tool (i.e., electrotome, Bovie) for hemostasis.

- Place the harvested pericardium onto the sterile plate with a centimeter scale to remove the extra adipose tissue, and then wash it twice in 0.9% NaCl (Figure 2F). Double-check all the surgical areas for hemostasis.

- Suture the opened right mediastinal pleura to the residual right pericardial edge with 3-0 polydioxanone in a running fashion twice. Inflate the right lung to the largest volume manually using a breathing bag and hold for 10 s prior to closing the right thorax. Suture the opened left mediastinal pleura to the residual left pericardial edge with 3-0 polydioxanone in a running fashion twice.

- Close the left thoracic incisions in four layers as described below.

- Suture the intercostal muscles and anterior serratus with 2- 0 polydioxanone in a simple interrupted or cruciate fashion, pectoralis major-pectoralis minor with 3-0 polydioxanone in a running fashion, the subcutis with 3-0 polydioxanone in a cruciate fashion, and the skin with 3-0 nylon in a simple interrupted fashion. Place all the sutures at 1 cm intervals.

- Inflate the left lung to the largest volume manually using a breathing balloon and hold for 10 s prior to closing the intercostal muscles.

- Cover the incision with sterile gauze and compress it manually for 5 min to prevent hemorrhage after heparinization for the new heart valve implantation. Then bandage the surgical site.

- Stop the intravenous anesthetics and isoflurane when performing the skin suture to reduce the depth of sedation.

- Remove the gastric tube and urinary catheter after the spontaneous respiration returns. Then transfer the sheep with pulse oximetry to the recovery room on the stretcher.

- Remove the endotracheal tube when the swallowing reflex, the papillary reflex, and normal spontaneous breathing recover. Administer 0.5 mg/kg meloxicam subcutaneously once a day before the implantation.

- Once the anesthesia is completely reversed (i.e., when the sheep is able to stand independently), the sheep can be given access to food and water.

5. Preparation of the three-dimensional autologous heart valve

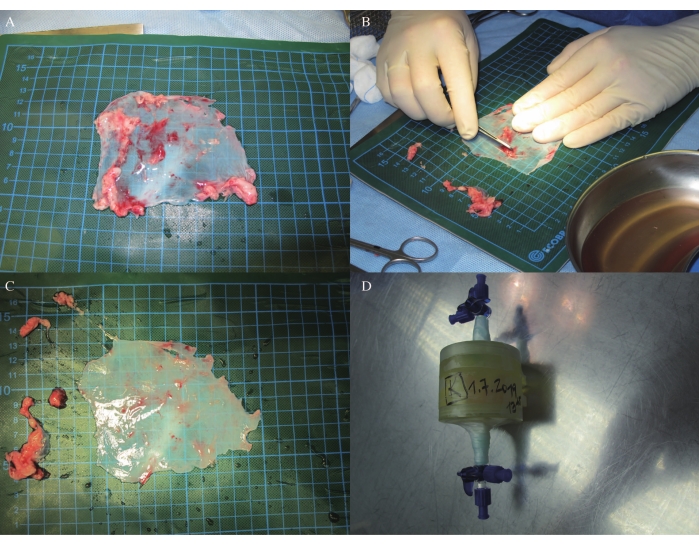

- Trim the pericardium by removing the adipose tissue (Figure 3A,B,C), and then place it onto the 3D shaping heart valve mold. (Due to a pending patent application, figures cannot be provided in this step.)

- Put the pericardium and the 3D shaping heart valve model into an incubator with a non-toxic crosslinker (30 mL) for 2 days and 21 h (Figure 3D; due to the pending patent application, figures and detailed information of non-toxic crosslinker cannot be provided in this step).

6. Preparation of the APV

- Wash the crosslinked heart valve in 0.9% NaCl twice and suture it into a Nitinol stent (30 mm in diameter, 29.4 mm in height, 48 rhombic cells) in a discontinuous fashion after 2 days and 21 h. Use 5-0 polypropylene to suture the heart valve in place using six to eight knots to align the attachment points between the heart valve and stent. (Due to a patent application, figures cannot be provided in this step.)

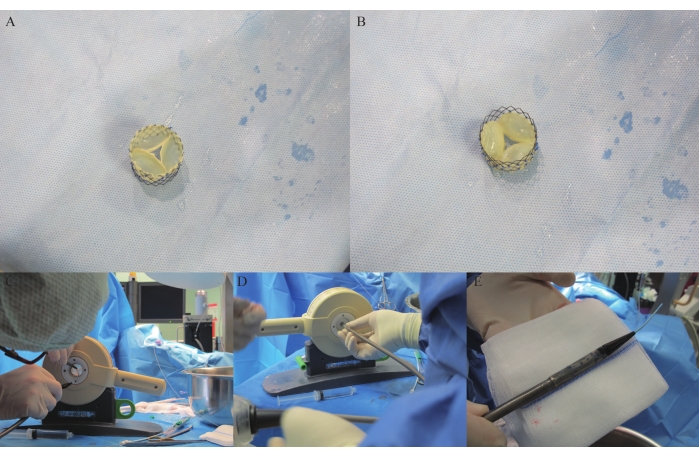

- Cut the three free edges of the autologous pulmonary valve open with a no. 15 surgical blade (Figure 4A,B). Hold the stented pulmonary valve with a surgical tweezer, lift and leave the APV in 0.9% NaCl to test its opening and closing and to evaluate whether the three commissures need further cutting to achieve a larger opening of the orifice.

- Incubate the APV in an incubator for 30 min for sterilization in 47.6 mL of PBS with 0.8% amphotericin B (0.4 mL) and 4.0% penicillin/streptomycin (2 mL). Crimp the stented heart valve into the head of a delivery system (DS) using a commercial crimper for two-fold testing (Figure 4C-D) and fit it into the delivery system (Figure 4E).

7. Transcatheter autologous pulmonary valve implantation via the left jugular vein

- Anesthetize the sheep for APV implantation as illustrated in steps 1 to 3.

- Vessel access: Shave the sheep and sterilize the surgical field, which includes superiorly to the inferior border of the mandible, anteriorly to the anterior median line, inferiorly to the superior border of left clavicle, and posteriorly to the posterior median line using a povidone-iodine antiseptic before performing the implantation. Cover the remaining unshaved and unsterilized areas with sterile draping.

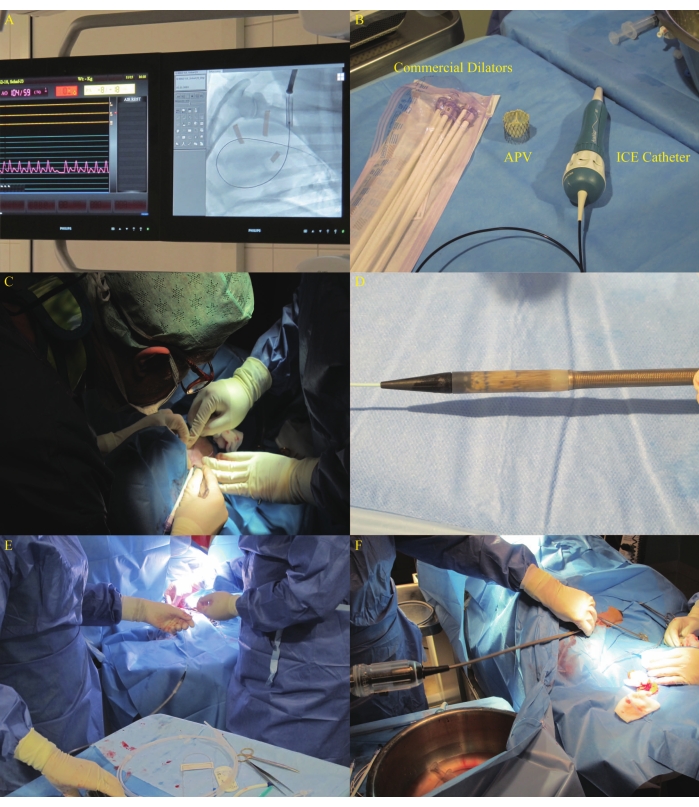

- Mark the left jugular vein on the neck and using the Seldinger technique place the guidewire into the left jugular vein. Enlarge the puncture point with a no. 10 blade, place a 11 F sheath into the left jugular vein for the ICE probe and delivery system (Figure 5A,B). Place a purse-string suture around the sheath introducer with a 4-0 non-absorbable suture.

- Intracardiac echocardiography (ICE)17

- Perform ICE before and immediately after the implantation using a 10 Fr ultrasound catheter (Figure 5C). Asses the parameters including the dimensions and functions of the NPV, APV, and tricuspid valve by 2D, color, pulsed wave, and continuous Doppler in the short and long axis.

- Evaluate the degree of valvular regurgitation in the vena contracta by semi-quantitative assessment18 via ICE (Figure 6).

- Angiography19: Perform angiography using a portable C-arm and a functional screen to guide the implantation by measuring the diameters of the RVOT, NPV, pulmonary bulb, and supravalvular pulmonary artery, as well as to evaluate the APV after implantation (Figure 7A-D).

- Hemodynamics20: Measure and record the right ventricular and pulmonary artery pressure before and after the implantation using a 5.2 F 145° pigtail catheter. Measure the systemic arterial pressure via the auricular artery.

- Implantation

- Establishment of the TPVR tract: Place a 0.035-inch angled guidewire to the right pulmonary artery under the guidance of fluoroscopy. Then, place a 5.2 Fr pigtail catheter into the left jugular vein and advance it into the right pulmonary artery with the guidance of the previously placed guidewire under fluoroscopy.

- Retrieve the angled guidewire out of the left jugular vein. Place a 5 Fr Berman angiographic balloon catheter into the left jugular vein and advance it into the right pulmonary artery using the guidance of the guidewire.

- Pre-shape the 0.035-inch ultra-stiff guidewire into a circle of about 8-10 cm in length with a diameter equaling the distance from the central point of the tricuspid valve to the central point of the pulmonary valve according to the fluoroscopy measurement and advance it into the right pulmonary artery under the guidance of the balloon catheter (Figure 8A). Ensure the wire does not interfere with the tricuspid valve chordae.

- Dilate the skin with a no. 11 blade and dilate the left jugular vein using commercial dilators from 16 Fr to 22 Fr sequentially (Figure 8B). Close the incision with a 3-0 polydioxanone purse-string suture after dilatation (Figure 8C). Perform angiography to ensure the desired position of the stent-bearing part of the DS as described in19.

- Mark the sinotubular junction of the pulmonary valve at the end-systolic and end-diastolic cardiac phases during pulmonary angiography as the distal border of the landing zone and the basal plane of the pulmonary valve as the proximal border of the landing zone.

- Reopen and inspect the stented autologous valve for crimping-induced damage. Re-crimp the APV and fit it into the head of the DS (Figure 8D). Advance the loaded DS via the pre-shaped guidewire through the right ventricular inflow tract (RVIT) and the RVOT to the NPV position (Figure 8E,F, and Figure 9A).

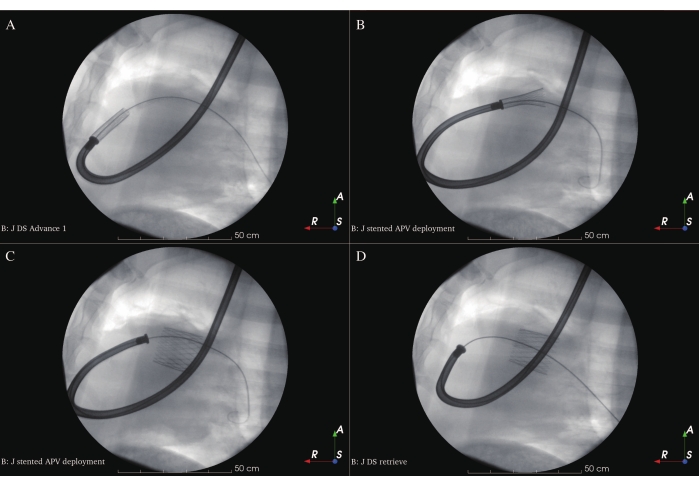

- Retract the cover tube of the DS and deploy the APV slowly and directly over the NPV in the landing zone at the end of the diastolic phase under fluoroscopic guidance (Figure 9A-C). Exercise caution when loaded DS is crossing the junction between the RVIT and the RVOT in order to prevent myocardial injury and ventricular fibrillation. The optimal position for the APV is when the middle part of the stent is placed onto the NPV.

- Retract the tip of the DS carefully into the cover tube after deployment and retrieve the DS from the sheep (Figure 9D). Repeat ICE (Figure 6D-F), angiography (Figure 7C-D), and hemodynamic measurements for post-examination of the dimensions and functions of the implanted APV. Close the incision on the left side of the neck with the pre-placed purse-string suture and compress it manually.

8. Peri-implantation medication

- Prior to implantation, administer the sheep with heparin at a dose of 5000 IU to maintain an activated clotting time (ACT) of 240-300 s. Use ACT tests throughout the procedure. Repeat ACT tests every 30 min after the start of the procedure to confirm both sufficient heparinization before and antagonization after the implantation.

- Before the APV implantation, administer 10% magnesium at a dose of 0.02 mol/L and amiodarone at a dose of 3-5 mg/kg to prevent cardiac arrhythmias.

- Administer sulbactam/ampicillin (20 mg/kg) intravenously to prevent infection and endocarditis at the start of the pericardiectomy and implantation procedure.

9. Postoperative management

- Perform a daily postoperative follow-up for 5 days, checking the general condition of the sheep in terms of heart rate and rhythm, breathing depth, breathing rhythm, and breath sound (for checking postoperative pneumonia), signs of pain, and other abnormalities. Check the wound for postoperative swelling, inflammation, redness, bleeding, and secretion.

- Continue anticoagulation for 5 days with dalteparin 5000 IU or another low-molecular-weight heparin administered subcutaneously once daily. Administer 1 mg/kg meloxicam by subcutaneous injection for postoperative analgesia for 5 days.

- Perform a laboratory blood test, including hematology, liver function, renal function, and serum chemistry to evaluate the sheep's physical condition.

10. Follow-up

- Perform ICE, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI), angiography, and record hemodynamics every 3-6 months after implantation for up to 21 months. Perform ICE and angiography as illustrated above.

- Perform cMRI to evaluate the regurgitation fraction (RF) on a 3.0 T MRI scanner using a standard electrocardiogram-gated cine-MRI method21. Perform final cardiac computed tomography (CT) to evaluate the stent position and the deformation of the right heart throughout the entire cardiac cycle as illustrated in our previous study22.

Results

In sheep J, the APV (30 mm in diameter) were successfully implanted in the "landing zone" of the RVOT.

In sheep J, the hemodynamics remained stable throughout the left anterolateral minithoracotomy under general anesthesia with ventilation, as well as in the follow-up MRI and ICE (Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3). Autologous pericardium measuring 9 cm x 9 cm was harvested and trimmed by removing extra tissue (Figure 3A-C). The autologous pericardium was placed onto the 3D shaping mold and crosslinked in an incubator with a non-toxic crosslinker for 2 days and 21 h (Figure 3D).

A Nitinol stent was mounted to the outside of the crosslinked pericardium, and 5-0 polypropylene sutures were used to sew the stent and heart valve together in a discontinuous fashion. The stented heart valve was then cut open (Figure 4A-H).

The APV was crimped into the head of a self-designed delivery system and advanced to the NPV position under the guidance of a stiff guidewire. The APV was successfully and fully deployed at the desired NPV position without any significant hemodynamic change (Figure 8A-D).

ICE and angiography assessment immediately after APV deployment showed no paravalvular leak, no new pulmonary valve insufficiency, or stented pulmonary valve migration of the APV (Figure 6D-F).

The implanted stent was anchored in the targeted position without migration forward to the pulmonary artery or backward to the RV, according to the final CT. Furthermore, blood flow in the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and left circumflex artery (LCX) was unaffected by the stent throughout the cardiac cycle (Figure 10).

The implanted stented APV demonstrated favorable function and hemodynamics in the right cardiac system with a 5%-10% regurgitation fraction in the follow-up MRI and ICE (Table 3).

Figure 1: Animal preparation. (A) Sheep for preclinical study. (B) IV catheter placement in the cephalic vein. (C) Orotracheal intubation. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Pericardiectomy procedure. (A) The surgical field. (B) Surgical mark in the third/fourth intercostal space. (C) Rib retractor placement for exposure. (D) Exposure of pericardium and thymus. (E) Pericardiectomy. (F) Harvested pericardium. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Pericardial trimming and crosslinking. (A-C) Pericardial trimming. (D) Pericardial crosslinking in an incubator. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: APV stenting and loading in DS. (A) Stented APV viewed from the pulmonary artery. (B) Stented APV viewed from the RVOT. (C-D) Stented APV being crimped in the crimper. (E) Crimped stented APV in the delivery system. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5: TPVR access establishment via the left jugular vein. (A-B) Sheath placement for ICE probe and delivery system via the left jugular vein. (C) ICE evaluation via the left jugular vein. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 6: Pre- and post-implantation ICE evaluations. (A) Native pulmonary valve sizing. (B) Native pulmonary valve function. (C) Native pulmonary valve velocity, pressure gradient (PG), and velocity time integral (VTI). (D) Autologous pulmonary valve sizing. (E) Autologous pulmonary valve function. (F) Autologous pulmonary valve velocity, pressure gradient (PG), and velocity time integral (VTI). Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 7: Pre- and post-implantation angiography. (A) Right ventricular and pulmonary artery angiography prior to implantation. (B) Pulmonary artery angiography prior to implantation. (C) Right ventricular and pulmonary artery angiography post-implantation. (D) Pulmonary artery angiography post-implantation. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 8: DS advancement via the left jugular vein. (A) Guidewire placement in the right pulmonary artery. (B) Commercial dilators used in the study. (C) Incision dilatation using dilators in the left jugular vein. (D) Recrimped APV that was fitted into the head of the DS. (E-F) DS advancement. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 9: Stented APV deployment. (A) Loaded DS at the deployment position. (B) Stented APV deployment at the beginning. (C) Stented APV total deployment. (D) Retrieval of DS. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 10: Relationship between the stented pulmonary artery and left coronary artery throughout the cardiac cycle. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| ABP (mmHg) | Mean ABP (mmHg) | HR (/ min) | SpO2 (%) | |

| Pre- Implantation | 129/104 | 115 | 98 | 98 |

| Post-Implantation | 113/89 | 98 | 93 | 97 |

Table 1: Hemodynamics during pericardiectomy. The arterial pressure, heart rate, and SpO2 of Sheep J during pericardiectomy remained stable.

| ABP (mmHg) | Mean ABP (mmHg) | RVP (mmHg) | Mean RVP (mmHg) | PaP (mmHg) | Mean PaP (mmHg) | HR (/ min) | |

| Pre- Implantation | 108/61 | 74 | 11/ -7 | 0 | 13/0 | 3 | 70 |

| Post-Implantation | 116/69 | 84 | 13/-9 | -3 | 10/-6 | 1 | 67 |

Table 2: Hemodynamics during implantation. The arterial pressure, pulmonary pressure, heart rate and SpO2 of Sheep J during implantation remained stable.

| MRI- Regurgitant fraction (%) | Right ventricular pressure (mean) (mmHg) | Pulmonary artery pressure (mean) (mmHg) | Systematic aeterial pressure | |

| Pre- implantation | - | 11/-7 (0) | 13/0 (3) | 108/61 (74) |

| Post- implantation | - | 13/-9 (-3) | 10/-6 (1) | 116/69 (84) |

| Follow-up 4 months | 5 | - | - | - |

| Follow-up 7 months | 7 | 27/4 (11) | 23/11 (16) | - |

| Follow-up 10 months | 5 | - | - | - |

| Follow-up 15 months | 7 | 26/-2 (12) | 23/15 (18) | - |

| Follow-up 18 months | 10 | 26/12 (14) | 23/18 (20) | - |

| Follow-up 21 months | 6 | 20/-8 (16) | 19/6 (11) | - |

| ICE (PV) | PV Vmax (m/s) | PV maxPG (mmHg) | PV meanPG (mmHg) | PR Vmax (m/s) | PR EROA (cm²) | PR Regurgitation volume (mL) |

| Pre- implantation | 0.71 | 2.01 | 1.06 | 0.76 | 0.25 | 1.7 |

| Post- implantation | 0.75 | 2.22 | 1.19 | 0.78 | 0.2 | 1 |

| Follow-up 4 months | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Follow-up 7 months | 0.8 | 2.58 | 1.12 | 0.94 | 0.2 | 3 |

| Follow-up 10 months | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Follow-up 15 months | 1.08 | 4.64 | 1.76 | - | 0.3 | 1 |

| Follow-up 18 months | 0.75 | 2.22 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.3 | 1 |

| Follow-up 21 months | 0.61 | 1.46 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.1 | 1 |

| PV: Pulmonary valve | PG: Pressure gradient | EROA: Effective regurgitation orifice area | PR: Pulmoanry regurgitation |

| ICE (TV) | TV Vmax (m/s) | TV maxPG (mmHg) | TV meanPG (mmHg) | TR Vmax (m/s) |

| Pre- implantation | - | - | - | - |

| Post- implantation | 0.56 | 1.27 | 0.48 | 0.83 |

| Follow-up 4 months | - | - | - | - |

| Follow-up 7 months | 0.99 | 3.92 | 1.68 | 0.84 |

| Follow-up 10 months | - | - | - | - |

| Follow-up 15 months | 0.95 | 3.6 | 1.47 | 1.04 |

| Follow-up 18 months | 0.95 | 3.6 | 1.47 | 1.03 |

| Follow-up 21 months | 0.94 | 3.56 | 1.31 | 0.95 |

| TV: Tricuspid valve |

Table 3: Follow-up data of MRI and ICE. A 21-month follow-up with MRI was done and the regurgitation fraction of autologous pulmonary valve from sheep J was found to be from 5% to 10%, which showed favorable valve function. The intracardiac echocardiography from sheep J showed that the autologous pulmonary valve only had 1 mL to 3 mL of regurgitation volume with normal tricuspid valve function.

Discussion

This study represents an important step forward in developing a living pulmonary valve for TPVR. In an adult sheep model, the method was able to show that an APV derived from the sheep's own pericardium can be implanted with a self-expandable Nitinol stent via jugular vein catheterization. In sheep J, the stented autologous pulmonary valve was successfully implanted in the correct pulmonary position using a self-designed universal delivery system. After implantation, the heart valve of sheep J showed good functionality for up to 21 months, serving not only as safe and efficient preclinical evidence for the future preclinical trial with an autologous pulmonary valve in immature sheep but also for translation to the clinical setting.

TPVR-AVP via jugular vein catheterization in an adult sheep model

Due to the anatomical and hemodynamic similarities with humans, adult sheep are one of the most popular and extensively used large animal models in numerous investigations evaluating the functionality and performance of bioprosthetic heart valves23,24. For catheterization and implantation, the transjugular venous approach is given preference over the transfemoral venous, which requires a larger profile of the delivery system and is associated with more difficult management during and after the implantation. The APV can be delivered via the SVC-right atrium-tricuspid valve-right ventricle to the pulmonary position with a shorter distance and a larger angle between the SVC-RA compared with the IVC-RA, which could make it easier to advance the loaded delivery system into the RV.

Pericardiectomy

Autologous 9 cm x 9 cm pericardium from sheep J was harvested without injury to the phrenic nerve and left internal thoracic artery and veins. The sheep did not suffer from diaphragmatic spasm, respiratory insufficiency, or bleeding complications after the minithoracotomy. Due to the narrow space between the ribs in sheep, it was difficult to achieve the desired exposure of the pericardium in the minithoracotomy, especially during the pericardiectomy. Therefore, caution should be taken during tissue dissection to avoid injury to the aortic and pulmonary roots, coronary artery, and phrenic nerve25. General anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane, fentanyl, and midazolam without muscle relaxants for early revival and stable hemodynamics. However, if the patients have had pericardiectomy and/or pericardiotomy during previous surgeries, there are limitations to performing thoracotomy to acquire the pericardium. First, it can lead to uncontrollable hemorrhage due to the sutures placed during the previous operations when mobilizing the pericardium in front of the ascending aorta, pulmonary trunk, coronary arteries as well as myocardium. In addition, the pericardium could not be enough for manufacturing an autologous heart valve, which needs at least 9 cm x 9 cm tissue size for a 30 mm diameter heart valve. Furthermore, the quality of the pericardium might not meet the requirement of the new stented heart valve. Even if the harvested pericardium is enough for one autologous heart valve, hemostasis in the surgical area is extremely difficult after the systematic heparinization prior to the TPVR. In these situations, rectus fascia, fascia Lata, and transversalis fascia could be candidates for harvesting the autologous tissue for the heart valve.

Implantation

Before loading the stented APV into the delivery system, it should be crimped in a commercial crimper for testing. The stent would elongate by up to 10% during crimping, which could lead to stress-related rupture at most suture points of the leaflets and the attachments of the commissures. In the sheep J, a 30 mm stented valve was tested and loaded into a 26 Fr delivery system using a crimper without rupture and suture loss. A small device (including the stented APV) and delivery system would be beneficial in terms of fitting the jugular vein, particularly for children. Miniaturization of the TPVR device would make for better perioperative safety in future transfemoral implantations.

Based on previous experience, the PV plane moved approximately 2 cm in every cardiac cycle, which presented a major challenge when deploying the APV in the correct position. In addition, the healthy sheep had no clear landmarks such as calcifications in the landing zone, which occurs commonly in the case of human patients, making accurate positioning difficult. Furthermore, due to the radial force, the self-expandable Nitinol stent jumped off the delivery system or even into the pulmonary artery when approximately 2/3 of the stent was uncovered as soon as the outer tube was withdrawn. Further refinements of the stent and delivery system with repositioning architectures are needed to better control the deployment in case of mispositioning and when withdrawing the stented APV into the tube. In sheep J, the APV was implanted in the correct position with the aid of the delivery system, which performed excellently without kinking or stent jumping.

Follow-up by MRI, ICE, and final CT

The implanted stented APV showed favorable valve function with 5%-10% regurgitation fraction on MRI, stable hemodynamics on ICE, and desired anchoring position with neighborly relations to left coronary artery throughout the entire cardiac cycle in the long-time follow-ups. Results of this study provided strong evidence of the stable macroscopical performance of a stented APV, which can bring benefit to the patients suffering from dysfunctional RVOT.

In large animal trials, valvular dysfunction has been proven by misreferred valve remodeling, which includes delamination, leaflet thickening, leaflet retraction, and irregularities26,27. According to the current International Organization of Standardization (ISO) standards for heart valve prostheses in a low-pressure circulation, heart valve regurgitation of up to 20% is acceptable. Considering the manufacturing process of an APV, the valve geometry with 3D shaping is the key factor for achieving a favorable outcome in this paper. In addition, the valve geometry, material properties, and hemodynamic loading conditions can determine valve functionality and remodeling26. The APV performed very closely to an NPV, with minimal valvular insufficiency assessed by ICE immediately after the implantation.

Conclusion

In the large animal study reported here, we aimed to create and test a method for transjugular vein implantation of an autologous pulmonary valve mounted onto a self-expandable Nitinol stent. An APV was successfully implanted in sheep J using this methodology and a self-designed delivery system. The APVs withstood the stress during crimping, loading, and deployment and achieved the desired valve functionality.

This study demonstrated the feasibility and safety in a long-time follow-up of developing an APV for implantation at the NPV position with a self-expandable Nitinol stent via jugular vein catheterization in an adult sheep model.

Limitations

This preclinical study presented many limitations that could not be fully addressed due to the small number of sheep. The Nitinol stent and the delivery system used in this study lacked architectures for repositioning; this would need to be refined for future animal trials. In addition, it would be interesting to evaluate the functionality of the APV beyond the study period to further investigate the performance and leaflet formation after at least 1 year of follow-up post-implantation. Moreover, the delivery system needs to be improved with a low profile and flexible trafficability characteristic to prevent arrhythmia and myocardial injury during the implantation. There is still a need to develop a biodegradable stent that enables APV growth in children to do away with the need for multiple heart valve replacements.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We extend our heartfelt appreciation to all who contributed to this work, both past and present members. This work was supported by grants from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, EXIST - Transfer of Research (03EFIBE103). Yimeng Hao is supported by the China Scholarship Council (CSC: 202008450028).

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 10 % Magnesium | Inresa Arzneimittel GmbH | PZN: 00091126 | 0.02 mol/ L, 10X10 ml |

| 10 Fr Ultrasound catheter | Siemens Healthcare GmbH | SKU 10043342RH | ACUSON AcuNav™ ultrasound catheter |

| 3D Slicer | Slicer | Slicer 4.13.0-2021-08-13 | Software: 3D Slicer image computing platform |

| Adobe Illustrator | Adobe | Adobe Illustrator 2021 | Software |

| Amiodarone | Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH | PZN: 4599382 | 3- 5 mg/ kg, 150 mg/ 3 ml |

| Amplatz ultra-stiff guidewire | COOK MEDICAL LLC, USA | Reference Part Number:THSF-35-145-AUS | 0.035 inch, 145 cm |

| Anesthetic device platform | Drägerwerk AG & Co. KGaA | 8621500 | Dräger Atlan A350 |

| ARROW Berman Angiographic Balloon Catheter | Teleflex Medical Europe Ltd | LOT: 16F16M0070 | 5Fr, 80cm (X) |

| Butorphanol | Richter Pharma AG | Vnr531943 | 0.4mg/kg |

| C-Arm | BV Pulsera, Philips Heathcare, Eindhoven, The Netherlands | CAN/CSA-C22.2 NO.601.1-M90 | Medical electral wquipment |

| Crimping tool | Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA | 9600CR | Crimper |

| CT | Siemens Healthcare GmbH | − | CT platform |

| Dilator | Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA | 9100DKSA | 14- 22 Fr |

| Ethicon Suture | Ethicon | LOT:MKH259 | 4- 0 smooth monophilic thread, non-resorbable |

| Ethicon Suture | Ethicon | LOT:DEE274 | 3-0, 45 cm |

| Fast cath hemostasis introducer | ST. JUDE MEDICAL Minnetonka MN | LOT Number: 3458297 | 11 Fr |

| Fentanyl | Janssen-Cilag Pharma GmbH | DE/H/1047/001-002 | 0.01mg/kg |

| Fragmin | Pfizer Pharma GmbH, Berlin, Germany | PZN: 5746520 | Dalteparin 5000 IU/ d |

| Functional screen | BV Pulsera, Philips Heathcare, Eindhoven, The Netherlands | System ID: 44350921 | Medical electral wquipment |

| Glycopyrroniumbromid | Accord Healthcare B.V | PZN11649123 | 0.011mg/kg |

| Guide Wire M | TERUMO COPORATION JAPAN | REF*GA35183M | 0.89 mm, 180 cm |

| Hemochron Celite ACT | International Technidyne Corporation, Edison, USA | NJ 08820-2419 | ACT |

| Heparin | Merckle GmbH | PZN: 3190573 | Heparin-Natrium 5.000 I.E./0,2 ml |

| Hydroxyethyl starch (Haes-steril 10 %) | Fresenius Kabi Deutschland GmbH | ATC Code: B05A | 500 ml, 30 ml/h |

| Imeron 400 MCT | Bracco Imaging | PZN00229978 | 2.0–2.5 ml/kg, Contrast agent |

| Isoflurane | CP-Pharma Handelsges. GmbH | ATCvet Code: QN01AB06 | 250 ml, MAC: 1 % |

| Jonosteril Infusionslösung | Fresenius Kabi Deutschland GmbH | PZN: 541612 | 1000 ml |

| Ketamine | Actavis Group PTC EHF | ART.-Nr. 799-762 | 2–5 mg/kg/h |

| Meloxicam | Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica GmbH | M21020A-09 | 20 mg/ mL, 50 ml |

| Midazolam | Hameln pharma plus GMBH | MIDAZ50100 | 0.4mg/kg |

| MRI | Philips Healthcare | − | Ingenia Elition X, 3.0T |

| Natriumchloride (NaCl) | B. Braun Melsungen AG | PZN /EAN:04499344 / 4030539077361 | 0.9 %, 500 ml |

| Pigtail catheter | Cordis, Miami Lakes, FL, USA | REF: 533-534A | 5.2 Fr 145 °, 110 cm |

| Propofol | B. Braun Melsungen AG | PZN 11164495 | 20mg/ml, 1–2.5 mg/kg |

| Propofol | B. Braun Melsungen AG | PZN 11164443 | 10mg/ml, 2.5–8.0 mg/kg/h |

| Safety IV Catheter with Injection port | B. Braun Melsungen AG | LOT: 20D03G8346 | 18 G Catheter with Injection port |

| Sulbactam- ampicillin | Pfizer Pharma GmbH, Berlin, Germany | PZN: 4843132 | 3 g, 2.000 mg/ 1.000 mg |

| Sulbactam/ ampicillin | Instituto Biochimico Italiano G Lorenzini S.p.A. – Via Fossignano 2, Aprilia (LT) – Italien | ATC Code: J01CR01 | 20 mg/kg, 2 g/1 g |

| Surgical Blade | Brinkmann Medical ein Unternehmen der Dr. Junghans Medical GmbH | PZN: 354844 | 15 # |

| Surgical Blade | Brinkmann Medical ein Unternehmen der Dr. Junghans Medical GmbH | PZN: 354844 | 11 # |

| Suture | Johnson & Johnson | Hersteller Artikel Nr. EH7284H | 5-0 polypropylene |

References

- Bonhoeffer, P., et al. Percutaneous replacement of pulmonary valve in a right-ventricle to pulmonary-artery prosthetic conduit with valve dysfunction. Lancet. 356 (9239), 1403-1405 (2000).

- Georgiev, S., et al. Munich comparative study: Prospective long-term outcome of the transcatheter melody valve versus surgical pulmonary bioprosthesis with up to 12 years of follow-up. Circulation. Cardiovascualar Interventions. 13 (7), 008963 (2020).

- Plessis, J., et al. Edwards SAPIEN transcatheter pulmonary valve implantation: Results from a French registry. JACC. Cardiovascular Interventions. 11 (19), 1909-1916 (2018).

- Bergersen, L., et al. Harmony feasibility trial: Acute and short-term outcomes with a self-expanding transcatheter pulmonary valve. JACC. Cardiovascular Interventions. 10 (17), 1763-1773 (2017).

- Cabalka, A. K., et al. Transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement using the melody valve for treatment of dysfunctional surgical bioprostheses: A multicenter study. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 155 (4), 1712-1724 (2018).

- Shahanavaz, S., et al. Transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement with the sapien prosthesis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 76 (24), 2847-2858 (2020).

- Motta, S. E., et al. Human cell-derived tissue-engineered heart valve with integrated Valsalva sinuses: towards native-like transcatheter pulmonary valve replacements. NPJ Regenerative Medicine. 4, 14 (2019).

- Uiterwijk, M., Vis, A., de Brouwer, I., van Urk, D., Kluin, J. A systematic evaluation on reporting quality of modern studies on pulmonary heart valve implantation in large animals. Interactive Cardiovascular Thoracic Surgery. 31 (4), 437-445 (2020).

- Duran, C. M., Gallo, R., Kumar, N. Aortic valve replacement with autologous pericardium: surgical technique. Journal of Cardiac Surgery. 10 (1), 1-9 (1995).

- Sá, M., et al. Aortic valve neocuspidization with glutaraldehyde-treated autologous pericardium (Ozaki Procedure) - A promising surgical technique. Brazilian Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery. 34 (5), 610-614 (2019).

- Karamlou, T., Pettersson, G., Nigro, J. J. Commentary: A pediatric perspective on the Ozaki procedure. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 161 (5), 1582-1583 (2021).

- Mazine, A., et al. Ross procedure in adults for cardiologists and cardiac surgeons: JACC state-of-the-art review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 72 (22), 2761-2777 (2018).

- Kwak, J. G., et al. Long-term durability of bioprosthetic valves in pulmonary position: Pericardial versus porcine valves. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 160 (2), 476-484 (2020).

- Ou-Yang, W. B., et al. Multicenter comparison of percutaneous and surgical pulmonary valve replacement in large RVOT. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 110 (3), 980-987 (2020).

- Reimer, J., et al. Implantation of a tissue-engineered tubular heart valve in growing lambs. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 45 (2), 439-451 (2017).

- Schmitt, B., et al. Percutaneous pulmonary valve replacement using completely tissue-engineered off-the-shelf heart valves: six-month in vivo functionality and matrix remodelling in sheep. EuroIntervention. 12 (1), 62-70 (2016).

- Whiteside, W., et al. The utility of intracardiac echocardiography following melody transcatheter pulmonary valve implantation. Pediatric Cardiology. 36 (8), 1754-1760 (2015).

- Lancellotti, P., et al. Recommendations for the echocardiographic assessment of native valvular regurgitation: an executive summary from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. European Heart Journal. Cardiovascular Imaging. 14 (7), 611-644 (2013).

- Kuang, D., Lei, Y., Yang, L., Wang, Y. Preclinical study of a self-expanding pulmonary valve for the treatment of pulmonary valve disease. Regenerative Biomaterials. 7 (6), 609-618 (2020).

- Arboleda Salazar, R., et al. Anesthesia for percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation: A case series. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 127 (1), 39-45 (2018).

- Cho, S. K. S., et al. Feasibility of ventricular volumetry by cardiovascular MRI to assess cardiac function in the fetal sheep. The Journal of Physiology. 598 (13), 2557-2573 (2020).

- Sun, X., et al. Four-dimensional computed tomography-guided valve sizing for transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement. Journal of Visualized Experiments: JoVE. (179), e63367 (2022).

- Knirsch, W., et al. Establishing a pre-clinical growing animal model to test a tissue engineered valved pulmonary conduit. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 12 (3), 1070-1078 (2020).

- Zhang, X., et al. Tissue engineered transcatheter pulmonary valved stent implantation: current state and future prospect. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (2), 723 (2022).

- Al Hussein, H., et al. Challenges in perioperative animal care for orthotopic implantation of tissue-engineered pulmonary valves in the ovine model. Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. 17 (6), 847-862 (2020).

- Emmert, M. Y., et al. Computational modeling guides tissue-engineered heart valve design for long-term in vivo performance in a translational sheep model. Science Translational Medicine. 10 (440), (2018).

- Schmidt, D., et al. Minimally-invasive implantation of living tissue engineered heart valves: . a comprehensive approach from autologous vascular cells to stem cells. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 56 (6), 510-520 (2010).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionExplore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved