Inattentional Blindness

Przegląd

Source: Laboratory of Jonathan Flombaum—Johns Hopkins University

We generally think that we see things pretty well if they are close by and right in front of us. But do we? We know that visual attention is a property of the human brain that controls what parts of the visual world we process, and how effectively. Limited attention means that we can't process everything at once, it turns out, even things that might be right in front of us.

In the 1960s, the renowned cognitive psychologist Ulrich Neisser began to demonstrate experimentally that people can be blind to objects that are right in front of them, literally, if attention is otherwise distracted. In the 1980s and 1990s, Arien Mack and Irvin Rock followed up on Neisser's work, developing a simple paradigm for examining how, when, and why distracted attention can make people fail to see the whole object. Their experiments, and Neisser's, did not involve people with brain damage, disease, or anything of the sort, just regular people who failed to see objects that were right in front of them. This phenomenon has been called inattentional blindness. This video will demonstrate basic procedures for investigating inattentional blindness using the methods of Mack and Rock.1

Procedura

1. Stimuli and design

- The stimuli for this experiment can be made with basic slide software such as PowerPoint or Keynote.

- The first stimulus to make is called the noncritical stimulus.

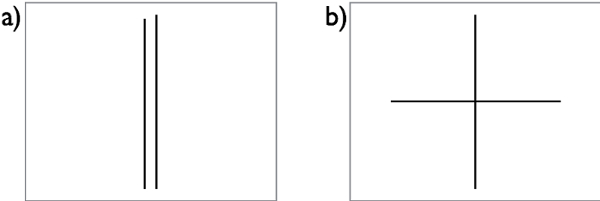

- On a white slide, create two black lines; the first should be about 80% of the vertical length of the whole slide, and the other just slightly longer. In Figure 1a, the slide is 770 px long, the shorter line is 630 px long, and the other is 645 px.

- Now choose the shorter of the two lines and rotate it by 90° so that it is horizontal, and center the two lines in the middle of the screen so that they form a cross, as in Figure 1b.

- Duplicate the slide just made, but make the shorter line the vertical arm of the cross, and the longer line the horizontal arm of the cross, as in Figure 2.

Figure 1. (a) Two lines that are used to construct the cross stimulus in (b). The line on the left is slightly shorter than the one on the right, a difference that is easy to see when they are aligned and oriented vertically, but difficult to see when they are oriented to form a cross. The cross in (b) is an example of the noncritical stimulus. The task of participants is to judge which line of the cross is longer. (In the case shown, the vertical line is longer). The difficulty of this task draws on attention.

Figure 2. An example of a noncritical stimulus. In this example, the horizontal line is the longer one. Seeing the difference should be very difficult.

- Now make the critical stimuli.

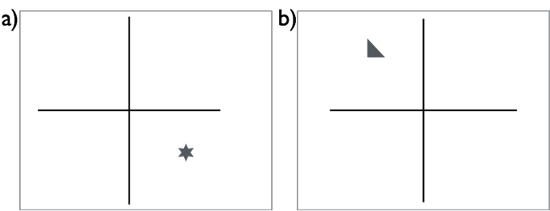

- Just duplicate the two noncritical stimuli. In the first, create a small grey star and place it in one of the four quadrants, in Figure 3a the star is in the lower-right. In the second critical stimulus, make a small grey triangle, and place it in any of the quadrants. In Figure 3b the triangle is in the upper left quadrant.

Figure 3. Two examples of critical stimuli. Each of the stimuli has a shape in one of the quadrants defined by the cross. The question of interest in the experiment will be whether observers see this shape under various conditions of attentional engagement with the task.

- Finally, make the fixation stimulus and the mask.

- The fixation stimulus is just a blank slide with a small cross in the center, 20 x 20 px.

- To make a mask, set each pixel randomly to black or white. Figure 4 shows an example.

Figure 4. A mask stimulus. In the mask, each pixel or square in the slide is set randomly to black or white. The purpose of a mask like this is to flush previous stimuli from the visual system. It allows experimenters to finely control the amount of time that an observer is exposed to a specific stimulus. This is because activity in retinal cells and brain cells can persist, even after a stimulus is absent. A blank screen-especially a dark one-lets activity persist for an especially long time, even producing afterimages. A mask, like the one shown, randomly rearranges all the firing in visually responsive neurons rather than allowing their prior activity to persist after the stimulus has been removed.

- All that remains is to assemble the images just created into trials. There are two types of trials. To make a noncritical trial, present the fixation stimulus for 1500 ms, followed immediately by one of the noncritical stimuli for 200 ms, followed immediately by the mask for 500 ms. Figure 5a schematizes the sequence.

- The critical trials are identical to the non-critical ones with one exception: Include, here, a critical stimulus for 200 ms, instead of the noncritical stimulus. Figure 5b schematizes the sequence of events.

Figure 5. Schematic depictions of the sequences of events in (a) noncritical and (b) critical trials. The only difference between the two trial types is which stimulus is shown in the middle for 200 ms, the critical or the noncritical. Each block of the experiment will include three trials, two noncritical trials followed by a critical one.

- Experimental design: The experiment will ultimately involve a total of nine trials, in three groups. The first group of three trials is called the inattention set, the second group is called the divided attention set and the third is called the complete attention set.

- Each group of trials will involve two noncritical trials followed by a critical trial. The only difference between the three groups of trials is in the instructions given to participants.

2. Running the experiment

- An experiment requires at least 50 participants, but each session is very short. The original experiments were run by recruiting participants at a science museum. A library or a campus quad on a nice day are also good places.

- To test a participant, use the following procedure:

- Ask someone if they are willing to participate in a very short experiment on visual perception.

- When they say yes, point to the computer screen, with the fixation stimulus already present, and say the following: "I'd like you to just point your eyes at this cross, without moving them. In a moment, the cross will be replaced by a larger cross, but in that one, one of the lines will be just a little longer than the other. I'd like you to carefully look at that cross, and try to report which one is longer, the horizontal or the vertical line. The cross will be present very briefly-for much less than one second-so you really need to look closely when you have the chance."

- Ask the participant if she has questions, and after answering any, run the first noncritical stimulus of the inattention set. Write down whether the participant reported the horizontal or vertical line as the longer.

- Now run the second noncritical trial, and then run the critical trial to complete the inattention set.

- After the critical trial, ask the following question, and record the participant's answer: "In that last trial, or any of the others, did you see anything else on the screen besides for the test cross?" If the participant says, 'yes', ask her to describe what they saw and where she saw it, recording the complete answer.

- Now it is time to run the divided attention trials. To begin, just say the following to the participant: 'I'd like you now to do three more trials. Are you ready?"

- Again, run two noncritical trials, followed by a critical one. After, the critical trial, ask the participant if they saw anything unexpected, what it was, and where.

- Finally, run the complete attention trials, by saying the following: "I'd like you to do three more trials. But this time, you don't need to tell me which of the two lines is longer. Instead after each trial, just tell me whether you saw anything besides for the two lines, what it was, and where on the screen it was.

- Run two noncritical trials followed by a critical one.

3. Data analysis

- To analyze the results, look at the responses given by each participant to each of the critical trials. Remember, those are the trials that have a shape somewhere in the display along with the large cross. Mark whether the participant saw the stimulus, counting it as seen if the participant reported the shape or the quadrant that it appeared in correctly.

- Sum up the number of participants who saw the stimulus in each set of trials (inattention, divided attention, and complete attention).

Wyniki

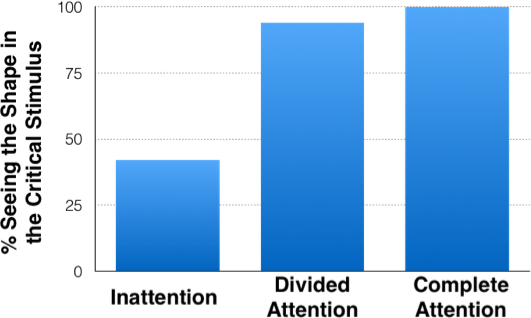

Figure 6 graphs the percent of participants who saw the critical stimulus in the critical trial of each of the three types of trial sets. Note that far fewer saw it in the inattention set, and more importantly, in that set only about 40% saw the stimulus at all. That means that 60 out of every 100 participants failed to see a large object right in front of them. This failure is what is called inattentional blindness. The length judgment task is difficult and uses up all of the observer's attention. As a result, there is no attention left to process the unexpected shape, and this demonstrates that seeing something requires attending to it.

Figure 6. Results of an inattentional blindness experiment including 50 participants. The primary dependent variable of interest is the percent of participants who accurately reported the position or shape of the critical stimulus in a critical trial. There was one critical trial in each set of three trials, and there were three sets: the inattention set, the divided attention set, and the complete attention set. More than half of participants failed to see the shape in the inattention critical trial, a result that demonstrates the presence of inattentional blindness.

In contrast, in the divided attention and complete attention trials the observer has already been asked about unexpected objects, or even told to look for them. As a result, the observer allocates some attention throughout the display, and this allows her to process and see the shapes presented in the third (critical) trial of each set. As the figure shows, all or nearly all participants should see the shape in the divided and complete attention critical trials.

Note that the divided attention trials receive their name because of the fact that once the observer has been asked about unexpected objects, those objects stop being entirely unexpected. It is therefore assumed that the observer will allow some attention to search the displays on those trials. The complete attention trials are named accordingly because the instructions in those trials direct the observer to focus entirely on seeing any object besides for the cross.

Wniosek i Podsumowanie

An important set of applications for inattentional blindness research is in the domain of driving safety. When people have car accidents, it is not uncommon for them to report that they failed to see the car, or person, or object that they hit. It makes sense to think they failed to see it because they were perhaps looking away. Inattentional blindness suggests that they could fail to see even while looking in the right place, that is, if attention is distracted. Researchers have used driving simulators, therefore, to conduct experiments on whether inattentional blindness may cause car accidents and how to reduce accidents. For example, talking on a cell phone appears to engage attention and increase the likelihood of an accident induced by inattentional blindness.

Odniesienia

- Rock, I., Linnet, C. M., Grant, P.I., and Mack, A. (1992). Perception without Attention: Results of a new method. Cognitive Psychology 24 (4): 502-534.

Tagi

Przejdź do...

Filmy z tej kolekcji:

Now Playing

Inattentional Blindness

Sensation and Perception

13.2K Wyświetleń

Color Afterimages

Sensation and Perception

11.1K Wyświetleń

Finding Your Blind Spot and Perceptual Filling-in

Sensation and Perception

17.3K Wyświetleń

Perspectives on Sensation and Perception

Sensation and Perception

11.8K Wyświetleń

Motion-induced Blindness

Sensation and Perception

6.9K Wyświetleń

The Rubber Hand Illusion

Sensation and Perception

18.3K Wyświetleń

The Ames Room

Sensation and Perception

17.4K Wyświetleń

Spatial Cueing

Sensation and Perception

14.9K Wyświetleń

The Attentional Blink

Sensation and Perception

15.8K Wyświetleń

Crowding

Sensation and Perception

5.7K Wyświetleń

The Inverted-face Effect

Sensation and Perception

15.5K Wyświetleń

The McGurk Effect

Sensation and Perception

16.0K Wyświetleń

Just-noticeable Differences

Sensation and Perception

15.3K Wyświetleń

The Staircase Procedure for Finding a Perceptual Threshold

Sensation and Perception

24.3K Wyświetleń

Object Substitution Masking

Sensation and Perception

6.4K Wyświetleń

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone