Method Article

Laparoscopic Splenectomy with Pericardial Devascularization for Hypersplenism and Esophageal Variceal Hemorrhage Due to Portal Hypertension

* Ces auteurs ont contribué à parts égales

Dans cet article

Résumé

With the rapid advancement of laparoscopic techniques, the minimally invasive benefits of laparoscopic splenectomy combined with pericardial devascularization have become increasingly evident. In this context, we present a protocol for performing laparoscopic splenectomy alongside pericardial devascularization to treat hypersplenism and esophageal variceal hemorrhage resulting from portal hypertension.

Résumé

Hypersplenism and esophageal variceal hemorrhage caused by portal hypertension are common and serious complications of decompensated cirrhosis. In recent years, with the widespread application of various therapeutic methods such as drugs, endoscopy, splenic artery embolization, transjugular intrahepatic portal shunt, and liver transplantation, the role of surgery in the treatment of portal hypertension has gradually diminished, and the indications for surgical treatment have become more strictly defined. However, according to the clinical practice in China, surgical treatment of portal hypertension still holds an important role that other treatments cannot fully replace. In fact, surgical treatment of portal hypertension is widely performed in hospitals at all levels in China, saving numerous lives. Splenectomy combined with pericardial devascularization (SPD) is the most common surgical method for treating hypersplenism and esophageal variceal hemorrhage caused by portal hypertension. Long-term clinical practice has proven that SPD is a safe and effective treatment for hypersplenism and esophageal variceal rupture and hemorrhage due to portal hypertension. With the rapid development of laparoscopic techniques, the minimally invasive advantages of laparoscopic splenectomy combined with pericardial devascularization (LSPD) have become increasingly evident. However, the successful performance of LSPD mainly depends on the skill and proficiency of the surgeon. In this context, this article presents detailed techniques for LSPD.

Introduction

China has a high number of hepatitis cases, and hepatitis patients often develop cirrhosis1. Portal hypertension is a common complication of liver cirrhosis2,3. The common clinical manifestations include splenomegaly, hypersplenism, peritoneal effusion, portal-systemic collateral circulation, and portal hypertensive gastroenteropathy3,4,5. The rupture and hemorrhage of esophageal and gastric varices is the most critical complication and the leading cause of death in decompensated cirrhosis6,7,8.

In recent years, with the widespread use of various therapeutic methods such as drugs, endoscopy, splenic artery embolization, transjugular intrahepatic portal shunt, and liver transplantation, the role of surgery in treating portal hypertension has gradually diminished, and the indications for surgical treatment have been more strictly limited6,9,10,11,12,13. However, the long-standing use of surgical treatment for portal hypertension, particularly splenectomy combined with pericardial devascularization (SPD), has saved numerous lives and continues to play an indispensable role in China14,15. Long-term surgical practice has shown that SPD is safe and effective, with a low incidence of rebleeding and hepatic encephalopathy6,9,14,15,16.

With the popularization of minimally invasive surgery and advancements in laparoscopic techniques, laparoscopic splenectomy combined with pericardial devascularization (LSPD) has already been applied in clinical practice17,18,19,20,21. However, LSPD places higher demands on the technical proficiency of the surgeon. Given this, the present article provides detailed techniques for LSPD in treating hypersplenism and esophageal variceal hemorrhage caused by portal hypertension.

Protocole

A total of 8 patients who underwent LSPD between October 2012 and September 2022 were included in this study. The operations were approved by the institutional review board of The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University. All patients provided written informed consent. The consumables and equipment required for the study are listed in the Table of Materials.

1. Inclusion criteria

- Include patients with splenomegaly (The spleen is over 12 cm in any diameter) and hypersplenism (Platelet count less than 75 × 109/L) caused by portal hypertension.

- Include patients with a history of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and poor response to conservative treatment.

- Include patients with liver function of Child-Pugh grade A or B6.

2. Exclusion criteria

- Exclude patients with liver function of Child-Pugh grade C6, or with hepatic encephalopathy, severe jaundice, severe coagulation dysfunction, and massive ascites.

- Exclude patients with extensive thrombus of the main portal vein, splenic vein, and superior mesenteric vein.

- Exclude patients with heart, lung, kidney, and other vital organ dysfunction.

- Exclude patients who could not tolerate general anesthesia or pneumoperitoneum.

3. Preoperative preparation

- Perform preoperative blood tests, including liver and renal function tests, a complete blood count, coagulation function test, blood grouping, and crossmatching.

- Perform electrocardiogram, chest X-ray, cardiovascular and hepatobiliary color Doppler ultrasound, and computed tomography (CT) of the upper abdomen before surgery.

4. Surgical technique

- Position of the patient and surgeons

- Following tracheal intubation and general anesthesia (conducted according to institutionally approved protocols), position the patient supine with their legs spread 45° to 60°. Perform routine disinfection using povidone-iodine solution.

- Ensure that the surgeon is positioned on the right side of the patient, the assistant is on the left side, and the endoscope holder is placed between the patient's legs. The position of the surgeons can be adjusted according to personal habits.

- Pneumoperitoneum establishment and trocar arrangement

- Make a longitudinal incision of 10 mm below the umbilicus, inject carbon dioxide gas through a pneumoperitoneum needle, and maintain an abdominal pressure of 12 mmHg (Figure 1).

- Insert a 10 mm trocar and the laparoscope below the umbilicus. Under the direct visualization provided by the laparoscope, place a 12 mm trocar in the left and right middle abdomen, respectively. Subsequently, position a 5 mm trocar in the left and right upper abdomen, respectively (Figure 1).

- Splenic artery ligation

- Incise the gastrocolic and gastrosplenic ligaments using an ultrasonic-harmonic scalpel (Figure 2A,B). Ligate and sever the left gastroepiploic and short gastric vessels to expose the lesser omental sac and pancreas (Figure 2C).

- Incise the posterior peritoneum at the superior margin of the pancreas. Dissect and ligate the splenic artery (Figure 2D).

NOTE: After splenic artery ligation, the surface color of the spleen becomes ischemic change, which is helpful in reducing the bleeding during splenectomy.

- Splenectomy

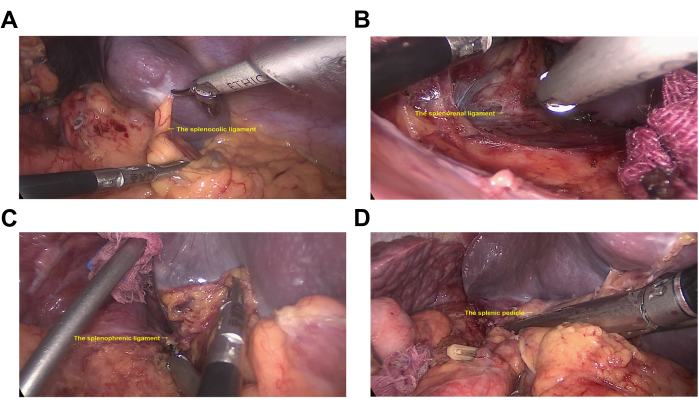

- Starting from the lower pole of the spleen, sever the splenocolic ligament (Figure 3A). Lift the lower pole of the spleen ventrally and sever the splenorenal ligament (Figure 3B).

- Close to the splenic pedicle, separate the tail of the pancreas from the splenic pedicle. Close to the upper pole of the spleen, sever the splenophrenic ligament (Figure 3C).

NOTE: At this point, the spleen is completely free. - Sever the splenic pedicle using a linear stapling device with a cartridge (height 2.6 mm, length 60 mm) (Figure 3D).

NOTE: When severing the splenic pedicle, pay attention to avoid damage to the pancreatic tail and prevent pancreatic leakage after surgery.

- Pericardial devascularization

NOTE: Devascularization for the left gastroepiploic and short gastric vessels have been done in the previous steps (Figure 2A,B).- Lift and pull the stomach toward the cephalic side. Dissect and expose the left gastric vessels in the back of the stomach. Ligate and sever the left gastric vessels (Figure 4A).

- Dissociate the posterior wall of the stomach toward the cardia. Ligate and sever the posterior gastric vessels (Figure 4B).

- Pull the stomach toward the lower left. Incise the lesser omentum and anterior serosa of the cardia.

- Dissect and expose the branches of the gastric coronary vein entering the gastric wall. Ligate and sever the gastric branches of the coronary vein (Figure 4C).

- Incise the subphrenic anterior esophageal serosa. Dissect and dissociate the lower esophagus with a length not less than 6 cm. Ligate and sever the inferior phrenic vessels and the esophageal branches of the coronary vein (Figure 4D,E).

NOTE: Pay attention to the possible presence of abnormally upper esophageal branches of the coronary vein; if present, ligation and incision are required (Figure 4F).

- Specimen removal and surgery completion

- Carefully check for remaining varicose vessels around the cardia (Figure 5A). Load the resected spleen into a specimen bag (Figure 5B).

- Flush the surgical field using sterile saline (Figure 5C). Carefully examine for active bleeding, pancreatic and gastrointestinal collateral injury. Place a drainage tube under the left diaphragm (Figure 5D).

- Remove the trocars and extend the umbilical incision to approximately 3 cm in length. Crush the spleen within the specimen bag and remove it. Complete the surgery by suturing the abdominal wall incisions.

5. Postoperative procedures

- Continuously monitor heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and temperature.

- Administer intravenous antibiotics, somatostatin, and hepatoprotective drugs after the surgery.

- Regularly check the incision site for signs of infection, such as redness, swelling, or discharge.

- If no pancreatic leakage occurs, remove the abdominal drainage tube in 5-7 days after surgery.

- Check the platelet count regularly. Anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy is prescribed if the platelet count is too high or if venous thrombosis is present.

Résultats

A total of 8 patients (mean age: 50.75 years ± 6.43 years), including 6 males (75.0%) and 2 females (25.0%), were included. The cause of portal hypertension in all eight patients with cirrhosis was viral hepatitis. There were 5 patients (62.5%) with liver function classified as Child-Pugh grade A and 3 patients (37.5%) with Child-Pugh grade B. The mean major axis of the spleen for the patients was 196.50 mm ± 12.39 mm. The mean counts of white blood cells, hemoglobin, and platelets were (3.33 ± 0.81) × 109/L, 79.38 ± 10.85 g/L, and (48.13 ± 10.37) × 109/L, respectively (Table 1).

All the patients successfully underwent LSPD without conversion to open surgery. The mean operation time was 215.63 min ± 50.19 min, with a mean intraoperative blood loss of 128.75 mL ± 44.22 mL. The mean postoperative drainage time was 5.50 ± 0.76 days, and the mean postoperative hospital stay was 6.50 ± 0.76 days. The postoperative complication rate was 25.0%, including 1 case of pulmonary infection and 1 case of ascites (Table 2).

Figure 1: The trocar arrangement. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Splenic artery ligation. (A) The left gastroepiploic vessels. (B) The short gastric vessels. (C) The pancreas and the splenic artery. (D) The splenic artery. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Splenectomy. (A) The splenocolic ligament. (B) The splenorenal ligament. (C) The splenophrenic ligament. (D) The splenic pedicle. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: Pericardial devascularization. (A) The left gastric vessels. (B) The posterior gastric vessels. (C) The gastric branch of the coronary vein. (D) The inferior phrenic vessels. (E) esophageal branch of the coronary vein. (F) The esophageal branch of the coronary vein. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5: Specimen removal and surgery completion. (A) Careful examination for remaining varicose vessels around the cardia. (B) The resected spleen is loaded into a specimen bag. (C) The surgical field is flushed using sterile saline. (D) A drainage tube is placed under the left diaphragm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| Sex (n) | |

| Male | 6 (75.0%) |

| Female | 2 (25.0%) |

| Age (years) | 50.75 ± 6.43 |

| Etiology (n) | |

| Viral hepatitis | 8 (100.0%) |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 0 (0.0%) |

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | 0 (0.0%) |

| Cholestasis | 0 (0.0%) |

| Drug or toxin | 0 (0.0%) |

| Child-Pugh grade (n) | |

| A | 5 (62.5%) |

| B | 3 (37.5%) |

| Major axis of spleen (mm) | 196.50 ± 12.39 |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 3.33 ± 0.81 |

| HGB (g/L) | 79.38 ± 10.85 |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 48.13 ± 10.37 |

Table 1: Clinical features of the patients. WBC = white blood cell; HGB = hemoglobin; PLT = platelet.

| Operation time (minutes) | 215.63 ± 50.19 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 128.75 ± 44.22 |

| Postoperative drainage time (days) | 5.50 ± 0.76 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (days) | 6.50 ± 0.76 |

| Postoperative complications (n) | 2 (25.0%) |

| Incision infection | 0 (0.0%) |

| Pulmonary infection | 1 (12.5%) |

| Abdominal infection | 0 (0.0%) |

| Postoperative bleeding | 0 (0.0%) |

| Ascites | 1 (12.5%) |

| Pancreatic leakage | 0 (0.0%) |

| Portal thrombosis | 0 (0.0%) |

Table 2: Surgical outcomes of the patients.

Discussion

A large proportion of people in China suffer from chronic hepatitis, which is an important factor leading to liver cirrhosis1,2. Patients with advanced liver cirrhosis often experience portal hypertension, resulting in a series of complications, such as splenomegaly, hypersplenism, peritoneal effusion, portal-systemic collateral circulation, and portal hypertensive gastroenteropathy3,4,5. Among these, the rupture and hemorrhage of esophageal and gastric varices is the most critical complication and the leading cause of death in decompensated cirrhosis6,7,8. According to previous literature reports, the mortality rate for the first bleeding episode is about 20%12,22. Additionally, the rate of variceal rebleeding is nearly 60%, with a mortality rate of 30%23.

In recent years, various therapeutic methods such as drugs, endoscopy, splenic artery embolization, transjugular intrahepatic portal shunt, and liver transplantation have been increasingly used in the treatment of portal hypertension6,9,10,11,12,13. Due to the unbalanced development of medical institutions at all levels in China, splenectomy combined with pericardial devascularization (SPD) still plays an indispensable role in treating hypersplenism and esophageal variceal hemorrhage caused by portal hypertension14,15. Hassab first proposed SPD for the treatment of portal hypertension in 196624. SPD relieves the excessive destruction of blood cells by removing the hyperfunctional spleen and corrects clinical manifestations such as thrombocytopenia, anemia, and granulocytopenia. Meanwhile, SPD can control bleeding by blocking abnormal blood flow between the portal vein and the azygos vein. After more than half a century of clinical practice, SPD has proven to have advantages such as high safety, a definitive hemostatic effect, low risk of rebleeding, and a low incidence of hepatic encephalopathy6,9,14,15,16.

Traditional open surgery involves larger trauma, greater intraoperative blood loss, longer postoperative recovery times, and a higher likelihood of complications such as ascites and portal vein thrombosis, which no longer meet the demand for minimally invasive procedures and fast recovery. The first laparoscopic splenectomy was reported in 1991 by Delaitre et al.25. However, there are only a limited number of studies on laparoscopic splenectomy combined with pericardial devascularization (LSPD) for the treatment of portal hypertension 17,18,19,20,21. LSPD places higher demands on the technical proficiency of the surgeon, which presents certain limitations to the development of this technique. In light of this situation, the present article provides detailed techniques for LSPD in treating hypersplenism and esophageal variceal hemorrhage caused by portal hypertension.

In the present cases, we included patients with splenomegaly and hypersplenism caused by portal hypertension. All the patients had a history of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and a poor response to conservative treatment. Preventive surgery remains controversial; it is generally not recommended for patients with no history of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The relevant disputes need to be resolved through further prospective studies to provide more evidence.

There are several surgical approaches for splenectomy; we recommend ligation of the splenic artery as a priority. The position of the splenic artery is relatively fixed, making it easy to dissect and ligate the artery at the upper margin of the pancreas without excessive tissue separation that could result in bleeding. After ligating the main splenic artery, the spleen shrinks, increasing the operating space, which facilitates lifting the spleen. Additionally, prioritizing treatment of the main splenic artery can help avoid variceal vein rupture and hemorrhage that may affect the surgical field during the dissection of secondary splenic pedicle vessels, significantly reducing the incidence of conversion and ensuring the safety of the surgery.

Care should be taken to protect the tail of the pancreas, located near the splenic pedicle, when dissecting the perisplenic ligaments to avoid pancreatic injury and reduce the risk of postoperative pancreatic leakage complications.

When dealing with variceal blood vessels, they should be separated close to the stomach wall while avoiding rough pulling that could lead to variceal vein tearing and bleeding. If massive bleeding occurs during the operation, autologous blood transfusion can be considered if conditions permit. For the lower esophagus, it is important to ensure a dissociation length of at least 6 cm to expose and ligate any abnormal upper esophageal branches of the coronary vein. The platelet count should be monitored regularly after surgery, and antiplatelet drugs should be administered judiciously based on the specific situation.

This study presents detailed techniques for laparoscopic splenectomy combined with pericardial devascularization (LSPD) for hypersplenism and esophageal variceal hemorrhage caused by portal hypertension. Based on our experience, LSPD can be preliminarily considered feasible and safe for treating portal hypertension. However, due to the small number of cases in this study, more clinical research is needed to confirm these findings. Once further clinical studies validate its safety and efficacy, LSPD is expected to be more widely used in the future. It is recommended that LSPD be performed selectively by experienced surgeons.

Déclarations de divulgation

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Remerciements

This work was supported by grants from the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou (No. 2023A04J1917), and the Medical Joint Fund of Jinan University (No. YXZY2024018).

matériels

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 10-mm trocar | Xiamen Surgaid Medical Device Co., LTD | NGCS 100-1-10 | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

| 12-mm trocar | Xiamen Surgaid Medical Device Co., LTD | NGCS 100-1-12 | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

| 5-mm trocar | Xiamen Surgaid Medical Device Co., LTD | NGCS 100-1-5 | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

| Hem-o-lok | America Teleflex Medical Technology Co., LTD | 544240 | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

| Linear stapling device | America Ethicon Medical Technology Co., LTD | PSEE60A | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

| Pneumoperitoneum needle | Xiamen Surgaid Medical Device Co., LTD | NGCS 100-1 | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

| Suction and irrigation tube | Tonglu Hengfeng Medical Device Co., LTD | HF6518.035 | Sterile,dry heat sterilized, reusable |

| Ultrasounic-harmonic scalpel | Chongqing Maikewei Medical Technology Co., LTD | QUHS36S | Sterile, ethylene oxide sterilized, disposable |

Références

- Sun, N., He, F., Sun, J., Zhu, G. Viral hepatitis in China during 2002-2021: Epidemiology and influence factors through a country-level modeling study. BMC Public Health. 24 (1), 1820 (2024).

- Jeng, W. J., Papatheodoridis, G. V., Lok, A. S. F. Hepatitis B. Lancet. 401 (10381), 1039-1052 (2023).

- Iwakiri, Y., Trebicka, J. Portal hypertension in cirrhosis: Pathophysiological mechanisms and therapy. JHEP Rep. 3 (4), 100316 (2021).

- Gracia-Sancho, J., Marrone, G., Fernández-Iglesias, A. Hepatic microcirculation and mechanisms of portal hypertension. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16 (4), 221-234 (2019).

- Simonetto, D. A., Liu, M., Kamath, P. S. Portal hypertension and related complications: Diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 94 (4), 714-726 (2019).

- Lesmana, C. R. A., Raharjo, M., Gani, R. A. Managing liver cirrhotic complications: Overview of esophageal and gastric varices. Clin Mol Hepatol. 26 (4), 444-460 (2020).

- Mokdad, A. A., et al. Liver cirrhosis mortality in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: A systematic analysis. BMC Med. 12, 145 (2014).

- Sepanlou, S. G., et al. The global, regional, and national burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 5 (3), 245-266 (2020).

- Magyar, C. T. J., et al. Surgical considerations in portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 28 (3), 555-576 (2024).

- Zheng, S., et al. Liver cirrhosis: Current status and treatment options using Western or traditional Chinese medicine. Front Pharmacol. 15, 1381476 (2024).

- Garcia-Tsao, G., Abraldes, J. G., Berzigotti, A., Bosch, J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 65 (1), 310-335 (2017).

- de Franchis, R., Baveno VI, F. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 63 (3), 743-752 (2015).

- Tripathi, D., et al. U.K. guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. Gut. 64 (11), 1680-1704 (2015).

- Yang, L. Progress and prospect of surgical treatment for portal hypertension. Chin J Pract Surg. 40 (2), 180-184 (2020).

- Zhang, C., Liu, Z. Surgical treatment of cirrhotic portal hypertension: Current status and research advances. J Clin Hepatol. 36 (2), 417-420 (2020).

- Qi, W. L., et al. Prognosis after splenectomy plus pericardial devascularization vs. transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for esophagogastric variceal bleeding. World J Gastrointest Surg. 15 (8), 1641-1651 (2023).

- Yan, C., Qiang, Z., Jin, S., Yu, H. Spleen bed laparoscopic splenectomy plus pericardial devascularization for elderly patients with portal hypertension. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 17 (2), 338-343 (2022).

- Chen, H., et al. Comparison of efficacy of laparoscopic and open splenectomy combined with selective and nonselective pericardial devascularization in portal hypertension patients. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 28 (6), 401-403 (2018).

- Hong, D., et al. Comparison of two laparoscopic splenectomy plus pericardial devascularization techniques for management of portal hypertension and hypersplenism. Surg Endosc. 29 (12), 3819-3826 (2015).

- Cai, Y., Liu, Z., Liu, X. Laparoscopic versus open splenectomy for portal hypertension: a systematic review of comparative studies. Surg Innov. 21 (4), 442-447 (2014).

- Huang, J., Xu, D. W., Li, A. Can laparoscopic splenectomy and azygoportal disconnection be safely performed in patients presenting with cirrhosis, hypersplenism and gastroesophageal variceal bleeding? How to do it, tips and tricks (with videos). Curr Probl Surg. 61 (7), 101501 (2024).

- Magaz, M., Baiges, A., Hernández-Gea, V. Precision medicine in variceal bleeding: Are we there yet. J Hepatol. 72 (4), 774-784 (2020).

- Bosch, J., García-Pagán, J. C. Prevention of variceal rebleeding. Lancet. 361 (9361), 952-954 (2003).

- Terrosu, G., et al. Laparoscopic versus open splenectomy in the management of splenomegaly: our preliminary experience. Surgery. 124 (5), 839-843 (1998).

- Delaitre, B., Maignien, B. Splenectomy by the laparoscopic approach. Report of a case. Presse Med. 20 (44), 2263 (1991).

Réimpressions et Autorisations

Demande d’autorisation pour utiliser le texte ou les figures de cet article JoVE

Demande d’autorisationThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon