Method Article

Saline Lavage for Sampling of the Canine Nasal Immune Microenvironment

In This Article

Summary

Saline nasal lavage can be used to sample the canine nasal immune microenvironment. Because the approach is relatively non-invasive and does not disrupt the nasal tissues, it can be performed serially. Cells and proteins collected from the nasal lavage technique can be processed for various laboratory analyses.

Abstract

Evaluating the local immune microenvironment of the canine nasal cavity can be important for investigating normal tissue health and disease conditions, particularly those associated with local inflammation. We have optimized a technique to evaluate the local nasal immune microenvironment of dogs via serial nasal lavage. Briefly, with dogs under anesthesia and positioned in sternal recumbency, prewarmed sterile saline is flushed into the affected nostril using a flexible soft rubber catheter. The fluid backflow is collected into conical tubes, and this process is repeated. The fluids containing dislodged cells and proteins are pooled, and the pooled nasal lavage samples are filtered through a cell strainer to remove large debris and mucus. Samples are centrifuged and the cell pellets are isolated for analysis. Once the samples have been processed, analyses that may follow nasal lavage include flow cytometry, transcriptomic analysis of cells via bulk or single-cell RNA seq, and/or quantification of cytokines present in the lavage fluid.

Introduction

Dogs routinely develop inflammatory nasal conditions throughout their lives. The underlying cause of acute or chronic rhinitis in dogs can range from infectious (viral: e.g., influenza, parainfluenza, herpesviruses; bacterial [e.g., Bordetella, mycoplasmas], fungal [e.g., aspergillosis, cryptococcosis]; parasitic [e.g., nasal mites]) to neoplastic (e.g., sinonasal malignancies, most commonly carcinoma or sarcoma histotypes) to foreign material (e.g., foreign body, intranasal migration of displaced teeth) to periodontal disease, as well as canine idiopathic inflammatory rhinitis1,2,3,4,5,6,7.

In addition to a physical examination, various approaches are used to evaluate the condition of the sinonasal cavity in dogs with nasal inflammation. Imaging procedures may include radiographs (dental, skull), computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Another approach to imaging the nasal cavity is rhinoscopy. Tissue sampling can involve acquiring nasal swabs, brush samples, or tissue biopsies, from which cytologic and/or histopathologic evaluation can be performed, as well as sample submission for fungal or bacterial culture. These samples may be obtained in a variety of approaches, ranging from "blind" sampling, to image-guided with rhinoscopy or advanced imaging, and acquired through the nares, from the nasopharynx, or with a surgical approach of trephination, rhinotomy, or sinusotomy.

Nasal lavage, which involves administering sterile saline into the nasal cavity, has also been used for sampling the canine nasal cavity for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. An alternative version of the nasal lavage technique that has been used for nasal tumors is termed nasal hydropulsion, described as forceful nasal flushing, which can dislodge large tumor samples for diagnostic evaluation as well as provide therapeutic relief for the improvement of clinical signs associated with the nasal cancer8.

We present here another version of the nasal lavage technique for the intended purpose of collecting and analyzing cells and proteins of the nasal immune microenvironment. Through a gentle, relatively non-invasive approach, we have optimized this nasal lavage technique for serial nasal immune microenvironment sampling. In trials involving dogs with uninflamed nasal cavities, active herpesvirus infection, and sinonasal tumors, we have demonstrated the utility of nasal lavage for the collection and processing of samples for downstream applications9,10.

In this manuscript, we describe a technique of saline nasal lavage for serial sampling of the canine nasal immune microenvironment. We provide protocol details for acquiring the nasal lavage sample effectively with minimal disruption to the tissues and then, processing the samples for a variety of analyses.

Protocol

This nasal lavage procedure has been approved by the Colorado State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Clinical Review Board (IACUC #2425). A schematic of the nasal lavage method is presented in Figure 1.

1. Preparing for the nasal lavage

- The day before the nasal lavage procedure, fill five 20 mL syringes with sterile physiological saline (0.9% sodium chloride solution) and close with a cap. Place the syringes in an incubator set to 37 oC so they can warm overnight.

2. Positioning the dog for the nasal lavage

- Anesthetize the dog for the procedure (e.g., with intravenous (IV) injection of dexmedetomidine (1-4 μg/kg) and butorphanol (0.2-0.5 mg/kg) through an IV catheter), followed by administration of propofol IV (2-5 mg/kg) titrated to effect for intubation; maintain anesthesia with 1-2% inhalant isoflurane to effect.) Confirm the appropriate depth of anesthesia by checking for palpebral response and jaw tone.

- Lubricate the eyes to prevent drying during the procedure.

- Monitor cardiac telemetry, blood pressure, capnography, and pulse oximetry values throughout the procedure.

- Position the anesthetized dog in sternal recumbency. Place the dog's head so that it is angled naturally and comfortably at a downward angle from the edge of the treatment table for optimal nasal lavage sample collection.

- Inflate the cuff of the endotracheal tube to ensure a tight seal of the airway.

3. Performing the nasal lavage

- Cut an 8 FR sterile, red rubber catheter at the base so that it fits snugly onto one of the prefilled 20 mL syringes containing the warm saline. Measure a sterile red rubber catheter so that the distal tip of the catheter will extend to approximately midway into the nasal cavity when introduced through the nostril. If sampling a nasal tumor, use imaging or rhinoscopic guidance to estimate the location of the rostral aspect of the nasal tumor for measuring the length of the red rubber catheter so that the tip will extend to the rostral aspect of the tumor.

- Then, cut the catheter at the tip for the defined intranasal catheter length so that the tip will land in the appropriate location when inserted into the nasal cavity. However, allow additional length for the base of the catheter extending outside of the nostril (catheter length from syringe fixation point to nostril entrance, approximately 3-5 cm). Apply a mark with a permanent marker to the base end of the catheter to indicate the starting point, corresponding to the nostril entrance; the predetermined catheter length will span intranasally, with the catheter tip positioned in the desired location within the nasal cavity.

- Performing the nasal lavage procedure will require the participation of two individuals. Make one person (Person A) responsible for feeding the catheter into the nasal cavity and administering the lavage and the other person (Person B) for collecting the sample as it exits the nose.

- Have Person A position themselves in front and below the dog's head. With gloved hands, have Person A gently guide the tip of the red rubber catheter into the medial aspect of the nasal cavity and advance it until the mark on the catheter lines up with the outer aspect of the nostril. During this process, ensure the catheter is connected to the syringe containing the warmed sterile saline. Have Person B hold a 50 mL conical tube below the nostril with the catheter in place.

- Person A gently occludes the contralateral nostril and begins to infuse the saline into the nasal cavity with slow, steady pressure or with a pulsed infusion. As the dog's head is positioned at a downward angle, Person B collects the fluid that drains out of the nasal cavity via gravity into the 50 mL conical tube.

- Repeat this nasal lavage technique for up to a total of five 20 mL saline lavages, changing out conical tubes, as needed, to collect the pooled samples. Record the total volume of nasal lavage fluid collected relative to the amount of saline infused following completion of the procedure.

- Once completed, if anesthetized with dexmedetomidine, intramuscularly administer the same volume of atipamezole as used for dexmedetomidine, and allow the dog to recover from anesthesia. To be cautious, keep the dog in sternal recumbency with the head positioned downward to facilitate additional drainage of any residual saline from the nasal lavage.

4. Processing the nasal lavage sample

- Gently vortex and/or pipette the nasal lavage samples contained within the conical tubes to break up clumps of debris and cells. Pass the pooled nasal lavage samples through a 70 µm cell straining filter to remove large debris and mucus. Centrifuge the samples at 300 × g for 5-10 min to form a cell pellet.

- Collect the supernatant via aspiration with a pipette and deposit it in a clean tube for analysis of proteins of interest.

- Resuspend cell pellets in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or preferred solution for cell assays of interest.

- To clear red blood cells from the samples, perform ammonium-chloride-potassium (ACK) lysis to collect nucleated cells from nasal lavage11,12.

Results

With this nasal lavage method, the collected sample will appear slightly cloudy, possibly with visible pieces of cellular debris and mucus when the tube is swirled. A sample would be considered contaminated with peripheral blood if the lavage procedure inadvertently induces bleeding, and the sample is tinged red. While some of the infused saline will be lost during the procedure, a negative lavage would be considered if the infused saline does not flow back out of the nostril and into the tube; potential causes could be that the head is not tilted downward sufficiently to allow effective backflow, the sample has drained caudally or laterally out through the contralateral nostril, or the red rubber catheter is not fixed tightly to the syringe and the saline has leaked outwards from the point of connection.

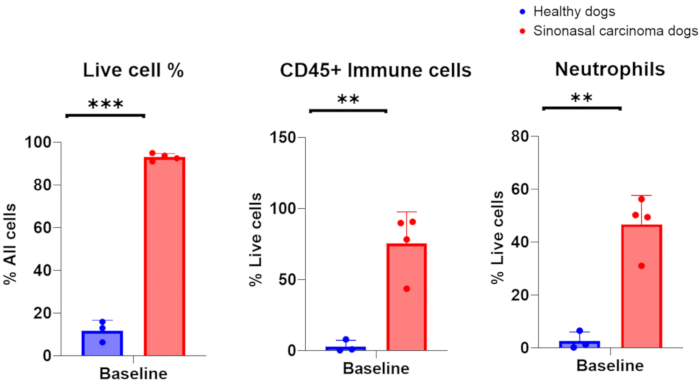

When nasal lavage samples have been collected successfully from dogs with nasal cancer, nucleated cell counts in the range of 1 × 106-200 × 106 are anticipated, with 75-96% live cells. Alternatively, when nasal lavage samples have been collected successfully from dogs with otherwise healthy, non-inflamed nasal cavities, the cell counts have been in the range of 7 × 105-2 × 106, with 6-16% live cells. A representative image of cytologic specimens obtained from nasal lavage sampling of tumor-bearing dogs is featured in Figure 2. Additionally, flow cytometric evaluation of cellular populations analyzed from nasal lavage samples of healthy and tumor-bearing dogs is presented in Figure 3. It would be expected that cell counts and percent viability lower than these ranges would indicate that the nasal lavage procedure and sample collection were unsuccessful. Table 1 summarizes the results of the nasal lavage technique performed by the authors with respect to the number of procedures performed, the number of dogs, the condition of the nasal cavity (healthy or tumor-bearing), the yield of nucleated cell counts, the viability of cells obtained for the procedure, and whether the lavage sample was considered a success or failure for downstream analysis. For the purposes of the experiments performed with the nasal lavage samples included in Table 1, a minimum cell number yield of 150,000 was considered a successful nasal lavage sample collection.

With this nasal lavage technique, sterile 0.9% saline is used to collect the cells. Alternatively, Hartmann's solution (lactated Ringer's solution) could be considered; however, samples collected with either saline or Hartmann's solution would need to be tested to ensure comparable viability and results for the cells of interest. Additionally, an alternative to using a red rubber catheter in non-tumor-bearing dogs could be to perform the nasal lavage with a Foley catheter. While not used in the nasal lavage technique presented here, the use of a Foley catheter would allow inflation of the balloon at the tip of the catheter, occluding the nasal cavity and preventing loss of fluid caudally. Also, while not tested in the nasal lavage processing approach presented here, the addition of hyaluronidase to the nasal lavage sample could be considered to break up the mucus collected in the nasal lavage sample and free more cells for analysis. This would also need to be optimized to ensure results are not altered by the addition of hyaluronidase to the nasal lavage processing procedure.

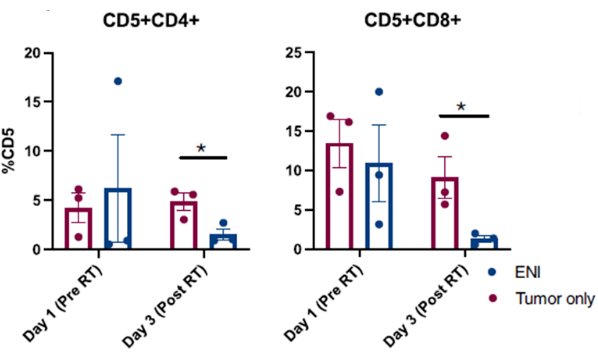

Published results obtained from successful nasal lavage procedures performed in dogs enrolled in a canine cancer clinical trial are presented in Figure 310. The results presented in Figure 3 are from a study investigating the impact of elective nodal irradiation on the local immune microenvironment of dogs with sinonasal tumors whose tumors were either irradiated alone or in combination with regional cervical lymph node irradiation. Through serial sampling of the nasal cavity of dogs in the clinical trial with nasal lavage, flow cytometric analysis of cells collected revealed a significant decrease in the populations of effector T cells on the last day of radiotherapy when regional lymph nodes were irradiated concurrently with the sinonasal tumor compared to dogs who received radiotherapy targeted to the tumor and the regional lymph nodes were spared. This demonstrates the utility of serially sampling the nasal cavity with lavage to investigate shifts in cell populations at different points and with different treatment conditions.

Figure 1: Schematic of the nasal lavage method. Warmed, sterile saline is infused into the nasal cavity of anesthetized dogs using a red rubber catheter. The nasal lavage fluid is collected into a tube as it drains out of the nose. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Cellular composition of a nasal lavage sample collected from a dog with a nasal tumor. Representative image of cytologic specimens obtained from nasal lavage sampling (500x magnification, Modified Wright-Giemsa stain). Neutrophils (arrows) are the predominant cells, with a few squamous epithelial cells (arrowhead) and small mature lymphocytes (highlighted in the square box) also present. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3. Flow cytometric analysis of nasal lavage samples collected from healthy and tumor-bearing dogs. Comparison of abundance of live cells, immune cells, and neutrophils between healthy dogs (blue, n = 3) and tumor-bearing dogs with sinonasal carcinoma (red, n = 4). Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: Flow cytometric analysis of cells collected from nasal lavage from dogs enrolled in a clinical trial investigating the impact of elective nodal irradiation (ENI) on the local immune microenvironment. Quantification of CD4 (CD5+CD4+) and CD8 (CD5+CD8+) T cells from nasal lavage samples. Dogs treated with ENI concurrently with tumor irradiation (n = 3) had significantly reduced effector CD4 and CD8 T cells on the final day of radiation (Day 3) compared to dogs treated with radiation targeted to the tumor alone (n = 3). This figure was modified from Darragh et al.10. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| Healthy (n=3) | Tumor bearing (n= 19) | |

| Number of procedures performed | 3 | 80 |

| Cell count | 0.7 x 106 - 2.8 x 106 | 1.6 x 106 - 210 x 106; median: 8.7 x 106 |

| Cell viability | 6.3 - 15.9% | 75% - 96%; median: 87% |

| Success rate | 100% | 98.80% |

Table 1: Summary of nasal lavage procedures performed and cellular characteristics of samples obtained.

Discussion

There are several critical steps in the nasal lavage protocol. With respect to the dog undergoing the nasal lavage procedure, the dog must be within a deep enough plane of anesthesia so that they do not react to the catheter placement or lavage administration. If they are reactive under anesthesia, this may compromise the quality and quantity of lavage sample collection, as well as potentially increase risks for acute nasal tissue injury due to local trauma from the intranasal catheter or for the dog aspirating the lavage fluid.

Positioning of the dog's head is also critical for optimal nasal lavage sample collection. If the downward angle of the head is insufficient for gravity-dependent backflow of the instilled saline, the nasal lavage fluid may flow caudally, and the sample could be lost through the nasopharynx. Additionally, clear communication between Person A and Person B is important during the nasal lavage procedure. Quick adjustments may be required by Person B for collection tube placement as the fluid is draining from the nostril while Person A is flushing; visibility of the lavage fluid flowing into the conical tube may not be entirely clear for both Person A and Person B during the procedure, so active communication throughout the process is key for successful sample collection. Once the nasal lavage sample has been collected, if cell viability is to be preserved for future analysis, it is critical that cells are maintained in a physiologic pH solution, such as 0.9% saline or 1x PBS.

Modifications can be made to the nasal lavage protocol throughout the collection and processing phases. During sample collection, the depth of anesthesia may be adjusted to ensure the dog will not react to the nasal lavage. This may be achieved by adjusting the percentage of the anesthetic gas (e.g., isoflurane) or administering a bolus of short-acting intravenous anesthetic (e.g., propofol).

If after the instillation of the saline into the nasal cavity, only a small amount of the fluid is collected in the tube, reposition the dog's head at a downward angle, so that it is resting comfortably off the edge of the table, to increase the potential for gravity to allow the fluid to drain from the nose. If it is noted that fluid is draining from the contralateral nostril, tightly occlude the contralateral nostril for the following lavages. During the processing phase, if the initial sample cell count is low, re-centrifuge the supernatant portion of the sample to collect any additional cells that may be present to increase the total yield.

There are notable limitations to utilizing the nasal lavage method to analyze the canine nasal immune microenvironment. With this technique, the nasal lavage samples are a collection of surface cells and proteins from the nasal cavity that are easily dislodged. These surface cells and proteins may not be entirely representative of the deeper tissues of the canine nasal microenvironment. Efforts are underway to compare the cellular and protein profiles of canine nasal lavage to biopsy samples to determine the similarities and differences in these factors between the two nasal cavity sampling techniques.

Despite these limitations, the nasal lavage technique for sampling the canine nasal immune microenvironment provides an alternative approach to existing methods. When compared to a tissue biopsy or even a rhinoscopy procedure, nasal lavage is relatively non-invasive for the canine patient. Gathering cells and proteins via nasal lavage compared to tissue biopsy decreases risks for clinically concerning, prolonged, or significant acute hemorrhage; following the nasal lavage procedure, there is also likely less local inflammation and discomfort when compared to a nasal tissue biopsy. Because of this, nasal lavage may be performed serially to gather multiple samples over time for analyses. Additionally, there is increased relative ease in processing the nasal lavage samples compared to tissue biopsy samples with respect to separating the cellular component from the proteins within the supernatant for downstream laboratory methods and assays.

The nasal lavage method has the potential for important applications in research areas associated with the immune microenvironment. In cancer research, the nasal lavage technique has been used10 and can be used to document serial changes in the nasal cavity microenvironment in tumor-bearing dogs relative to treatment conditions; these nasal lavage samples may also prove to be valuable in correlating shifts in the immune microenvironment to better understand responses to cancer treatment. Similar aspects of investigating serial changes in the nasal immune microenvironment may be explored and investigated for numerous veterinary clinical and translational infectious and inflammatory research areas.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

The canine nasal lavage technique described herein has been optimized through projects supported by K01 OD03109, CCTSI Colorado Pilot Grant Award, CSU CVMBS College Research Council Shared Resources Program, and CO HNC SPORE CA261605: Career Enhancement Program. Figure 1 was created with BioRender.com.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 1.5 mL Tubes | Eppendorf | 05-402 | |

| 1000 µL Pipette | VWR | 89079-974 | |

| 1x PBS | Corning | 21-040-CV | |

| 20 mL Syringes | VWR | BD302830 | |

| 50 mL Conical Tubes | VWR | 89039-656 | |

| 70 µm Cell Strainer | Fisherbrand | 22-363-548 | |

| 8FR Sterile Red Rubber Catheter | Med Vet International | 50-252-2428 | |

| ACK Lysis Buffer | Gibco | A1049201 | |

| Centrifuge | Beckman Coulter | 366816 | |

| Physiological Saline (0.9%) | Vetivex | 17033-492-01 | |

| Vortex | VWR | 10153-838 |

References

- Cohn, L. A. Canine nasal disease: An update. Vet Clin: Small Anim Pract. 50 (2), 359-374 (2020).

- Mortier, J., Blackwood, L. Treatment of nasal tumours in dogs: A review. J Small Anim Pract. 61 (7), 404-415 (2020).

- Plickert, H., Tichy, A., Hirt, R. Characteristics of canine nasal discharge related to intranasal diseases: A retrospective study of 105 cases. J Small Anim Pract. 55 (3), 145-152 (2014).

- Windsor, R. C., Johnson, L. R. Canine chronic inflammatory rhinitis. Clin Tech Small Anim Practice. 21 (2), 76-81 (2006).

- Van Pelt, D. R., Mckiernan, B. C. Pathogenesis and treatment of canine rhinitis. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 24 (5), 789-806 (1994).

- Hazuchova, K., Neiger, R., Stengel, C. Topical treatment of mycotic rhinitis-rhinosinusitis in dogs with meticulous debridement and 1% clotrimazole cream: 64 cases (2007-2014). JAVMA. 250 (3), 309-315 (2017).

- Lobetti, R. Idiopathic lymphoplasmacytic rhinitis in 33 dogs. JS Afr Vet Assoc. 85 (1), 1-5 (2014).

- Ashbaugh, E. A., Mckiernan, B. C., Miller, C. J., Powers, B. Nasal hydropulsion: A novel tumor biopsy technique. JAAHA. 47 (5), 312-316 (2011).

- Wheat, W., et al. Local immune and microbiological responses to mucosal administration of a liposome-tlr agonist immunotherapeutic in dogs. BMC Vet Res. 15 (1), 330 (2019).

- Darragh, L. B., et al. Elective nodal irradiation mitigates local and systemic immunity generated by combination radiation and immunotherapy in head and neck tumors. Nat Commun. 13 (1), 7015 (2022).

- Pinard, C. J., et al. Evaluation of lymphocyte-specific programmed cell death protein 1 receptor expression and cytokines in blood and urine in canine urothelial carcinoma patients. Vet Comp Oncol. 20 (2), 427-436 (2022).

- Choi, J. W., et al. Development of canine pd-1/pd-l1 specific monoclonal antibodies and amplification of canine t cell function. PLoS One. 15 (7), e0235518 (2020).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved