Method Article

Combining Mitotic Cell Synchronization and High Resolution Confocal Microscopy to Study the Role of Multifunctional Cell Cycle Proteins During Mitosis

In This Article

Summary

We present a protocol for double thymidine synchronization of HeLa cells followed by analysis using high resolution confocal microscopy. This method is key to obtaining large number of cells that proceed synchronously from S phase to mitosis, enabling studies on mitotic roles of multifunctional proteins which also possess interphase functions.

Abstract

Study of the various regulatory events of the cell cycle in a phase-dependent manner provides a clear understanding about cell growth and division. The synchronization of cell populations at specific stages of the cell cycle has been found to be very useful in such experimental endeavors. Synchronization of cells by treatment with chemicals that are relatively less toxic can be advantageous over the use of pharmacological inhibitory drugs for the study of consequent cell cycle events and to obtain specific enrichment of selected mitotic stages. Here, we describe the protocol for synchronizing human cells at different stages of the cell cycle, including both in S phase and M phase with a double thymidine block and release procedure for studying the functionality of mitotic proteins in chromosome alignment and segregation. This protocol has been extremely useful for studying the mitotic roles of multifunctional proteins which possess established interphase functions. In our case, the mitotic role of Cdt1, a protein critical for replication origin licensing in G1 phase, can be studied effectively only when G2/M-specific Cdt1 can be depleted. We describe the detailed protocol for depletion of G2/M-specific Cdt1 using double thymidine synchronization. We also explain the protocol of cell fixation, and live cell imaging using high resolution confocal microscopy after thymidine release. The method is also useful for analyzing the function of mitotic proteins under both physiological and perturbed conditions such as for Hec1, a component of the Ndc80 complex, as it enables one to obtain large sample sizes of mitotic cells for fixed and live cell analysis as we show here.

Introduction

In the cell cycle, cells undergo a series of highly regulated and temporally controlled events for the accurate duplication of their genome and proliferation. In mammals, the cell cycle consists of interphase and M-phase. In interphase, which consists of three stages- G1, S, and G2, the cell duplicates its genome and undergoes growth that is necessary for normal cell cycle progression1,2. In the M-phase, which consists of mitosis (prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase) and cytokinesis, a parental cell produces two genetically identical daughter cells. In mitosis, sister chromatids of duplicated genome are condensed (prophase) and are captured at their kinetochores by microtubules of the assembled mitotic spindle (prometaphase), that drives their alignment at the metaphase plate (metaphase) followed by their equal segregation when sister chromatids are split toward and transported to opposite spindle poles (anaphase). The two daughter cells are physically separated by the activity of an actin-based contractile ring (telophase and cytokinesis). The kinetochore is a specialized proteinaceous structure which assembles at the centromeric region of chromatids and serve as attachment sites for spindle microtubules. Its main function is to drive chromosome capture, alignment, and aid in correcting improper spindle microtubule attachment, while mediating the spindle assembly checkpoint to maintain the fidelity of chromosome segregation3,4.

The technique of cell synchronization serves as an ideal tool for understanding the molecular and structural events involved in cell cycle progression. This approach has been used to enrich cell populations at specific phases for various types of analyses, including profiling of gene expression, analyses of cellular biochemical processes, and detection of subcellular localization of proteins. Synchronized mammalian cells can be used not only for the study of individual gene products, but also for approaches involving analysis of whole genomes including microarray analysis of gene expression5, miRNA expression patterns6, translational regulation7, and proteomic analysis of protein modifications8. Synchronization can also be used to study the effects of gene expression or protein knock-down or knock-out, or of chemicals on cell cycle progression.

Cells can be synchronized at the different stages of the cell cycle. Both physical and chemical methods are widely used for cell synchronization. The most important criteria for cell synchronization are that synchronization should be noncytotoxic and reversible. Because of the potential adverse cellular consequences of synchronizing cells by pharmacological agents, chemical-dependent methods can be advantageous for studying key cell cycle events. For example, hydroxyurea, amphidicolin, mimosine, and lovastatin, can be used for cell synchronization at G1/S phase but, because of their effect on the biochemical pathways they inhibit, they activate cell cycle checkpoint mechanisms and kill an important fraction of the cells9,10. On the other hand, feedback inhibition of DNA replication by adding thymidine to the growth media, known as "thymidine block", can arrest the cell cycle at certain points11,12,13. Cells can also be synchronized at G2/M phase by treating with nocodazole and RO-33069,14.Nocodazole, which prevents microtubule assembly, has a relatively high cytotoxicity. Moreover, nocodazole-arrested cells can return to interphase precociously by mitotic slippage. Double thymidine block arrest cells at G1/S phase and after release from the block, cells are found to proceed synchronously through G2 and into mitosis. The normal progression of the cell cycle for cells released from thymidine block can be observed under high resolution confocal microscopy by either cell fixation or live imaging. The effect of perturbation of mitotic proteins can be studied specifically when cells enter and proceed through mitosis after release from double thymidine block. Cdt1, a multifunctional protein, is involved in DNA replication origin licensing in the G1 phase and is also required for kinetochore microtubule attachments during mitosis15. To study the function of Cdt1 during mitosis, one needs to adopt a method that avoids the effect of its depletion on replication licensing during G1 phase, while at the same time effecting its depletion specifically during the G2/M phase only. Here, we present detailed protocols based on the double thymidine block to study the mitotic role of proteins performing multiple functions during different stages of the cell cycle by both fixed and live-cell imaging.

Protocol

1. Double Thymidine Block and Release: Reagent Preparations

- Make 500 mL Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin, and streptomycin.

- Make 100 mM stock of thymidine in sterile water and store in aliquots at -80 °C.

2. Protocol for Fixed Cell Imaging of Mitotic Progression (Figure 1A)

- On day 1, seed ~2 x 105 HeLa cells into the wells of a 6-well plate with a cover slip (sterilized with 70% ethanol and UV irradiation) and 2 mL of DMEM medium. Grow the cells in a humidified incubator for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

- 1st thymidine block: On day 2, thoroughly mix the required volume of thymidine in fresh DMEM media (100 mM stock, 2 mM final concentration).

- Add 2 mL of thymidine-containing media to the cells in each well of the 6-well plate and incubate for 18 h.

- On day 3, aspirate the medium and wash the cells twice with 2 mL of 1x PBS and once with fresh prewarmed DMEM; grow cells in fresh prewarmed DMEM medium for 9 h to release cells from block.

- 2nd thymidine block: Again add 2 mL of thymidine-containing media (2 mM final concentration) to the cells in each well of the 6-well plate.

- Incubate for another 18 h.

- On day 4, aspirate the medium and wash the cells twice with 2 mL of 1x PBS and once with fresh prewarmed DMEM.

- Dilute siRNAs (control and Cdt1) and transfection reagent in serum free growth medium separately for 10 min. Mix them together and incubate for 20 min at RT. The final concentration of siRNA used in each transfection was 100 nM. Add the reaction mixture to the cells that have been washed out of Thymidine.

- Incubate cells at 37 °C for 9-10 h to release from blocking and fix the cells on the cover slips with 4% PFA for 20 min at RT.

Caution: PFA is toxic, wear appropriate protection. - Immunostain cells, after permeabilizing with 0.5% (v/v) detergent for 10 min at RT and washing the cells twice with 1x PBS for 5 min each.

- Block cells with 1% BSA (w/v) in 1x PBS for 1 h at RT followed by treating cells with 50 µL of primary antibodies (mouse anti-α-tubulin antibody diluted at 1:1,000, rabbit anti-Zwint1 antibody diluted at 1:400, and mouse anti-phospho-ɣ H2AX diluted at 1:300) in 1% (w/v) BSA in 1x PBS for 1 h at 37 oC.

- After washing out the cells with 1x PBS thrice, treat cells with 50 µL of secondary antibodies for each cover glass (Alexa 488 and Rhodamine Red at 1:250 dilutions in 1% (w/v) BSA in 1x PBS) for 1 h at RT.

- After washing the cells with 1x PBS twice for 5 min each, treat cells with DAPI (0.1µg/mL in 1x PBS) for 5 min at RT.

- After washing the cells with 1x PBS twice for 5 min each, place the cover slip facing cells to the appropriate mounting media on a clear microscopic slide.

- Image the cells for the immunostained proteins with 60X or 100X 1.4 NA Plan-Apochromatic DIC oil immersion objective mounted on an inverted high resolution confocal microscope equipped with an appropriate camera as necessary for the quality of images required.

- Acquire images at room temperature as z-stacks of 0.2 µm thickness using software appropriate for the microscope.

3. Protocol for Live Cell Imaging of Mitotic Progression (Figure 3A)

- On day 1, seed approximately 0.5-1 x 105 HeLa cells stably expressing mCherry-H2B and GFP-α-tubulin (slightly variable based on cell type and the proteins they express) into 35 mm glass bottom dishes with 1.5 mL of DMEM medium and grow them in a humidified incubator for 24 h at 37 oC and 5% CO2.

- 1st thymidine block: On day 2, add 1.5 mL of thymidine-containing media to the cells in the dish (100 mM thymidine, 2 mM final concentration,).

- Incubate for 18 h.

- On day 3, aspirate the medium containing thymidine and wash the cells thrice, twice with 2 mL of 1x PBS and once with fresh prewarmed DMEM.

- Dilute siRNAs (control and Hec1) and transfection reagent with serum free growth medium separately for 10 min. Mix them together and incubate for 20 min at RT. The final concentration of siRNA used in each transfection was 100 nM. Add the reaction mixture to the cells that have been washed out of Thymidine.

- Grow cells in 1.5 mL of fresh prewarmed DMEM medium for 8 h to release cells from block.

- 2nd thymidine block: Add 1.5 mL of thymidine-containing media (2 mM final concentration) to the cells in the dish.

- Incubate for another 18 h.

- On day 4, aspirate the medium and wash the cells thrice, twice with 2 mL of 1x PBS and once with fresh prewarmed DMEM. Then grow cells in fresh prewarmed Leibovitz's (L-15) medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 20 mM HEPES at pH 7.0 for 8 h to release cells from the block.

- Place the dish in the temperature control chamber set in the high resolution confocal microscope which has already switched on at least 30 min before beginning the imaging to stabilize the on-stage and experimental temperatures.

- Focus in bright field with 60x objective until cells are visible, then manually sift the on-stage to the region of choice.

- Set up the light and laser power/exposure, image acquisition parameters, and duration of the experiment using the microscope image acquisition software of choice. Use filters for GFP (488 excitation; 385 nm emission) and mCherry (561 nm excitation and 385 nm emission) to acquire images.

- Perform the time-lapse experiment by separately acquiring pulsed transmitted light and fluorescence images every 10 min for a period up to 16 h.

- Acquire images as twelve 1.0 µm-separated z-planes at 9 h after release from the double thymidine block using software appropriate to the microscope.

- Analyze the images tracking individual cells for mitotic progression and finally assemble the corresponding movie with the source software Fiji/ImageJ.

Results

Study of mitotic progression and microtubule stability in cells fixed after release from double thymidine block

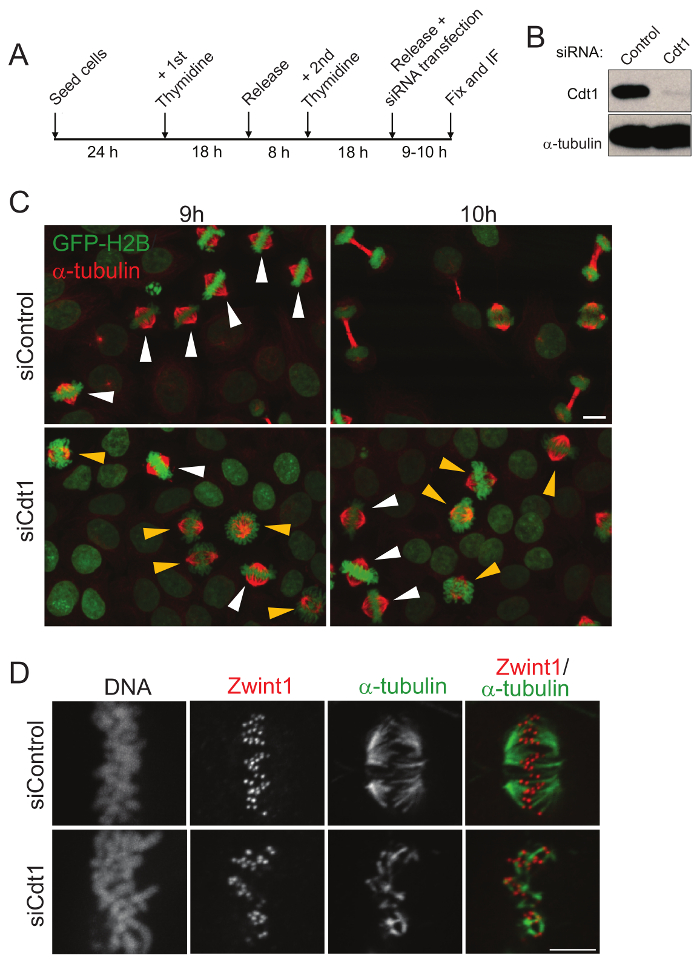

Cdt1 is involved in licensing of DNA replication origins in the G1 phase. It is degraded during S phase but re-accumulates in G2/M phase. To study its role in mitosis, the endogenous Cdt1 needs to be depleted specifically at the G/M phase using the most suitable cell synchronization technique, the double thymidine block15. Cells were transfected with siRNAs immediately after release from the 2nd thymidine block, when cells are in the S phase and by which time the licensing of replication origins in G1, which also requires Cdt1 function, has long been completed. The depletion of Cdt1 after 9 h of siCdt1 transfection and double thymidine block release was validated by Western blotting (Figure 1B). Fixation of cells 9 h after release from the double thymidine block shows that most cells are at the metaphase stage in both control and Cdt1 siRNA transfected cells. But fixation of cells 10 h after release from the double thymidine block shows that most Cdt1 siRNA-treated cells are still arrested in late prometaphase stage while control cells enter anaphase and normally segregate their chromosomes as expected (Figure 1C). To understand the effect of Cdt1 depletion on kinetochore-microtubule (kMT) stability, cells were fixed at 9 h after release from double thymidine block followed by cold treatment, which only retains stable kinetochore-microtubules (kMTs). The kMTs of Cdt1-depleted cells are relatively less robust after cold treatment compared to that of control cells (Figure 1D). Thus, using this approach, the progression of normal mitotic cells after the perturbation of the function of mitotic protein(s) of interest can be studied effectively, even without the use of live cell imaging.

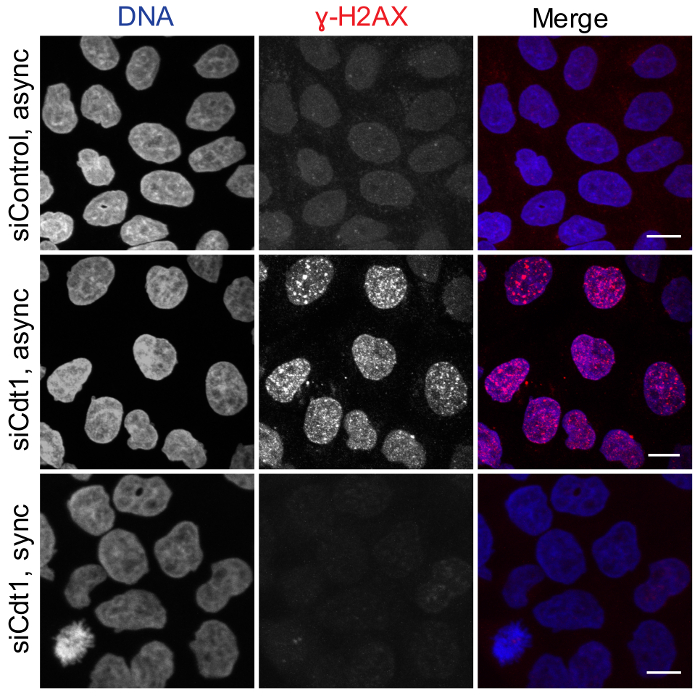

Figure 2 shows that licensing of DNA replication origin is not perturbed when cells are depleted of Cdt1 during G2/M phase using our protocol, which was also observed in control cells. Cells depleted of Cdt1 during G2/M phase did not induce accumulation of phosphorylated ɣH2AX, a marker for DNA damage, during the subsequent G2 phase; whereas siRNA transfection of asynchronous cultures to deplete Cdt1 induced accumulation of phospho-ɣH2AX-positive foci, possibly due to DNA damage induced by improper DNA replication licensing.

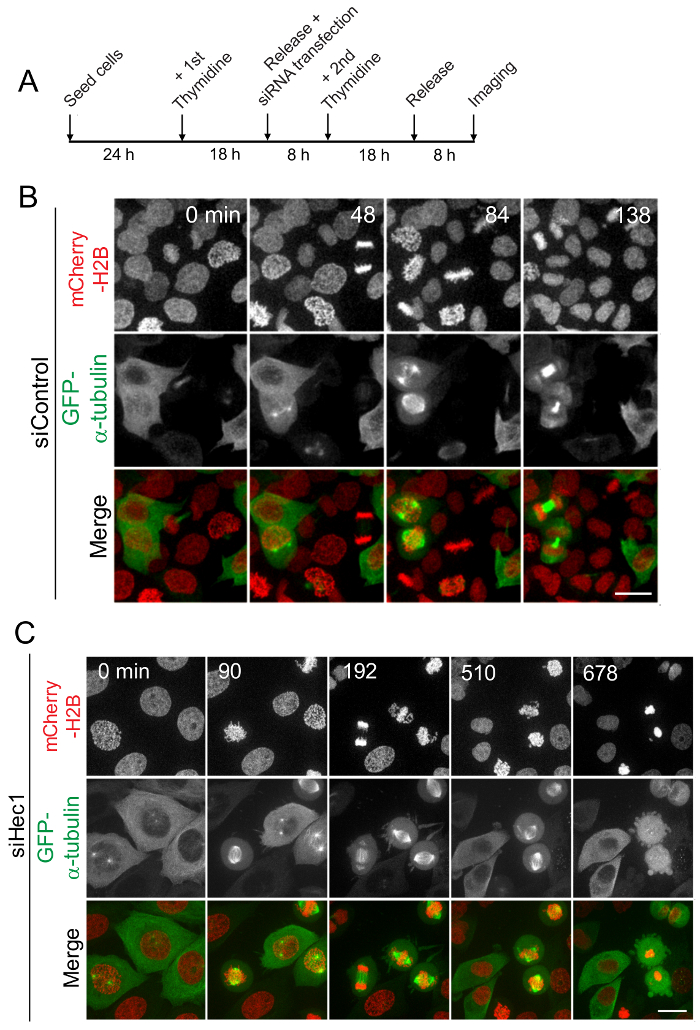

Study of mitotic progression in cells after release from double thymidine block by live cell imaging

After the nuclear envelope breakdown (NEB), normal cells (in the absence of perturbation by a functional mitotic protein) enter mitosis and undergo anaphase onset to exit from mitosis within about 30-60 min (Figure 3B). But RNAi-mediated knockdown of Hec1, a key kinetochore protein that is required for robust kMT attachment formation, is found to delay normal mitotic progression. In this scenario, most cells enter mitosis after the NEB, but do not undergo anaphase onset or exit from mitosis even after several hours of delay in mitosis (Figure 3C). Similarly, the effect of RNAi-mediated knockdown of any other protein that localizes to kinetochores or having a function during mitosis can thus be observed effectively by using live cell imaging after release from double thymidine blocks. In addition to studying the nature of mitotic progression, delay, and arrest, some of the other key mitotic phenomena that can be assayed using this method include chromosome alignment, mitotic spindle formation, and positioning the activation and silencing of the spindle assembly checkpoint.

Figure 1: Analysis of mitotic progression and the stability of kinetochore microtubules in fixed cells after double thymidine synchronization. (A) A schematic representation of cell synchronization, fixation, and immunofluorescence. (B) Western blot for knockdown of Cdt1 after 9 h of release from 2nd thymidine block. (C) Immunofluorescence micrographs to show the mitotic cells fixed 9 and 10 h after release from double thymidine block and treatment with control (top) or Cdt1 siRNA (bottom). α-tubulin staining is in red, DNA is in green as cells express GFP-Histone H2B. Scale bar = 10 µm. Prometaphase and metaphase cells are indicated using yellow and white arrowheads respectively. (D) HeLa cells after treatment with control siRNA (top panel) and after Cdt1 depletion (bottom panel) for 9 h after release from double thymidine block followed by treatment with ice-cold Leibovitz's (L-15) medium and fixation. Cells were immune-stained for spindle MT (green) and a kinetochore marker, Zwint1 (red) and DAPI for DNA in black and white. Scale bar = 5 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Cdt1-depletion during G2/M phase does not perturb replication licensing. Asynchronous HeLa cells treated with control luciferase (top panel) or cdt1 siRNAs (middle panel) or double thymidine synchronized HeLa cells treated with cdt1 siRNA during the 2nd thymidine wash-out followed by fixation at 10 h after release (bottom panel) were stained with DAPI (pseudo-colored green) and anti-phospho-ɣH2AX antibody (red). Scale Bar = 10 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Analysis of mitotic progression by live cell imaging in synchronized cells. (A) A schematic representation of cell synchronization and live cell imaging. HeLa cells stably expressing mCherry-Histone H2B and GFP-α-tubulin were released from double thymidine block for 8 h to let them proceed to G2/M phase from S phase arrest. Live imaging was carried out using a high resolution confocal microscope starting 8 h after releasing the cells from thymidine block and continuing for up to 16 h from that point. Shown here are the still images from the video captured every 10 min for control cells without perturbation of any mitotic protein (B) or for cells depleted of the Hec1 subunit of the Ndc80 complex (C). Scale Bars = 10 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

The most critical advantage of double thymidine synchronization is that it provides an increased sample size of mitotic cells in a short time window with many of these cells entering mitosis in unison, thus also enabling analyses of chromosome alignment, bipolar spindle formation, and chromosome segregation with much higher efficiency.

Many regulatory protein complexes and signaling pathways are devoted to ensuring normal progression through mitosis and deregulation of this process may led to tumorigenesis. Live cell imaging of HeLa cells stably expressing mCherry-H2B and GFP-tubulin and released from the double thymidine block shows that most control cells segregate their chromosomes at anaphase within approximately 60 min after NEB (Figure 3B). On the other hand, live cell imaging of HeLa cells perturbed with Hec1 function shows that most cells stay in the mitotic phase for a long period with misaligned chromosomes followed by anaphase onset or apoptosis (Figure 3C).

Excess thymidine inhibits DNA synthesis during the S phase, thus blocking cells at G1/S phase11. Although double thymidine block synchronization is the most commonly used method in the study of the cell cycle and mitotic progression, one needs to be critical of some of the limitations of this method. Importantly, it needs to be ensured that the chemical has been washed out thoroughly (for 7-8 h) so that the effect is completely reversible and cells can proceed normally through the rest of the cell cycle. Cells may otherwise not enter the second cycle causing improper progression though mitosis. The proportion of synchronized cells may not be sufficiently high with a single thymidine block and a double thymidine block may be necessary to increase the number of synchronized cells, especially if one is interested in studying a specific stage of mitosis. The duration of the thymidine treatment must be optimized due to different sensitivity among cell types depending on the generation time. For example, hamster cells have 16 h of generation time and are treated with thymidine for 11 h for optimal synchronization17. In this study, we treated HeLa cells for 16-18 h with thymidine. Moreover, the excess thymidine not only prevents DNA synthesis but also may kill important fractions of the cells11,12,18 and close attention needs to be paid to monitor this loss. The thymidine stock solution used in this study should be prepared in sterile distilled water and should be mixed thoroughly in the cell culture media to avoid its precipitation after adding it to media of siRNA transfected cells and also to ensure its homogenous distribution around the cultured cells.

For studying the function of a target mitotic protein during mitotic progression, the cells would ideally be treated with siRNA to knockdown the levels of the protein of interest either during the 1st thymidine block or during the release from the 1st thymidine block, depending upon the time required to obtain efficient protein knockdown19,20,21. On the other hand, for studying the role of multifunctional proteins such as Cdt1 during mitosis, it is necessary to treat the cells with siCdt1 during the release from the 2nd thymidine block to obtain G2/M specific depletion. Cdt1 is a critical player in the licensing of DNA replication origins15. To understand its specialized role during mitosis without interfering with its role in licensing, Cdt1 needs to be depleted specifically at G2/M phase, which can be efficiently achieved by double thymidine synchronization, thus avoiding the need to resort to other mitosis-specific perturbation approaches that are difficult to execute. Depletion of Cdt1 in asynchronous cultures induce DNA damage response due to the interruption of the licensing of DNA replication origins, which would in turn have muddled the analysis of a possible function for this protein during mitosis. Thus, the double thymidine synchronization technique offers a unique experimental approach to generate cells that underwent a normal G1 and S phase but lacked Cdt1 function during G2 and M phase. The special significance of our synchronization protocol lies in its inhibition of multifunctional proteins at the specific phase (G2/M) to study their novel functions during mitosis. Thus, this method will be useful not only to study the role of proteins that have multiple functions during different cell cycle stages but also of that of any mitotic protein in the process of chromosome alignment, kMT attachments, and chromosome segregation.

For live cell imaging, after release from the double thymidine block, cells should be incubated in pre-warmed Leibovitz's (L-15) medium supplemented with 10-20% FBS until the beginning of imaging. The cells enter mitosis at variable time points after release from thymidine block depending on the cell type. The start time of image capturing or fixation needs to be optimized depending on the cell type. For live cell imaging, the utilization of conventional confocal microscopy may cause photobleaching during long-term imaging. On the other hand, the high resolution confocal microcopy gives a clear and high-resolution image with the least extent of photobleaching effects.

The critical steps in this protocol are the duration of thymidine treatment, proper washout of the thymidine, the timing of siRNA transfection, and the start timing of imaging.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interest.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Kozo Tanaka of Tohoku University, Japan for sharing HeLa cells stably expressing mCherry-Histone H2B and GFP-α-tubulin. This work was supported by an NCI grant to DV (R00CA178188) and by start-up funds from Northwestern University.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| DMEM (1x) | Life Technologies | 11965-092 | Store at 4 °C |

| DPBS (1x) | Life Technologies | 14190-144 | Store at 4 °C |

| Leibovitz’s (1x) L-15 medium | Life Technologies | 21083-027 | Store at 4 °C |

| Serum reduced medium (Opti-MEM) | Life Technologies | 319-85-070 | Store at 4 °C |

| Penicillin and streptomycin | Life Technologies | 15070-063 (Pen Strep) | 1:1,000 dilution |

| Dharmafect2 | GE Dharmacon | T-2002-02 | Store at 4 °C |

| Thymidine | MP Biomedicals LLC | 103056 | Dissolved in sterile distiled water |

| Cdt1 siRNA | Life Technologies | Ref 10 | |

| Hec1 siRNA | Life Technologies | Ref 13 | |

| HeLa cells expressing GFP-H2B | |||

| HeLa cells expressing GFP-α-tubulin and mCherry H2B | Generous gift from Dr. Kozo Tanaka of Tohoku university, Japan | ||

| Formaldehyde solution | Sigma-Aldrich Corporation | F8775 | Toxic, needs caution |

| DAPI | Sigma-Aldrich Corporation | D9542 | Toxic, needs caution |

| Mouse anti-α-tubulin | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Sc32293 | 1:1,000 dilution |

| Rabbit ant-Zwint1 | Bethyl | A300-781A | 1:400 dilution |

| Mouse anti-phospho-γH2AX (Ser139) | Upstate Biotechnology | 05-626, clone JBW301 | 1:300 dilution |

| Alexa 488 | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 1:250 dilution | |

| Rodamine Red-X | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 1:250 dilution | |

| BioLite 6 well multidish | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 130184 | |

| 35 mm Glass bottom dish | MatTek Corporation | P35GCOL-1.5-14-C | |

| Nikon Eclipse TiE inverted microscope | Nikon Instruments | ||

| Spinning disc for confocal | Yokagawa | CSU-X1 | |

| Ultra 888 EM-CCD Camera | Andor | iXon Ultra EMCCD | |

| 4 wave length laser | Agilent Technologies | ||

| Incubation System for Microscopes | Tokai Hit | TIZB | |

| NIS-elements software | Nikon Instruments |

References

- Lajtha, L. G., Oliver, R., Berry, R., Noyes, W. D. Mechanism of radiation effect on the process of synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid. Nature. 182 (4652), 1788-1790 (1958).

- Puck, T. T., Steffen, J. Life Cycle Analysis of Mammalian Cells. I. A Method for Localizing Metabolic Events within the Life Cycle, and Its Application to the Action of Colcemide and Sublethal Doses of X-Irradiation. Biophys. J. 3, 379-392 (1963).

- Santaguida, S., Musacchio, A. The life and miracles of kinetochores. EMBO J. 28 (17), 2511-2531 (2009).

- Musacchio, A., Desai, A. A Molecular View of Kinetochore Assembly and Function. Biology (Basel). 6 (1), E5 (2017).

- Chaudhry, M. A., Chodosh, L. A., McKenna, W. G., Muschel, R. J. Gene expression profiling of HeLa cells in G1 or G2 phases. Oncogene. 21 (12), 1934-1942 (2002).

- Zhou, J. Y., Ma, W. L., Liang, S., Zeng, Y., Shi, R., Yu, H. L., Xiao, W. W., Zheng, W. L. Analysis of microRNA expression profiles during the cell cycle in synchronized HeLa cells. BMB Rep. 42 (9), 593-598 (2009).

- Stumpf, C. R., Moreno, M. V., Olshen, A. B., Taylor, B. S., Ruggero, D. The translational landscape of the mammalian cell cycle. Mol. Cell. 52 (4), 574-582 (2013).

- Chen, X., Simon, E. S., Xiang, Y., Kachman, M., Andrews, P. C., Wang, Y. Quantitative proteomics analysis of cell cycle-regulated Golgi disassembly and reassembly. J. Biol. Chem. 285 (10), 7197-7207 (2010).

- Rosner, M., Schipany, K., Hengstschläger, M. Merging high-quality biochemical fractionation with a refined flow cytometry approach to monitor nucleocytoplasmic protein expression throughout the unperturbed mammalian cell cycle. Nature Protocols. 8 (3), 602-626 (2013).

- Coquelle, A., et al. Enrichment of non-synchronized cells in the G1, S and G2 phases of the cell cycle for the study of apoptosis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 72 (11), 1396-1404 (2006).

- Amon, A. Synchronization procedures. Methods Enzymol. 351, 457-467 (2002).

- Cooper, S. Rethinking synchronization of mammalian cells for cell cycle analysis. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 60 (6), 1099-1106 (2003).

- Whitfield, M. L., Sherlock, G., Saldanha, A. J., Murray, J. I., Ball, C. A., Alexander, K. E., Matese, J. C., Perou, C. M., Hurt, M. M., Brown, P. O., Botstein, D. Identification of genes periodically expressed in the human cell cycle and their expression in tumors. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13 (6), 1977-2000 (2002).

- Vassilev, L. T., et al. Selective small-molecule inhibitor reveals critical mitotic functions of human CDK1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 103 (28), 10660-10665 (2006).

- Varma, D., Chandrasekaran, S., Sundin, L. J., Reidy, K. T., Wan, X., Chasse, D. A., Nevis, K. R., DeLuca, J. G., Salmon, E. D., Cook, J. G. Recruitment of the human Cdt1 replication licensing protein by the loop domain of Hec1 is required for stable kinetochore-microtubule attachment. Nat. Cell Biol. 14 (6), 593-603 (2012).

- Garcia, M., Westley, B., Rochefort, H. 5-Bromodeoxyuridine specifically inhibits the synthesis of estrogen-induced proteins in MCF7 cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 116 (2), 297-301 (1981).

- Bostock, C. J., Prescott, D. M., Kirkpatrick, J. B. An evaluation of the double thymidine block for synchronizing mammalian cells at the G1-S border. Exp. Cell Res. 68 (1), 163-168 (1971).

- Martin-Lluesma, S., Stucke, V. M., Nigg, E. A. Role of Hec1 in spindle checkpoint signaling and kinetochore recruitment of Mad1/Mad2. Science. 297, 2267-2270 (2002).

- Brouwers, N., Mallol Martinez, N., Vernos, I. Role of Kif15 and its novel mitotic partner KBP in K-fiber dynamics and chromosome alignment. PLoS One. 12 (4), e0174819 (2017).

- Dou, Z., et al. Dynamic localization of Mps1 kinase to kinetochores is essential for accurate spindle microtubule attachment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 112 (33), E4546-E4555 (2015).

- Chan, Y. W., Jeyaprakash, A. A., Nigg, E. A., Santamaria, A. Aurora B controls kinetochore-microtubule attachments by inhibiting Ska complex-KMN network interaction. J Cell Biol. 196 (5), 563-571 (2012).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved