Method Article

A Protocol for Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass in Rats using Linear Staplers

W tym Artykule

Podsumowanie

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is performed to treat obesity and diabetes. However, the mechanisms underlying RYGB's efficacy are not fully understood, and studies are limited by technical difficulty leading to high mortality in animal models. This article provides instructions on how to perform RYGB in rats with high success rates.

Streszczenie

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is commonly performed for the treatment of severe obesity and type 2 diabetes. However, the mechanism of weight loss and metabolic changes are not well understood. Multiple factors are thought to play a role, including reduced caloric intake, decreased nutrient absorption, increased satiety, the release of satiety-promoting hormones, shifts in bile acid metabolism, and alterations in the gut microbiota.

The rat RYGB model presents an ideal framework to study these mechanisms. Prior work on mouse models have had high mortality rates, ranging from 17 to 52%, limiting their adoption. Rat models demonstrate more physiologic reserve to surgical stimulus and are technically easier to adopt as they allow for the use of surgical staplers. One challenge with surgical staplers, however, is that they often leave a large gastric pouch which is not representative of RYGB in humans.

In this protocol, we present a RYGB protocol in rats that result in a small gastric pouch using surgical staplers. Utilizing two stapler fires which remove the forestomach of the rat, we obtain a smaller gastric pouch similar to that following a typical human RYGB. Surgical stapling also results in better hemostasis than sharp division. Additionally, the forestomach of the rat does not contain any glands and its removal should not alter the physiology of RYGB.

Weight loss and metabolic changes in the RYGB cohort were significant compared to the sham cohort, with significantly lower glucose tolerance at 14 weeks. Furthermore, this protocol has an excellent survival of 88.9% after RYGB. The skills described in this protocol can be acquired without previous microsurgical experience. Once mastered, this procedure will provide a reproducible tool for studying the mechanisms and effects of RYGB.

Wprowadzenie

Obesity and type 2 diabetes have become worldwide epidemics1. Although medical weight loss can improve diabetes in patients, those with severe diabetes benefit most from bariatric surgery. Bariatric surgery has proven to be safe and effective at weight loss and improving or curing type 2 diabetes2,3, even in those with long-standing disease4. Metabolic bariatric procedures, such as the current gold-standard Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery, induce rapid and sustained improvements in glucose homeostasis while also reducing the need for diabetic medications5,6,7.

After RYGB, glucose homeostasis improvement occurs rapidly and is independent of the weight loss8. Two major theories have been proposed to explain the metabolic changes associated with diabetes remission that occur following metabolic surgery. First, the hindgut hypothesis postulates that, after bypass, higher concentrations of undigested nutrients reach the distal intestine enhancing the release of hormones such as GLP-1. On the other hand, the foregut hypothesis suggests that bypassing the proximal intestine reduces the secretion of anti-incretin hormones. Both of these effects could lead to early improvement of glucose metabolism9.

Animal models have the potential to be a powerful tool to study these mechanisms. However, a major barrier in utilizing mouse or rat models is the technical difficulty in performing these procedures. Most studies have relied on mouse or rat models10,11,12. Mouse models have been difficult as the mouse stomach is too small to use stapler devices11, and mortality rates are unacceptably high, ranging from 17 to 52%13. In rats, some protocols remain technically difficult to perform due to complex ligation of gastric vessels prior to dividing the stomach12,14. Other models divide the stomach using a stapler but leave a large pouch not consistent with the post RYGB human anatomy11. In this model, we provide detailed instructions on how to perform RYGB using linear staplers in a rat model resulting in a gastric pouch more in keeping with that of human anatomy. Overall, this procedure was associated with excellent survival rates and metabolic outcomes.

Protokół

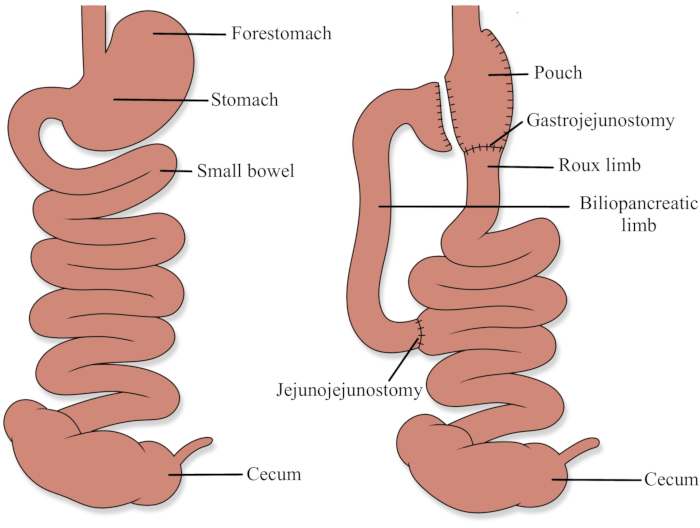

Animal use protocols were approved by the Health Science Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Alberta (AUP00003000). See Figure 1 for a diagram demonstrating the RYGB anatomy.

1. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

- Preparation of animals and operative setup

- One week prior to the surgery, provide the rats with oral rehydration therapy and liquid diet in addition to their solid diet and water to acclimatize them to this new diet.

- Fast rats with only access to water for 12-18 h prior to the surgery.

- Ensure rats are fasted on a raised wire platform so that they cannot consume bedding material.

- Inject rats with subcutaneous long buprenorphine sustained release (SR) at a dose of 1 mg/kg immediately before surgery.

- Autoclave all surgical instruments, towels, and drapes.

- Clean the operating surface, heating pad, and anesthetic nose cone with 70% ethanol.

- Set up the operating surface with an operating microscope, anesthetic machine, and supplies in a manner that is ergonomic for the operating surgeon.

- Use a temperature-regulated heating pad and set to 37 °C.

- Place a sterile drape or towel over the heating pad.

- Fill a 50 mL sterile conical tube with 0.9% saline.

- Anesthetic induction and preparation

- Induce anesthesia using 4% isoflurane as per previously established protocols15.

- Apply pressure to the hindfoot of all four limbs to ensure there is no pain response.

- Check for adequate anesthesia and respiratory rate after every 5 min.

- Apply lubricant to both eyes to prevent drying.

- Shave hair from the abdomen.

- Clean the abdomen with a povidone-iodine solution. Allow the solution to dry, and change into sterile gloves.

- Drape the rat with an opening in the drape to expose the abdomen.

- Place instruments, sutures, cotton swabs, and a 10 mL syringe in a location that permits easy access during the procedure.

- Median laparotomy

- Make a 3 cm incision in the upper midline of the abdomen using a scalpel, just below the xyphoid process as a landmark.

- Using scissors, divide the fascia and peritoneum, with care to stay midline on the linea alba to reduce bleeding from the rectus abdominus. If there is bleeding, control it with thermal or electrocautery.

- Mobilizing the stomach

- Using two wet cotton swabs, bluntly dissect gastric attachments.

- When encountering dense adhesions, use thermal cautery to divide gastric attachments with care to avoid cauterizing the stomach. Sharply divide the ligament between the stomach and the accessory liver lobe to reduce the risk of liver tearing with stomach mobilization.

- For larger blood vessels, especially at the short gastric arteries, ligate using 6-0 polypropylene suture.

- Create a window on the right distal side of the esophagus but proximal to the left gastric artery. Ensure that a cotton swab can reach into this area posteriorly. The stomach is adequately mobilized when it can be exteriorized outside of the abdomen.

- Identify and divide the jejunum

- Identify the ligament of Treitz by following the jejunum proximally until observing it is attachment to the transverse mesocolon.

- Measure 7 cm distally, identify a location between mesenteric vessels, and divide the bowel with micro scissors. Avoid Peyer's patches when dividing the bowel. Take care to only divide the bowel and not the mesentery.

- Place a clean, saline soaked sponge prior to dividing the bowel to minimize contamination.

- Check for the presence of a small crossing vessel in the mesentery at the border of the small bowel and divide this with cautery to avoid bleeding.

- Continue to divide the mesentery 1 cm towards the mesenteric base.

- Identify the proximal and distal jejunum. Place the proximal jejunum under a wet gauze on the rat's right and the distal jejunum on the rat's left.

- Stapling the stomach

- Insert a 45 mm linear cutting stapler with 3.5 mm staple height across the white line of the forestomach to create a smaller pouch. Wait for 10 s before firing the stapler.

- Place pressure using gauze on the staple lines for 1 min to ensure hemostasis. If hemostasis is not achieved with pressure alone, bleeding along the staple line is oversewn using 6-0 polypropylene figure of eight sutures.

- Perform a second staple fire across the stomach into the window created previously. Wait for 10 s before firing the stapler. Pressure is held along the staple line to ensure hemostasis, and oversewing may be needed.

- Gastrojejunostomy

- Make a gastrotomy immediately after stapling the stomach. Delays in this can cause gastric distension and aspiration as the stomach is discontinuous after the second gastric staple.

- Using an 11-blade scalpel, create a gastrotomy at the distal pouch. Express gastric contents through the gastrotomy. This is important to prevent gastric distension and aspiration. Lengthen this gastrotomy using micro scissors to approximately 5 mm. The gastrotomy is made large enough for the cotton swab tip just to fit through.

- Mobilize the distal end of the jejunum adjacent to the gastrotomy and place such that the mesentery is not twisted.

- While suturing the anastomosis, ensure that the bowel is kept moist by covering it with saline-soaked gauze and reapplying saline regularly.

- Using 6-0 polydioxanone or polypropylene suture, place a stay suture at the inferior margin of the anastomosis and gently retract using a snap. Tie with three knots.

- Place a stay suture at the superior margin of the anastomosis and gently retract using a snap. Tie with six knots.

- Suture the anterior side of the anastomosis in a continuous fashion, taking bites 1 mm wide and 1 mm apart with care to avoid taking the backside.

- Once the suture has reached the inferior stay suture, tie these together with an additional six knots.

- Once the anterior side is complete, flip the bowel and stomach over and pass the inferior stay suture through the mesenteric defect. Reapply the snap and retract inferiorly.

- For the posterior side of the anastomosis, place full thickness interrupted 6-0 sutures, 1 mm wide, and spaced 1 mm apart, with care to avoid taking the backside. These are tied with six knots each.

NOTE: The anterior side of the anastomosis is sutured in a continuous fashion while the posterior side is done in an interrupted fashion. This prevents potential stricture or stenosis associated with a continuous circumferential closure. - Check for the leakage by gently pushing luminal contents across the anastomosis. If there are areas with leakage, carefully reinforce them with interrupted sutures. Take care to avoid taking the backwall when reinforcing with extra sutures.

- Jejunojejunostomy

- From the gastrojejunostomy, measure 20 cm distally.

- Create a jejunotomy on the antimesenteric side using the 11-blade scalpel. Avoid making the jejunotomy over Peyer's patches.

- Extend this jejunotomy using micro scissors, such that it is the same size as the biliopancreatic limb. Ensure that a cotton swab just fits inside.

- Place the biliopancreatic limb such that there is no twisting of the mesentery.

- Perform the anastomosis similarly to the gastrojejunostomy with 6-0 stay sutures on the superior and inferior sides. The anterior side is performed with continuous sutures while the posterior side is performed with interrupted sutures.

- Ensure that the bowel is kept moist with saline during this anastomosis.

- Check for leakage by gently pushing luminal contents through the anastomosis. If there are areas with leakage, reinforce them with interrupted sutures.

- Reposition the bowel and stomach

- Ensure that there is no twisting of the pouch, remnant stomach, or liver. Ensure that the left lobe of the liver is anterior to the stomach and not trapped behind the pouch as this can cause compressive liver ischemia.

- Position the bowel in the abdomen in its natural position such that there is no twisting.

- Abdominal closure

- Close the fascia with 3-0 polyglactin in a continuous fashion. 3-0 polydioxanone may also be used.

- Close the skin with 2-0 silk in a continuous fashion.

- Anesthetic emergence

- Decrease isoflurane to zero but continue supplemental oxygen.

- Administer a local anesthetic as a splash block to the incision.

- Administer 10 mL of subcutaneous 5% dextrose in normal saline (D5NS) in the subcutaneous tissue behind the neck.

- Place an Elizabethan rat collar before the rat is fully awake. Take care to fit it snugly but not too tight to cause discomfort.

NOTE: The collar is kept on until day 5 to prevent wound dehiscence.

2. Sham surgery

NOTE: Sham surgery is performed similar to RYGB, however, no anastomoses are performed.

- A gastrotomy is created and then closed with 6-0 polydioxanone or polypropylene sutures.

- A jejunotomy is created 7 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz and then closed with 6-0 polydioxanone or polypropylene sutures.

3. Postoperative care

- Postoperative care

- House rats individually and keep them on raised wire platforms until solid food is reintroduced to prevent consumption of bedding and luminal obstruction.

NOTE: Postoperative diet is resumed gradually as edema at the gastrojejunostomy can cause obstruction with the early resumption of solid diet. - Inspect the feet daily while rats are on raised wire platforms for any skin changes.

- Keep rats on water and oral rehydration therapy diet for the first 72 h.

- Administer 10 mL of D5NS every 12 h for the first 72 h.

- Administer subcutaneous short-acting buprenorphine at 0.01 mg/kg if rats appear to be in pain. The Rat Grimace Scale is used to assess for pain16.

- On postoperative day 3, add rodent liquid diet. Continue to provide water and oral rehydration therapy.

- On postoperative day 5, restart high-fat diet. Continue to provide water and liquid diet. Remove the Elizabethan collar.

- On postoperative day 7, discontinue liquid diet.

- Remove skin sutures on postoperative day 10-14.

- House rats individually and keep them on raised wire platforms until solid food is reintroduced to prevent consumption of bedding and luminal obstruction.

Wyniki

Animals and housing

36 male Wistar rats were housed in pairs and were fed 60% sterile rodent high-fat diet starting from six weeks of age (Figure 2). At 16 weeks of age, they underwent RYGB or sham surgery. After the first postoperative week, rats were resumed on a high fat diet. Half of the rats were euthanized at 2 weeks post-operative and the other half were euthanized at 14 weeks postoperative.

Mortality

Overall, 33 (91.7%) rats survived to the planned study endpoint. All rats undergoing early euthanasia underwent necropsy by a veterinarian. Two rats were euthanized within 24 hours. One RYGB had aspiration pneumonitis and one sham rat had fascial dehiscence with unsalvageable bowel. Another RYGB rat was euthanized at two weeks due to anastomotic leak from the gastrojejunostomy. Overall, 88.9% of RYGB rats survived to study endpoint.

Body Weight

Rats undergoing RYGB had a lower postoperative weight than sham rats. Figure 3 demonstrates absolute weights for rats postoperatively while Figure 4 demonstrates postoperative percentage weight change which was statistically significant at all timepoints postoperatively. At 14 weeks, rats who had RYGB had a mean percentage weight change of 6.4% while rats with sham surgery had 23.7% (p = 0.0001).

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance testing

Fasting blood glucose was not significantly different between any of the cohorts. However, the area under the curve was significantly lower in RYGB compared with sham at 13 weeks (18.1 vs 23.8 mmol-h/L, p=0.046, Figure 5) but was the same for RYGB vs sham at 1 week (20.8 vs 23.3 mmol-h/L, p=0.68).

Figure 1: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass anatomy Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Preoperative absolute weight on high fat diet; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Postoperative absolute weight on high-fat diet; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: Postoperative percentage weight change on high-fat diet; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5: Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance testing in gastric bypass vs sham at 13 weeks. RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Dyskusje

RYGB involves the creation of a small gastric pouch (less than 30 mL), and the creation of a biliopancreatic limb and a Roux limb (Figure 1). In humans, the biliopancreatic limb is typically 30 to 50 cm and transports secretions from the gastric remnant, liver, and pancreas. The Roux limb is typically 75 to 150 cm in length and is the primary channel for ingested food. The common channel is the remaining small bowel distal to where the two limbs join and is where the majority of digestion and absorption occur, as pancreatic enzymes and bile mix with ingested food17.

The mechanism of weight loss in RYGB is multimodal. The small gastric pouch reduces food intake through mechanical restriction. The bypass results in a malabsorptive component as a significant portion of the small intestine is not absorbing calories and nutrients. More recently, studies have demonstrated that gut hormones play a significant role in weight loss after RYGB as well. These are primarily through ghrelin, peptide-YY, cholecystokinin (CCK), and GLP-1 hormone pathways18.

Rat models provide a powerful method to study the mechanisms behind both the weight and metabolic effects of RYGB. In this paper, we present a RYGB protocol that has low mortality with significant weight loss and metabolic effects. Once the operator became familiar with the technique, the procedure took approximately 90 minutes to perform. The protocol can also be modified with longer biliopancreatic and Roux limb lengths to potentially increase weight loss and metabolic effect. Furthermore, it is technically more feasible than other models as it allows the use of surgical staplers to achieve hemostasis and minimize operative time. Models that rely on sharp division of the stomach without stapling often result in higher mortality due to significant blood loss. The technical skills required to perform the procedure were relatively easy to acquire, and learners were able to comfortably perform the procedure after approximately five to ten non-recovery procedures.

One of the critical steps of this protocol is to limit blood loss during mobilization of the stomach. Careful use of thermal cautery combined with suture ligation of vessels is important. It is also important to perform at least half the circumference of the anastomoses in an interrupted manner. This prevents excessive stricturing at the anastomoses. Furthermore, checking for leaks is crucial as these can lead to sepsis and death. Prior to closing the abdomen, it is essential that the left lobe of the liver is placed in its natural, anterior position and that there is no rotation in the bowel or the stomach as this can lead to visceral ischemia.

Postoperative care is vital to this protocol. Raised wire platforms are required during both fasting and postoperative periods as the consumption of solid material leads to anastomotic obstructions. It is vitally important to provide subcutaneous fluid as the rats may not tolerate oral fluids in the immediate postoperative period. The rats should be acclimatized to oral rehydration therapy and liquid diet as rats may avoid new diets due to associations with postoperative pain. This dietary protocol contributes to significant weight loss in the immediate postoperative period in both the RYGB and sham cohorts, and weight recovery in the sham group took about five weeks. However, strict adherence to this postoperative protocol is vital to reduce morbidity and mortality after RYGB. Additionally, frequent examination of the rats using the Rat Grimace Scale is important to detect for morbidity. In our study, one rat developed a late anastomotic leak which was rapidly detected using this scale and allowed for early euthanasia to reduce suffering.

One of the advantages of this method is that it results in a smaller pouch through the use of surgical staplers to reduce gastric bleeding. When we attempted to sharply divide the stomach without staplers, it leads to excessive bleeding and a much higher mortality rate. However, this also leads to the removal of the forestomach, and this may lead to physiologic changes that are different from that of human RYGB. However, the forestomach is unique to rodents and contains no glands, and should not cause any changes to gut hormones.

The most important limitation of this method is that it requires two surgical stapler reloads per rat, which can be costly. However, excellent survival outcomes potentially reduce cost by requiring less rats for a study, resulting in better utilization of husbandry facilities, surgical equipment and research personnel.

Ujawnienia

Ethicon supplied two 45 mm linear cutting staplers, multiple 3.5 mm stapler reloads, and 6-0 polypropylene sutures. Authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Podziękowania

This study was funded by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Research Award. Ethicon graciously supplied sutures, staplers, and clips. The lead author's doctoral research was funded in by the University of Alberta Clinician Investigator Program and the Alberta Innovates Clinician Fellowship. We would also like to thank Michelle Tran for her medical illustration of the RYGB anatomy.

Materiały

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 2-0 Silk Sutures | Ethicon | K533 | |

| 3-0 Vicryl Sutures | Ethicon | J219H | |

| 4% Isoflurane | N/A | N/A | |

| 5% Dextrose and 0.9% Sodium Chloride Solution - 1000 mL | Baxter | 2B1064 | |

| 50 mL Conical Centrifuge Tubes | Fisher Scientific | 14-432-22 | |

| 6-0 Prolene Sutures | Ethicon | 8805H | |

| Anesthetic Machine | N/A | N/A | |

| Animal Hair Shaver | N/A | N/A | |

| Betadine Solution | N/A | N/A | |

| Castrojievo Needle Holder with lock 14 cm (smooth curved) | World Precision Instruments | 503258 | |

| ECHELON FLEX Articulating Endoscopic Linear Cutter | Ethicon | EC45A | |

| Economy Tweezers #4 | World Precision Instruments | 501978 | |

| ENDOPATH ETS Articulating Linear Cutter 45mm Reloads | Ethicon | 6R45B | |

| Far Infrared Warming Pad Controller with warming pad (15.2 cm W x 20.3 cm L), pad temperature probe, and 10 disposable, non-sterile sleeve protectors | Kent Scientific | RT-0515 | |

| Large Rat Elizabethan Collar | Kent Scientific | EC404VL-10 | |

| Liquid Diet Feeding Tube (150 mL) | Bio-Serv | 9007 | |

| Liquid Diet Feeding Tube Holder (short adjustable) | Bio-Serv | 9015 | |

| Micro Mosquito Forceps | World Precision Instruments | 500452 | |

| Micro Scissors | World Precision Instruments | 503365 | |

| Mouse Diet, High Fat Fat Calories (60%), Soft Pellets | Bio-Serv | S3282 | |

| No. 11 Blade and Scalpel Handle | N/A | N/A | |

| OPMI Vario Surgical Microscope | ZEISS | S88 | |

| Raised Floor Grid | Tecniplast | GM500150 Raised Floor Grid | |

| Rodent Liquid Diet, Lieber-DeCarli '82, Control, 4 Liters/Bag | Bio-Serv | F1259 | |

| Sodium Chloride Irrigation 0.9% Solution - 500 mL | Baxter | JF7633 | |

| Sterile Cotton Swabs | N/A | N/A | |

| Sterile Drape | N/A | N/A | |

| Sterile Towel | N/A | N/A | |

| Thermal Cautery Unit | World Precision Instruments | 501293 |

Odniesienia

- Courcoulas, A. P., et al. Three-year outcomes of bariatric surgery vs lifestyle intervention for type 2 diabetes mellitus treatment. JAMA Surgery. 15213 (10), 1-9 (2015).

- Ardestani, A., Rhoads, D., Tavakkoli, A. Insulin cessation and diabetes remission after bariatric surgery in adults with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 38 (4), 659-664 (2015).

- Casella, G., et al. Ten-year duration of type 2 diabetes as prognostic factor for remission after sleeve gastrectomy. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 7 (6), 697-702 (2011).

- Panunzi, S., De Gaetano, A., Carnicelli, A., Mingrone, G. Predictors of remission of diabetes mellitus in severely obese individuals undergoing bariatric surgery. Annals of Surgery. 261 (3), 459-467 (2015).

- Edelman, S., et al. Control of type 2 diabetes after 1 year of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in the helping evaluate reduction in obesity (HERO) study. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 16 (10), 1009-1015 (2014).

- Mingrone, G., et al. Metabolic surgery versus conventional medical therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: 10-year follow-up of an open-label, single-centre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 397 (10271), 293-304 (2021).

- Thaler, J. P., Cummings, D. E. Minireview: Hormonal and metabolic mechanisms of diabetes remission after gastrointestinal surgery. Endocrinology. 150 (6), 2518-2525 (2009).

- Mingrone, G., Castagneto-Gissey, L. Mechanisms of early improvement / resolution of type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery. Diabetes and Metabolism. 35 (6), 518-523 (2009).

- Arapis, K., et al. Remodeling of the residual gastric mucosa after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or vertical sleeve gastrectomy in diet-induced obese rats. PloS One. 10 (3), 012414 (2015).

- Bruinsma, B. G., Uygun, K., Yarmush, M. L., Saeidi, N. Surgical models of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery and sleeve gastrectomy in rats and mice. Nature Protocols. 10 (3), 495-507 (2015).

- Bueter, M., et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass operation in rats protocol. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. (64), (2012).

- Stevenson, M., Lee, J., Lau, R. G., Brathwaite, C. E. M., Ragolia, L. Surgical mouse models of vertical sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en Y gastric bypass: a Review. Obesity Surgery. , (2019).

- Hao, Z., et al. Reprogramming of defended body weight after Roux-En-Y gastric bypass surgery in diet-induced obese mice. Obesity. 24 (3), 654-660 (2016).

- Adult rodent anesthesia SOP. UBC Animal Care Guidelines Available from: https://animalcare.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/ACC-01-2017_Anesthesia.pdf (2017)

- Sotocinal, S. G., et al. The Rat Grimace Scale: a partially automated method for quantifying pain in the laboratory rat via facial expressions. Molecular pain. , 1-10 (2011).

- Elder, K. A., Wolfe, B. M. Bariatric surgery: A review of procedures and outcomes. Gastroenterology. 132 (6), 2253-2271 (2007).

- Bariatric procedures for the management of severe obesity: Descriptions. UpToDate Available from: https://www-uptodate-com.remotexs.ntu.edu.sg/ (2017)

Przedruki i uprawnienia

Zapytaj o uprawnienia na użycie tekstu lub obrazów z tego artykułu JoVE

Zapytaj o uprawnieniaThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone