Method Article

Transmission Electron Microscopy: A Surgical Pathology Tool for Neuroblastoma

* These authors contributed equally

In This Article

Summary

Pediatric small round blue cell tumors are an intriguing and challenging collection of neoplasms. Therefore, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and professional knowledge of pediatric tumors can be extremely valuable in surgical pathology. Here, we present a protocol to perform TEM for diagnosing neuroblastoma, one of the most common solid tumors in childhood.

Abstract

Pediatric small round blue cell tumors (PSRBCT) are an intriguing and challenging collection of neoplasms. Light microscopy of small round blue cell tumors identifies small round cells. They harbor a generally hyperchromatic nucleus and relatively scanty basophilic cytoplasm. Pediatric small round blue cell tumors include several entities. Usually, they incorporate Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, retinoblastoma, lymphoma, and small cell osteosarcoma, among others. Even using immunohistochemistry, the differential diagnosis of these neoplasms may be controversial at light microscopy. A faint staining or an ambiguous background can deter pathologists from making the proper diagnostic decision. In addition, molecular biology may provide an overwhelming amount of data challenging to distinguish them, and some translocations may be seen in more than one category. Thus, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) can be extremely valuable. Here we emphasize the modern protocol for TEM data of the neuroblastoma. Tumor cells with tangles of cytoplasmic processes containing neurosecretory granules can diagnose neuroblastoma.

Introduction

The work of a pathologist may be pretty challenging both in clinical diagnostics and research fields. The evolution of light microscopy in the 18th and 19th century was remarkable. The power of an electron microscope relies primarily on the wavelength of the electrons, which is shorter than light1,2,3. Before the advent of the polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies and their application in immunohistochemistry, TEM played an influential role in diagnosing small round blue cell tumors.

Starting with the 90's of the last century, the immunohistochemical approach has substituted the morphologic tool in diagnostics4. Currently, there are thousands of new polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies directed to antigens of the small round blue cell tumor group4,6,7,8. In the last decade of the highly prolific 20th century and the first decade of the beginning of the 21st century, molecular biology, including fluorescence in situ hybridization, from genomic probes through next-generation sequencing, seems to have superseded the significant application role of immunohistochemistry in several laboratories4. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States of America, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) of Canada, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), or similar governmental bodies in other countries do not always approve molecular biology protocols9. It seems that there is a lot of information quite challenging to insert in a pathology report that can be used for therapeutic purposes, and the oculate choice of a well-funded and running laboratory information system is critical10. In the meantime, immunohistochemistry has revealed numerous pitfalls, with epithelial tumors showing mesenchymal markers and vice versa11. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition has confused some borders in pathology groups12,13. In the last few years, it has become evident that electron microscopy flourished in several labs worldwide14. In particular, the tissue specimens' turnaround time has decreased from weeks to only 3 days or even less using several protocols approaching the staining with monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies4,10.

Moreover, applying an electronic camera coupled to the electron microscope helped provide the pathologists with a rapid image, which is versatile in different operating systems. Finally, some antibodies, even after antigen retrieval, are challenging to be revealed in some areas of necrosis or autophagy/ischemia-related changes. At the same time, electron microscopy in safe hands can still deliver excellent results and hints for the correct classification of unknown pathologic tumors15.

The pediatric small round blue cell tumor group includes several tumors, mainly neuroblastoma, Wilms tumor or nephroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma. The molecular biology data relative to the pediatric group of small round blue cell tumors can be overwhelming because of the techniques applied. The small round blue cells may not differ much on routine stains (hematoxylin and eosin staining), and some tumors may have aberrant immunophenotypical features. Advances in molecular biology have been enormous since the discovery of TEM. In the group of small round blue cell tumors, some neoplasms may be more frequently encountered than others, but they need to be considered. Although the papillary renal cell carcinoma is not essentially a small round blue cell tumor but features papillae mostly, it may show some round cell areas that may need to be distinct from other well-known small round blue cell tumors (e.g., Wilms tumor) using several ancillary techniques16. Ultimately, metanephric stromal tumors may also need to be taken into differential diagnosis17. The rhabdoid tumor is a particularly malignant pediatric tumor distinct in the renal and extra-renal subtype18.

Neuroblastoma is one of the most common solid malignancies in infancy and childhood. Neuroblastoma cells are the malignant cells of this solid tumor that arise insidiously from derivatives of the primordial neural crest. Its diagnosis and differential diagnosis may be difficult. Its natural biology has seen remarkable advances in the last couple of decades. The forkhead family of transcription factors is characterized by a distinct "forkhead" domain (FOXO3/FKHRL1). These transcription factors function as a trigger for apoptosis (programmed cell death) through the expression of genes necessary for cell death. FOXO3/FKHRL1 is activated by 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine and induces silenced caspase-8, and this complex plays a crucial role in neuroblastoma. Nuclear FOXO3 predicts adverse clinical outcomes and promotes tumor angiogenesis in neuroblastoma7,19. Despite the molecular pathology advances, the Shimada classification remains the standard of practice for any pathologist and pediatric oncologist. It is critical in differentiating between favorable and unfavorable histology20,21,22,23.

The rationale for developing a straightforward protocol for the electron microscopy of tumors suspicious of neuroblastoma is linked to the feasibility and solidity of the ultrastructural examination of the tissue specimen. It is rarely altered by problems commonly encountered using immunohistochemistry. The rationale and protocol have been the basis of several textbooks and scientific contributions to pediatric pathology and electron microscopy4,24,25. This protocol spans the experience of three decades of the author and will focus on a few PSRBCT, emphasizing the personal experience and the literature review.

Protocol

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The electron microscopy study is part of the normal routine for microscopic investigation of the samples received for diagnostic purposes and does not require approval by the Bioethics Committee. This study is retrospective and respects the complete anonymity of the samples.

1. TEM protocol for FFPE (formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded) retrieval and glutaraldehyde-fixed tissue specimens

- Retrieve the last hematoxylin- and eosin-stained slides and the FFPE tissue block.

- With a permanent marker, select the area of interest on the tissue slide and match it to the area on the tissue block.

- Cut out the selected area with a new razor blade from the block and accurately cut it into 5 mm cubes on filter paper.

- Place the filter paper with the retrieved tissue in a labelled petri dish. Lodge the petri dish in a 60-70 °C oven for 15 min, i.e., until the paraffin melts (paraffin wax consists of a mixture of solid straight-chain hydrocarbons ranging in melting point of 48 °C-66 °C (120 to 150 °F)) and gets absorbed by the filter paper.

- Transfer the retrieved tissue free of paraffin into a scintillation vial filled with 4 mL of 100% toluene (methylbenzene) v/v [100% toluene means 100 mL of toluene]. Ensure that the samples continuously rotate through the deparaffinization process (Rotation speed: 24 rotations/min).

- Go through two changes of toluene, 1 h each, and one change of 4 mL of 100% toluene 30 min each, using an angled rotating device.

- Proceed through one change in 4 mL of 100% absolute ethanol (C2H5OH) for 1 h, and then two changes of 4 mL of 100% absolute ethanol for 30 min each. Then, another change of 30 min in 4 mL of 70% ethanol.

- Proceed through one change of 4 mL of 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, 30 min. Transfer the specimens in 4 mL of 2.5% glutaraldehyde and keep at 4 °C until processing.

- Use the following steps in an automated tissue processor to standardize the processing: 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 5 min, 2% osmium tetroxide for 1 h and 50 min, dH2O for 5 min, 50% ethanol for 15 min, 70% ethanol for 30 min, 100% ethanol for 15 min (three times), 100% ethanol for 30 min (three times), 100% ethanol for 45 min, acetone for 50 min, resin for 1 h (two times), and fresh resin overnight. The volume of all solutions is 15 mL.

- Embed with fresh resin right out of the tissue processor.

- Position polyethylene capsules in a holder with numbered strips of paper. Drop fresh resin in the capsules, transfer the specimen to the appropriate blocks and keep the blocks overnight in a 60 °C (140 °F) oven.

- Stain semi-thin (500 nm) sections with 1% toluidine blue on the hot plate, minimum heat setting for 30 s, rinse in dH2O, and then place a coverslip.

- Here, the Ultracut microtome (UCM) is used for sectioning semi-thin sections.

- Take resin embedded block and install it in the block holder of the UCM. Then, install the block holder on the stage of the UCM and tighten it.

- Cut excess resin around the sample using a single edge coated razor blade using the oculars. Cut the face of the block in a trapezoidal shape.

- Remove the block holder from the stage and install it in the UCM arm, tight. Next, install the blade holder on the UCM stage. Finally, tighten a glass knife on the blade holder.

- Using the oculars and the light provided by the UCM, slide the edge of the glass knife slowly, as close as possible, to the surface of the resin block to cut. Tighten the blade holder in place on the stage.

- Set the cutting thickness of the UCM at 500 nm and trim the resin block until 75% full-faced.

- Change the glass knife to a new one. Add sterile water to the glass knife's reservoir.

- Label a microscope slide with the case number and put four separate drops of sterile water on the glass slide.

- Still at 500 nm setting, cut four sections from the block. Using fine forceps, transfer 1 section at a time in one of the drops of water on the glass slide. Each drop on the slide will contain one section. Dry the slide on a hot plate at the lowest heat setting until dry (30 s).

- Stain with the Toluidine blue method. Rinse in water and place a coverslip. Examine toluidine blue sections under a light microscope. If desired tissue structures are visible, cut ultra-thin sections. If desired tissue structures are not visible, cut deeper sections and stain them using the same steps until desired structures are exposed and shown on the toluidine blue slide.

- When the desired area for electron microscopy is identified from the toluidine blue sections, cut the ultra-thin sections on the copper grids. Cut ultrathin slices using an ultramicrotome (samples destined for viewing in the TEM must be cut into very thin slices (80 nm)).

- Take resin embedded block and install it in the block holder of the UCM. Then, install the block holder on the stage of the UCM and tighten it.

- Using the oculars, cut the resin around the desired area for electron microscopy using a single-edge coated razor blade. Cut the face of the block in a trapeze shape, no bigger than 1 mm square. If the desired area for electron microscopy is challenging to see because of the glare of the light, use a dab of chloroform to highlight the structures in the resin block.

- Remove the block holder from the stage and install it in the UCM arm, tight. Next, install the blade holder on the UCM stage. Finally, tighten a diamond knife on the blade holder.

- Using the oculars and the light provided by the UCM, slide the edge of the diamond knife slowly, as close as possible, to the surface of the resin block to cut. Tighten the blade holder in place on the stage.

- Adjust the different angles of the diamond knife using the screws of the UCM. Ensure that the edge of the diamond knife is aligned as perfectly as possible with the surface of the block to cut. Fill the diamond knife's reservoir with sterile water.

- Set the UCM at 80 nm thickness and 1 mm/s speed. Here, the automated function is used for ultra-thin sectioning. Set the window of cutting on the UCM (top and bottom of the block's face).

- Press the Start button of the UCM to start sectioning. The sections will float on the sterile reservoir of the diamond knife.

- When enough sections are cut, use chloroform fumes to straighten the sections. Dip a cotton swab in chloroform and pass it above the sections without touching them.

- Dip a copper grid in 100% alcohol and then sterile water using fine forceps. Clean each grid before being used. Pick the sections on a few grids.

- Leave the grids with sections on labeled filter paper. Place this filter paper in a Petri dish and put it in the 60 °C oven for 30 min to allow the sections to dry on the grids.

- Then, perform the contrast staining.

- Stain the grids in uranyl acetate or any environment-friendly alternative substitutive for 1 min. Then, rinse them in sterile water for injection (40 dips in four different water containers for each rinse after uranyl acetate and lead citrate). Lead citrate step is also 1 min.

- Insert the grid in the TEM, allowing a high voltage electron beam to be emitted by a cathode and created by magnetic lenses. The beam that has been partially transmitted through the thin (electron-semitransparent) specimen forms the TEM information on the screen (see below).

2. TEM protocol for scanning and photographing the specimens

- After the sections on the grids are stained, screen them with the electron microscope. At the electron microscope, turn on the ACC voltage to a pre-established setting (200-300 kV), which depends on the electron microscope used.

- At the computer, turn on the digital camera software and enter the case number. This is important because the microphotographs are saved in the corresponding case file.

- Load the grid in the electron microscope, pull the gun sample halfway out and flip the switch to AIR to allow the vacuum from the specimen gun chamber to fill with ambient (room) air.

- Once it is full of air, pull out the gun sample. Place the gun sample on the designed holder. Then, flip open the grid holder at the tip of the gun.

- Place the grid in place. Close the grid holder and ensure that the grid is secured.

- Put the gun sample back in the specimen chamber halfway through and flip the switch to EVAC to create a vacuum in the specimen chamber.

- The green light indicator will turn on when the vacuum is achieved in the specimen chamber. Then, push the gun sample carefully into the electron microscope column and make sure not to allow it to go too fast. Otherwise, it would damage the object at the tip of the gun sample.

- Once the grid is well in place in the electron microscope column, turn on the filament to the intermediate (pre-established) saturation setting.

- Turn on the camera through the ON/OFF switch. On the computer, click on Live Image in the imaging software.

- On the electron microscope, push the Low Magnification button and open the objective aperture. This allows for choosing the desired screening area. Next, position the desired area of the section to the middle of the computer screen, using the two controllers on either side of the electron microscope's column.

- On the electron microscope, push the Zoom button and close the objective aperture to obtain better contrast.

- Start the screening of the section by taking microphotographs at 2,500x magnification. Then, adjust the focus using the wobbler button and the brightness button on the electron microscope to ensure the quality of the microphotograph.

- Click on Final Image on the computer to take the microphotograph. If the colors are not even, perform a background correction on the camera software. Also, adjust the contrast on the final image using the software before saving the microphotograph.

- When the microphotograph is being saved, double-check the case number and magnification to ensure proper identification of the microphotographs taken.

NOTE: In some cases, the user can also enter extra captions, and the electron microscopy technologist's initials are also entered. - Perform the micrograph process through the whole area of the section to be screened. After enough 2,500x magnification, microphotographs are saved to cover the area of interest, capture 4,000x and 8,000x magnification microphotographs and save them on the computer with the appropriate case number identification.

- Make a close-up on the section for specific ultrastructural details if very specific screening instructions are given. Then, save the measurements of specific ultrastructural details in the computer considering higher magnifications if needed.

- When the specimen screening is complete, turn off the filament, the camera, the high voltage, and the camera software in sequence. Next, remove the grid from the electron microscope column, allowing air in the gun sample chamber.

- File the grid in a gelatin capsule and store the capsule in a properly labeled box, along with the resin blocks of the same case. Put the gun sample back in the gun chamber and store it in a cool and dry environment to preserve the material used.

- Transfer the digital microphotographs on common collaborative platforms (e.g., SharePoint) or internal servers to allow the pathologist to view them.

- Enter the work units in the Laboratory Information System (LIS).

- If more specific microphotographs are required, pull out the field grid and reuse them for additional screening or specific questions.

Results

The distinctive TEM Features of the neuroblastoma are displayed here. Here we will illustrate the distinctive TEM features of the neuroblastoma.

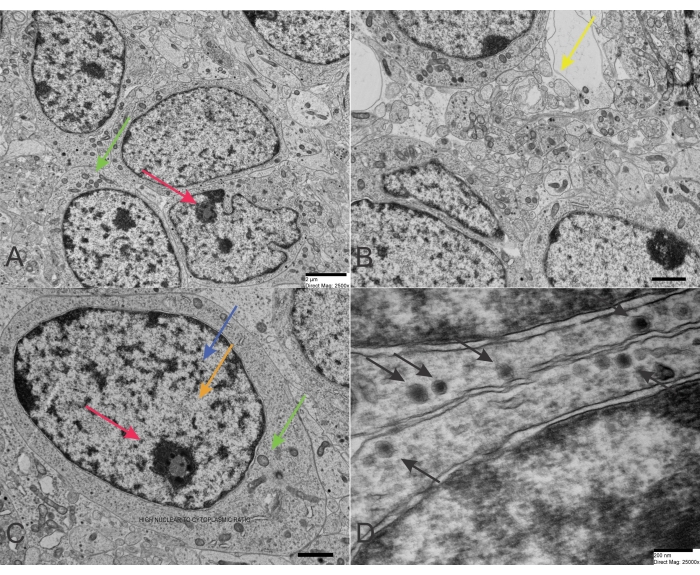

Neuroblastoma is one of the most common solid malignancies in infancy and childhood. Neuroblastoma cells are the malignant cells of this solid tumor that arise insidiously from derivatives of the primordial neural crest. This histogenesis explains some biochemical and morphological characteristics of this blue tumor. However, neuroblastomas' deterministic cyto- and histopathological features can specifically fluctuate according to the variable degree of differentiation. Therefore, its diagnosis and differential diagnosis may be difficult. The distinction of neuroblastoma to ganglion cell-like elements is shown by an increasing amount of cellular cytoplasm with the development of a cytoplasmic process and an alteration of the nuclear image (Figure 1A-D). Nuclear enlargement and a visible nucleolus are characteristic of neuroblastoma differentiation. Differentiation to Schwann cell-like elements may also be noticed. The electron microscopic investigation reveals neurosecretory granules (average diameter 100 nm) constantly present with or without neurite-like cytoplasmic projections containing microtubules and thin intermediate filaments26. The paucity of glycogen characterizes neuroblastoma, and if it is rarely seen, it never builds aggregates. The degree of differentiation distinguishes the ultrastructure of neuroblastoma. Neurosecretory or catecholamine granules are characteristic of this neoplasm, with a diameter of about 150 nm. The neurosecretory granules need to be differentiated from desmosome-like structures. Neurosecretory granules can be seen close to intracytoplasmic filaments (neurofilaments). The cell processes are often plump and cylindrical and are commonly referred to as neurites (axons and dendrites). Some cell processes contain mitochondria, which are critical for the movement of the neoplastic cell. Neurites contain microtubules but also may have swollen mitochondria. In the event of a poorly differentiated neuroblastoma, some features are more often to be found. They include a more significant irregularity of nuclear morphology, numerous mitoses and apoptotic figures, paucity of microtubules and cell processes, contrasting with the almost constant presence of neurofilaments, scarcity of neurites, which contain more often mitochondria than microtubules, no or very few synaptic junctions, no glycogen, areas of numerous polyribosomes, and paucity of neurosecretory granules. Neurosecretory granules are critical to differentiate neuroblastoma from other PSRBCT, including embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, eosinophilic granuloma, small cell osteosarcoma, and reticulum cell sarcoma, which may cause diagnostic challenges because of the presence of cytoplasmic granularity.

Figure 1: TEM of Neuroblastoma. (A-C) Neuroblastoma cells of a poorly differentiated type with a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio and a few organelles. The chromatin is scattered in the nucleus but also concentrated at the periphery close to the nuclear membrane. A nucleolus is visible in a nucleus in the upper-right corner (scale bar: 2 µm). (D) Neuroblastoma cells with neurosecretory granules exhibiting a characteristic double membrane (scale bar: 200 nm). Red arrows point to the nucleoli, blue arrows reveal heterochromatin, orange arrows detect euchromatin, green arrows focus on mitochondria, and yellow arrows point to vesicles resembling the normal presynaptic terminals. However, the vesicles in neuroblastoma are larger and more irregular than the classic presynaptic terminals. Finally, the black arrows reveal numerous dense-core neurosecretory granules. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

In this narrative review with associated protocol, we highlighted the distinctive ultrastructural features of the neuroblastoma. In the end, we suggest that electron microscopy is far from a "dead" or ancient technique, postulating the discovery of a new role if combined with single-cell omics technologies. This contribution would like to emphasize the never ancient role of electron microscopy in pediatric pathology4,27. The critical steps, the modifications and troubleshooting of the technique, and the limitations are detailed below.

There are a few critical steps to this protocol. First, it is essential to cut the desired area for electron microscopy. The edge of the diamond must be adjusted to face the face of the block as close as possible. This requires a very steady hand. Care should be taken while picking up the floating section with the copper grids.

Modifications and troubleshooting of the technique include a few aspects that need to be taken into account. Every sample is different with qualities, such as density and nature, which are variable. Given the nature and density of the material, not all tissue specimens are cut in the same way. For instance, some neuroblastoma specimens may be undifferentiated or poorly differentiated, while others may reveal a high degree of differentiation and a variable degree of calcifications. Occasionally, multiple sections have to be cut to get a few good ones to be processed further. It is crucial to avoid any kind of vibrations: breathing, table, compressors from the EM scopes. If shattering on the sections is encountered, it may be key to tighten the UCM screws. If scratches are seen on the sections, change the diamond knife to be used for cutting. Sometimes, cutting artifacts are only seen at the final step. If cutting artifacts are detected under the electron microscope, ultra-thin sections have to be recut after identifying the cause of the artifact.

TEM has obvious limitations, and the window of observation is even smaller than the view captured using conventional light microscopy. The desired area for the electron microscopy cannot be bigger than a 1 mm square. Sometimes, a bigger area would benefit the screening, but it is impossible to cut. It will not fit on the copper grid, it will damage the diamond knife, and the quality of the section will definitely be inferior. Some choices have to be made, and the most important structure or area at the time of the screening has to be chosen. The cutting speed cannot be increased; it will cause cutting artifacts on the sections. The 1 mm/sec remains critical.

In addition to the classic features listed above (e.g., neurosecretory granules), the ultrastructure of mitochondria in neuroblastoma cells examined by TEM often shows remarkable levels of mitophagy, a mitochondrial quality control selective cellular mechanism enabling the degradation of mitochondria, which are considered by the cells to be damaged and/or superfluous28,29. As a result, the mitochondria harbor swelling, cristae rupturing, and cristae disappearance. In fact, Radogna et al. found efficient mitophagy as the critical mechanism leading to the failure of activation of the pathway of programmatic cell death that increased resistance of SK-N-AS, a neuroblastoma cell line with enhanced synthesis of Insulin-like growth factor II (IFG-II) and IGF-II RNA and harboring type I IGF receptors to UNBS1450, a hemi-synthetic cardenolide belonging to the cardiac steroid glycoside family, triggering necroptosis at somewhat higher doses30.

Particularly relevant to the differential diagnosis is the role of TEM for Ewing sarcoma. The Ewing sarcoma is considered equivalent to peripheral neuroectodermal cell tumor, although some debate has been spent in the past31,32,33. Practically, in the Ewing sarcoma primitive cells, abundant cytoplasmic glycogen, poorly developed cell junctions, and no neural features are the main characteristics. There is a striking similarity in the peripheral neuroectodermal tumor to Ewing sarcoma on electron microscopy. In fact, both tumors are considered the same entity and are treated with the same therapeutic protocols in both SIOP (International Society of Pediatric Oncology) and COG (Children's Oncology Group) as well as the UKCCSG (United Kingdom Children Cancer Study Group) because they share the same chromosomal translocation. However, in PNET, some neural features exist, including neurosecretory granules that are virtually absent in Ewing sarcoma. This specification also reflects the immunohistochemical phenotype. There is positivity for at least one or two neural markers, e.g., neuron-specific enolase, S-100, synaptophysin, or neurofilaments. Franchi et al. studied the ES-PNET31. In most cases, neoplastic cells had the typical ultrastructure, including firmly packed, poorly differentiated cells, oval to polygonal shape. These cells contain a round or oval nucleus with finely dispersed chromatin and one or two nucleoli. In the cytoplasm, tiny organelles mirroring these neoplastic cells' poor differentiation. However, the close attention to detail may reveal the presence of mitochondria, a few rough endoplasmic reticulum structures (the so-called cisternae), sporadic lysosomes, and free ribosomes. Glycogen accumulation may be easily detected. Glycogen can be seen as either dispersed or pooled. Intermediate filaments are often observed in both the cytoplasm and cytoplasmic processes of the tumor cells. Microtubules are not seen. Rudimentary junctions may be detected in about half of the cases about the cell connections. These structures are made of well-developed desmosomes with tonofilaments if the junctions are identified. Some accumulation of basement membrane-like material and collagen fibrils in the extracellular matrix can be recognized. Dense core granules with a diameter similar to the granules seen in neuroblastoma can be observed. Like the immunohistochemical investigations of the previous authors31, well-differentiated neoplasms tend to occur outside of the skeleton, while poorly differentiated tumors arise more often in bone than in soft tissue.

In conclusion, TEM is an outstanding technology that can have enormous potential in the future and is far from dead in medicine. The introduction of molecular biology techniques with the most recent advancement with next-generation sequencing highlights the inconsistency of a continuum in diagnostics but a Kangaroo-like wave of progress. Introducing new methods should not dissuade pathologists from using electron microscopy consistently because both the immunohistochemistry and molecular techniques can be fallacious. Some immunohistochemical patterns and genetic abnormalities are not tumor-specific and may correlate poorly with histology. To our knowledge, TEM remains a robust, valid, and reproducible method in pathology and medicine. TEM is an ancillary tool for investigating small round blue cell tumors and is a solid proof of the immunohistochemical result. Applying TEM consistently in a modern facility can provide a high interindividual agreement score, high validity, and efficient reliability. In the near future, molecular biologists may search for competent and valid laboratories of electron microscopy that may answer specific questions at the ultrastructural level. In particular, we see a new perspective and application of TEM in molecular biologies, such as the coupling of TEM with experiments aiming to understand some current single-cell research.

Disclosures

The first author receives royalties from the following publishers: Springer (https://link-springer-com.remotexs.ntu.edu.sg/book/10.1007/978-3-662-59169-7; ISBN: 978-3-662-59169-7) and Nova (https://novapublishers.com/shop/science-culture-and-politics-despair-and-hopes-in-the-time-of-a-pandemic/; ISBN: 978-1-53619-816-4). All royalties go to pediatric charities.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledged the expertise and generous support of Dr. Richard Vriend, formerly an Alberta Health Services employee at the University of Alberta Hospital, and Steven Joy (1972-2019), also formerly an Alberta Health Services employee at the University of Alberta Hospital. We dedicate this work to the memory of Mr. Joy, a senior technologist expert in ultrastructural investigations who tragically and prematurely passed away a few years ago. Mr. Joy was a pillar for most electron microscopy studies in Alberta, Canada. Our thoughts and prayers for him and his family. We are also indebted to Ms. Lesley Burnet for her help and advice. Dr. C. Sergi's research has been funded by the generosity of the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Ontario, and the Stollery Children's Hospital Foundation and supporters of the Lois Hole Hospital for Women through the Women and Children's Health Research Institute (WCHRI, Grant ID #: 2096), Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province for Hubei University of Technology (100-Talent Grant for Recruitment Program of Foreign Experts Total Funding: Digital PCR and NGS-based diagnosis for infection and oncology, 2017-2022), Österreichische Krebshilfe Tyrol (Krebsgesellschaft Tirol, Austrian Tyrolean Cancer Research Institute, 2007 and 2009 - "DMBTI and cholangiocellular carcinomas" and "Hsp70 and HSPBP1 in carcinomas of the pancreas"), Austrian Research Fund (Fonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung, FWF, Grant ID L313-B13), Canadian Foundation for Women's Health ("Early Fetal Heart-RES0000928"), Cancer Research Society (von Willebrand factor gene expression in cancer cells), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Omega-3 Fatty Acids for Treatment of Intestinal Failure Associated Liver Disease: A Translational Research Study, 2011-2014, CIHR 232514), and the Saudi Cultural Bureau, Ottawa, Canada. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Acetone, ACS Reagent | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 10014 | Reagent as established by the American Chemical Society (ACS Reagent). |

| Automated tissue processor | Electron Microscopy Sciences | L12600 | LYNX II Automated Tissue Processor for Histology and Microscopy. |

| Digital camera software | Gatan | L12600 | Digital Micrograph |

| Spurr's resin | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 14300 | Embedding resin. It provides excellent penetration for embedding tissues and rapid infiltration. The blocks have excellent trimming and sectioning qualities, while thin sections reveal tough qualities under the electron beam. |

| Ethyl Alcohol | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 15058 | 100% Ethyl alcohol with molecular sieve, 50% and 70%. |

| Glutaraldehyde, 25% EM Grade Aqueous in Serum Vial | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 16214 | 2.5% gluteraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2-7.4 made from 25% gluteraldehyde, primary fixative for TEM tissue specimens. |

| Osmium tetroxide | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 19110 | Second fixative during TEM tissue processing used as OsO4 in distilled water |

| Polyethylene capsules | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 70021 | Flat Bottom Embedding Capsules, Size 00 |

| Scintillator | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 82010 | Phillip Quad Detector |

| Single Edge Razor Blade | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 71952-10 | Blade for Clean Rm., 10/Disp. . |

| Sodium Cacodylate Buffer | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 11655 | Sodium Cacodylate Buffer, 0.4M, pH 7.2, prepared from Sodium Cacodylate Trihydrate |

| Tannic Acid, Reagent, A.C.S., EM Grade | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 21700 | Reagent as established by the American Chemical Society (ACS Reagent). |

| Transmission Electron Microscope (1) | Hitachi | Hitachi 7100 | We use it at the HV 75 setting |

| Transmission Electron Microscope (2) | JEOL | JEM-1010 | We use it at the HV 38 setting |

| Toluene | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 22030 | Reagent as established by the American Chemical Society (ACS Reagent) |

| Ultracut microtome | Leica | 11865766 | Ultramicrotome |

| Uranyl acetate | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 22400 | Uranyless, substitute for uranyl acetate |

References

- Nitta, R., Imasaki, T., Nitta, E. Recent progress in structural biology: lessons from our research history. Microscopy (Oxford). 67 (4), 187-195 (2018).

- Moser, T. H., et al. The role of electron irradiation history in liquid cell transmission electron microscopy. Science Advances. 4 (4), (2018).

- Gordon, R. E. Electron microscopy: A brief history and review of current clinical application. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1180, 119-135 (2014).

- Sergi, C. M. Pathology of Childhood and Adolescence. An Illustrated Guide. 1st edn. , Springer. Berlin, Heidelberg. (2020).

- Sergi, C., Dhiman, A., Gray, J. A. Fine needle aspiration cytology for neck masses in childhood. An illustrative approach. Diagnostics (Basel). 8 (2), 28(2018).

- Sergi, C., Kulkarni, K., Stobart, K., Lees, G., Noga, M. Clear cell variant of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma: report of an unusual retroperitoneal tumor--case report and literature review). European Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 22 (4), 324-328 (2012).

- Hagenbuchner, J., et al. Nuclear FOXO3 predicts adverse clinical outcome and promotes tumor angiogenesis in neuroblastoma. Oncotarget. 7 (47), 77591-77606 (2016).

- Xu, X., Sergi, C. Pediatric adrenal cortical carcinomas: Histopathological criteria and clinical trials. A systematic review. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 50, 37-44 (2016).

- Khan, A., Feulefack, J., Sergi, C. M. Pre-conceptional and prenatal exposure to pesticides and pediatric neuroblastoma. A meta-analysis of nine studies. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 90, 103790(2022).

- Sergi, C. M. Implementing epic beaker laboratory information system for diagnostics in anatomic pathology. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 15, 323-330 (2022).

- D'Cruze, L., et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in the analysis of the spectrum of small round cell tumours at a tertiary care centre. Journal of Clinical Diagnostic Research. 7 (7), 1377-1382 (2013).

- Garcia, E., et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, regulated by beta-catenin and Twist, leads to esophageal wall remodeling in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. PLoS One. 17 (3), 0264622(2022).

- Al-Bahrani, R., Nagamori, S., Leng, R., Petryk, A., Sergi, C. Differential expression of sonic hedgehog protein in human hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Pathol and Oncology Research. 21 (4), 901-908 (2015).

- Taweevisit, M., Thorner, P. S. Electron microscopy can still have a role in the diagnosis of selected inborn errors of metabolism. Pediatric and Developmental Pathology. 22 (1), 22-29 (2019).

- Ghadially, F. N. Diagnostic Electron Microscopy of Tumours. , Butterworths. (1980).

- Geiger, K., et al. FOXO3/FKHRL1 is activated by 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine and induces silenced caspase-8 in neuroblastoma. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 23 (11), 2226-2234 (2012).

- Shimada, H. Transmission and scanning electron microscopic studies on the tumors of neuroblastoma group. Acta Pathologica Japonica. 32 (3), 415-426 (1982).

- Samardzija, G., et al. Aggressive human neuroblastomas show a massive increase in the numbers of autophagic vacuoles and damaged mitochondria. Ultrastructural Pathology. 40 (5), 240-248 (2016).

- Suganuma, R., et al. Peripheral neuroblastic tumors with genotype-phenotype discordance: a report from the Children's Oncology Group and the International Neuroblastoma Pathology Committee. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 60 (3), 363-370 (2013).

- Joshi, V. V. Peripheral neuroblastic tumors: pathologic classification based on recommendations of international neuroblastoma pathology committee (Modification of shimada classification). Pediatric and Developmental Pathology. 3 (2), 184-199 (2000).

- Schultz, T. D., Sergi, C., Grundy, P., Metcalfe, P. D. Papillary renal cell carcinoma: report of a rare entity in childhood with review of the clinical management. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 46 (6), 31-34 (2011).

- Brisigotti, M., Cozzutto, C., Fabbretti, G., Sergi, C., Callea, F. Metanephric adenoma. Histology and Histopathology. 7 (4), 689-692 (1992).

- McKillop, S. J., et al. Adenovirus necrotizing hepatitis complicating atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor. Pediatric International. 57 (5), 974-977 (2015).

- Kim, N. R., Ha, S. Y., Cho, H. Y. Utility of transmission electron microscopy in small round cell tumors. Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine. 49 (2), 93-101 (2015).

- Iida, M., Tsujimoto, S., Nakayama, H., Yagishita, S. Ultrastructural study of neuronal and related tumors in the ventricles. Brain Tumor Pathology. 25 (1), 19-23 (2008).

- Erlandson, R. A., Nesland, J. M. Tumors of the endocrine/neuroendocrine system: an overview. Ultrastructural Pathology. 18 (1-2), 149-170 (1994).

- Sergi, C. Microscopy Science: Last Approaches on Educational Programs and Applied Research.Microscopy. Torres-Hergueta, E., Méndez-Vilas, A. , Formatex Research Center S.L. 101-112 (2018).

- Song, D., et al. FOXO3 promoted mitophagy via nuclear retention induced by manganese chloride in SH-SY5Y cells. Metallomics. 9 (9), 1251-1259 (2017).

- Chiu, B., Jantuan, E., Shen, F., Chiu, B., Sergi, C. Autophagy-inflammasome interplay in heart failure: A systematic review on basics, pathways, and therapeutic perspectives. Annals of Clinical and Laboratory Science. 47 (3), 243-252 (2017).

- Radogna, F., et al. Cell type-dependent ROS and mitophagy response leads to apoptosis or necroptosis in neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 35 (29), 3839-3853 (2016).

- Franchi, A., et al. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural investigation of neural differentiation in Ewing sarcoma/PNET of bone and soft tissues. Ultrastructural Pathology. 25 (3), 219-225 (2001).

- Llombart-Bosch, A., et al. Soft tissue Ewing sarcoma--peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor with atypical clear cell pattern shows a new type of EWS-FEV fusion transcript. Diagnostic Molecular Pathology. 9 (3), 137-144 (2000).

- Parham, D. M., et al. Neuroectodermal differentiation in Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors does not predict tumor behavior. Human Pathology. 30 (8), 911-918 (1999).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved