Evaluating the Accuracy of Snap Judgments

Genel Bakış

Source: Diego Reinero & Jay Van Bavel—New York University

Social psychologists have long been interested in the way people form impressions of others. Much of this work has focused on the errors people make in judging others, such as the exaggerated influence of central traits (such as "warm" and "cold"), the insufficient weight given to the context in which others' behavior takes place, and the tendency for people to make judgments that conform to their initial expectations about another. However, this focus on errors masks the fact that people are quite good at making fairly accurate judgments about other people's characteristics, an ability that was no doubt important over the course of human evolution.

Indeed, the human ability to make quick sense of social situations and people ranks among our most valuable skills. What is particularly impressive about our ability to make sense of others is not just how little information we need to make inferences, but how well calibrated we can be with so little information. This video shows some experimental techniques used by psychology researchers, including Ambady and Rosenthal in their seminal work,1 and explores the process of making inferences in the context of students' evaluations of their teachers.

İlkeler

In much of the early research, the judgments were based on exposures to both verbal and nonverbal channels of the targets' behavior. However, later research suggested that strangers' judgments might be related to the presence of observable cues, particularly nonverbal behavior and physical appearance cues. Thus, new experiments were designed (like the present) to examine the mediating effect of nonverbal behavior and physical appearance on the accuracy of personality judgments. In these experiments, researchers controlled the information available to raters so that targets were rated solely on the basis of their nonverbal behavior, and they also obtained separate judgments of the physical attractiveness of targets to examine the relationship between physical appearance and the accuracy of personality judgments.

Another factor in determining the accuracy of snap judgments is the degree of correspondence between a judgment and a criterion. Early research used self-reported criterion; however, this data is susceptible to bias. Later studies, like the current techniques, avoid self-reports in favor of pragmatic and ecological valid criterion involving 3rd party reports (here, student evaluations).

A final principle involves the fact that in examining the accuracy of strangers' judgments regarding personality attributes of the targets from very minimal noninteractive information, researchers consider both molecular and molar nonverbal behavior. Psychologists define molecular behavior as behavior described in small response units (momentary, discrete responses) rather than larger ones. Molar behavior, on the other hand, is described in large response units that take up varying amounts of time.

Prosedür

1. Organize materials.

- Create videos, which includes previously filmed footage of 10 college instructors. The content of the teaching should cover a broad array of subject areas.

- For each teacher, identify three separate, 10-s clips. The three clips should be taken from the beginning, middle, and end of class, respectively, and feature the teacher alone in the video frame.

- Following Latin-square designs, combine the three clips in random order; do this for each teacher. This will result in 30 total video clips.

- Compile the end-of-semester student evaluations for each of the 10 instructors in the videos. These evaluations are from the actual courses that correspond to the video footage.

2. Participant Recruitment

- Conduct a power analysis and recruit a sufficient number of participants to watch and rate the video clips.

- Women were preferred in the original study because prior research supports the notion that they are better than men at decoding nonverbal behavior.

3. Data Collection

- Tell participants to provide ratings of the instructor based on overall nonverbal behavior. In particular, ask participants to judge the teacher on 15 teaching-related dimensions (e.g., accepting, active, attentive, dominant, honest, likable, warm, professional, etc.) on a 9-point Likert scale (1= not at all; 9 = very).

- Participants should receive no other training.

- To assess molecular nonverbal behavior (i.e., specific nonverbal actions), have two paid, trained coders watch the same video clips.

- For each clip, tally the number of nods, headshakes, smiles, laughs, yawns, frowns, biting of the lips, downward gazes, self-touches, fidgets, emphatic gestures, and weak gestures the teachers made.

- Have the two raters also indicate the teacher's symmetry and body posture.

- To account for attractiveness effects, also have two coders judge the physical attractiveness of each teacher based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all; 5 = very) based on a single photo of each teacher taken from the video.

- Fully debrief participants.

4. Data Analysis

- Note that the primary outcome variable of interest is teaching effectiveness, which is assessed via ratings made by the teachers' students at the end of the semester.

- This includes two items that asked the students to rate the instructor's performance and the quality of the course overall.

- Convert these ratings to percentages.

- The mean percentage of the two evaluation items serves as the primary dependent variable of interest.

- Analyze the ratings of molar nonverbal behavior for reliability.

- From these data, compute an overall mean, which represents the molar nonverbal behavior composite score.

- Both the composite score and each of the individual 15 ratings are considered as potential predictors of teaching effectiveness.

- Analyze coders' ratings of molecular nonverbal behaviors for reliability.

- Analyze ratings of teachers' attractiveness for reliability.

Sonuçlar

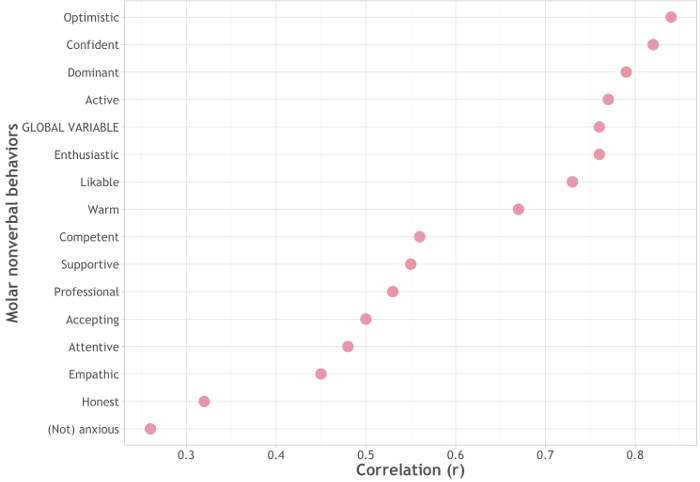

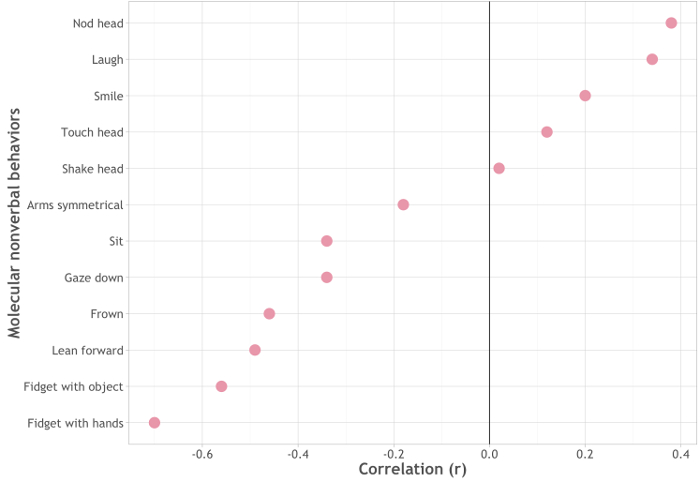

Results indicated that nine of the 15 molar ratings of nonverbal behavior positively correlated with end-of-semester ratings of teacher effectiveness (Figure 1), as did the overall mean molar rating. Molecular behaviors, on the other hand, were less predictive (Figure 2); only frowning and fidgeting (negatively) correlated with teaching effectiveness (Figure 3). Teacher attractiveness did not significantly relate to teacher effectiveness. More importantly, the effects of nonverbal behavior remained even after statistically controlling for attractiveness. Thus, when given only 30 s of film from one day of instruction, assessments of nonverbal behaviors correlated very highly with students' impressions of their teachers based on a semester's worth of contact.

Figure 1: Correlations of molar nonverbal behaviors and students' ratings of teacher effectiveness. Molar nonverbal behaviors (i.e., trait judgments) from the thin-slice video clips were correlated with students' end-of-semester ratings of teacher effectiveness. Ten of the 15 molar nonverbal behaviors predicted ratings of teacher effectiveness (optimistic, confident, dominant, active, enthusiastic, global variable, likable, warm, competent, supportive).

Figure 2: Correlations of molecular nonverbal behaviors and molar global rating. Molecular nonverbal behaviors (i.e., specific nonverbal actions) from the thin-slice video clips were correlated with the teachers' overall molar global rating. Only frowning was negatively correlated.

Figure 3: Correlations of molecular nonverbal behaviors and students' ratings of teacher effectiveness. Molecular nonverbal behaviors (i.e., specific nonverbal actions) from the thin-slice video clips were correlated with students' end-of-semester ratings of teacher effectiveness. Fidgeting was negatively correlated with the criterion variable: Teachers who fidgeted more with their hands or fiddled with an object, such as chalk or a pen, received significantly lower ratings from their students.

Başvuru ve Özet

The described technique demonstrates that observing just 30 s of behavior is enough to draw accurate inferences about teaching effectiveness. Ambady and Rosenthal repeated this study using even shorter clips and found similar effects: Judgments based on three clips as short as 2.0 s yield high correlations with end-of-semester ratings.1 Knowledge of the nonverbal correlates of effective teaching help our understanding of the importance of affective behavior in teaching and learning processes, and are also of practical importance in guiding the selection and training of future teachers.

This body of research has been extended beyond judgments of teaching effectiveness. Research has shown that people can judge how trustworthy an individual is just from viewing a photo of that person for a few brief seconds. Others have found that people can predict who will win an election with above-chance accuracy just based on viewing photos of the candidates. The ability to quickly infer another person's character or traits from a brief exposure is referred to as thin slicing.

People can thin slice others with an impressive degree of accuracy. However, this accuracy depends in large part on knowing which factors are important. For example, research conducted by relationship expert John Gottman and colleagues shows that divorce can be predicted at higher-than-chance levels by viewing a thin slice of video of a couple interacting.2 Gottman identified four key behaviors that predict divorce: criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and withdrawing/stonewalling. Interestingly, complaining and anger actually do not predict divorce.

In addition, many professions rely on accurate thin-slicing, ranging from detective work and personal security to poker playing and psychic reading. It may be that implicitly or explicitly learning to attune to the right signals is crucial to developing this expertise.

Referanslar

- Ambady, N. & Rosenthal, R. (1993). Half a minute: Predicting teacher evaluations from thin slices of nonverbal behavior and physical attractiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 431-441.

- Gottman, J. M., Coan, J., Carrere, S., & Swanson, C. (1998). Predicting marital happiness and stability from newlywed interactions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 60, 5-22.

Atla...

Bu koleksiyondaki videolar:

Now Playing

Evaluating the Accuracy of Snap Judgments

Social Psychology

21.0K Görüntüleme Sayısı

Creating the Minimal Group Paradigm

Social Psychology

25.5K Görüntüleme Sayısı

Evaluating the Accuracy of Snap Judgments

Social Psychology

21.0K Görüntüleme Sayısı

Büyük Yetişkinlerin Bilişsel Testleri Sırasında Negatif Yaşlanma Stereotiplerinin Etkisini Vurgulama ve Azaltma

Social Psychology

7.2K Görüntüleme Sayısı

JoVE Hakkında

Telif Hakkı © 2020 MyJove Corporation. Tüm hakları saklıdır