Persuasion: Motivational Factors Influencing Attitude Change

Overview

Source: William Brady & Jay Van Bavel—New York University

Decades of social psychological research sought to understand a fundamental question that pervades our social life including politics, marketing and public health; namely, how are people persuaded to change their attitudes towards an idea, person, or object? Traditional work found that there are key factors that influence whether persuasion is successful or not including the source of the persuasive message ("source"), and the argument content of the message ("content"). For example, expert sources and messages with sound arguments are typically more persuasive. However, as more studies were conducted, conflicting findings began to arise in the field: some studies found that expert sources and good arguments were not always required for successful persuasion.In the 1980's, psychologists Richard Petty, John Cacioppo and their colleagues proposed a model to account for the mixed findings in studies on persuasion.1,2 They proposed the Elaboration Likelihood Model of persuasion, which stated that persuasion occurs via two routes: a central route or a peripheral route. When persuasive messages are processed via the central route, people engage in careful thinking about the messages, and therefore, the content (i.e., the quality of the argument) matters for successful persuasion. However, when messages are processed via the peripheral route, the source (e.g., an expert source) is more important for successful persuasion.

If people are motivated to pay attention to the message topic, they tend to process the message via the central route, and thus message content is more important. On the other hand, when people are not motivated to pay attention to a message topic, the message is more likely to be processed via the peripheral route and thus the source of the message is more important. Inspired by Petty, Cacioppo, and Goldman, this video demonstrates how to design a task to test different routes to successful persuasion using messages.1

Principles

To assess the success of persuasive messages under different circumstances, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) is performed on the attitudes toward a topic presented via an oral message. Three factors were predicted to affect attitude change: motivational relevance, source, and argument content. By including the variable of motivational relevance, researchers can determine if source and argument content affect successful persuasion under high- versus low-motivational relevance. This is known as testing an interaction effect.

Procedure

1. Participant Recruitment

- Conduct a power analysis and recruit a sufficient number of participants (e.g., the original study used 145) and obtain informed consent from the participants.

2. Data Collection

- Give participants the cover story for the study.

- Explain that the study is about assessing the quality of taped recordings discussing whether the university should institute an academic policy change.

- Further explain that the psychology department is cooperating with the university administration and has taped statements about the academic policy change.

- The statements should advocate a new policy where seniors would be required to take a comprehensive exam in their major area in order to graduate.

- Randomly assign participants into groups based on a 2 (high and low relevance) x 2 (strong and weak argument) x 2 (high-source and low-source expertise) factorial design.

- Participants in the high-relevance group are told that the academic policy change that is to be described in the taped message is set to be instituted next year.

- Participants in the low-relevance group are told that the policy change is set to be instituted in 10 years.

- Participants in the strong-argument group hear a taped message that includes an argument describing statistics and data (e.g., the policy led to greater standardized achievement test when implemented at other universities) supporting the policy change.

- In the weak-argument group, the argument relies on personal opinion and anecdotes (e.g., a friend of the author took the exam enforced by the policy and now has a prestigious academic position) to support the policy change.

- Participants in the high-source expertise group are told that the tape they are about to hear was prepared by the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, chaired by a professor of education at Princeton University.

- In the low-source expertise group, participants are told that the message was prepared by a class at a local high school.

- Ask participants to rate on a scale the extent to which they agree with the statement promoting the implementation of the comprehensive exam (1 = Do not agree at all to 11 = Agree completely).

- Later, standardize the responses and then average them to form one composite "agreement" measure.

- To maintain the cover story of accessing the quality of taped recordings, also ask them to rate the speaker's voice quality, the quality of their delivery, and the level of enthusiasm.

- These ratings should not be used in any statistical tests.

- Fully debrief participants.

Results

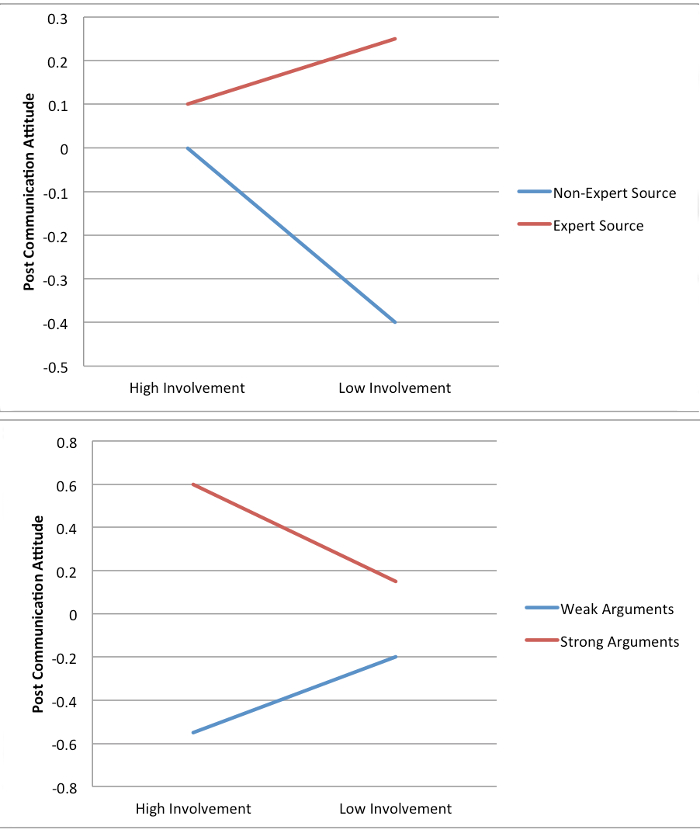

The results showed a main effect of argument quality: The strong arguments lead to greater agreement with the message than weak arguments. There was also a main effect of source: Averaged across the other conditions there was greater agreement for the message when the source had high expertise than when the source had low expertise. However, of particular interest was the discovery of an interaction effect (Figure 1). When participants were in the high-relevance group, the effect of argument quality was stronger than when the participants were in the low relevance group. The opposite was true for the source condition: when participants were in the low-relevance group, the effect of high-source expertise was greater than when the participants were in the high-relevance group.

Figure 1: The interactive effect of source expertise and motivational relevance (top) or argument quality and motivational relevance (bottom) on agreement toward the comprehensive exam message. Participants agreed with the message more if the source was an expert only when the motivational relevance was low. However, participants agreed with the message more if the argument quality was strong only when the motivational relevance was high.

Application and Summary

In the debate over what factors lead to a message being persuasive, this experiment provides a careful test of the idea that motivational factors, such as personal relevance of the message, play a pivotal role in determining the impact of factors that generally affect persuasion, including source characteristics and argument quality. The result of this experiment and the Elaboration Likelihood Model that took hold because of its results, steered the field in a new direction when it was in a battle over whether source characteristics or argument quality were the most important factors influencing persuasion. These data suggest that the answer is they are both important, but the motivational context in which the message is embedded is important to consider to determine when the factors will exert their influence on persuasion.

These results have considerable implications for areas such as marketing, politics, and public health. In terms of marketing, businesses can use the findings of the study to help design effective campaigns that are designed to spread positive messages about their product. For example, if an ad campaign on some media outlet is targeted at an audience for which the product is personally relevant (e.g., a video game targeting a demographic of teenage boys), then the research suggests that the advertisement should include factual evidence the game is a good one to buy (e.g., statistics demonstrating that everyone is playing it). If the advertisement is being presented to another audience that may buy the game but is not personally relevant for them (e.g., parents looking to a buy a game for the kid), then the source of the advertisement message is more important (e.g., the advertisement is endorsed by a pro-gamer or a computer technician).

In terms of politics, political candidates can try to persuade people about their policies differentially based on what crowd they are speaking to. When the policies they are discussing are directly relevant to their crowd, such as the case of discussing one's position on abortion to a crowd of young women, the politicians should use high quality arguments rather than rely on personal anecdotes. In other cases where the crowd is less interested in the policy being discussed, as in the case of discussing retirement policies to a young college crowd, tactics that make the candidate appear to be the expert on the issue may be more important than crafting a quality argument.

Finally, in terms of public health and other related fields, the findings of this study can be used to create effective campaigns that attempt to get the public to behave different than their currently behavior. For example, if campaigns about hypertension are targeted in low-income African American communities where hypertension rates higher than average, constructing an argument that appears to be supported by data and facts may be more important than emphasizing the source of the public-service advertisement.

References

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1984). Source Factors and the Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. Advances in Consumer Research, 11, 668-672.

- Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Goldman, R. (1981). Personal involvement as a determinant of argument-based persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 847-855.

Skip to...

Videos from this collection:

Now Playing

Persuasion: Motivational Factors Influencing Attitude Change

Social Psychology

25.6K Views

The Implicit Association Test

Social Psychology

52.2K Views

Persuasion: Motivational Factors Influencing Attitude Change

Social Psychology

25.6K Views

Misattribution of Arousal and Cognitive Dissonance

Social Psychology

16.7K Views

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved