Method Article

Surgical Closure of Equine Abdomen, Prevention, and Management of Incisional Complications

In This Article

Summary

This paper describes a method of abdominal wall closure using tension and apposition sutures in horses undergoing ventral midline laparotomies. It also describes methods for prevention and management of postoperative incisional complications, such as bandaging, negative pressure therapy, and in case of wound breakdown, the application of retention sutures.

Abstract

Although rarely fatal, complications of ventral midline laparotomy incision in equine patients increase hospitalization cost and duration and may jeopardize return to athletic function. Therefore, many techniques have been developed to reduce their occurrence and expedite their resolution when they occur. Our technique of celiotomy incision closure includes the use of tension sutures (vertical U mattress) of polyglactin 910 on the linea alba, which is then apposed by polyglactin 910 interrupted sutures or a simple continuous pattern suture with a stop midway before routine closure of the superficial layers. The celiotomy incision is protected by an elastic bandage during the immediate postoperative period. This technique has been associated with favorable results: 5.3% confirmed incisional infections after a single celiotomy and 26.7% after repeat celiotomy. The overall incisional complication (serous/sanguineous discharge, hematoma, infection, hernia formation, and complete wound breakdown) occurrence was 9.5% and 33.3% after single and repeat laparotomy, respectively. In cases considered more susceptible to infection (early relaparotomy or laparotomy incisions longer than 30 cm), negative pressure therapy was found easy to apply on closed incisions. No detrimental effects were observed. However, the potential prophylactic benefit of this therapy needs to be confirmed in a larger group. In infected laparotomy wounds requiring drainage, the use of negative pressure therapy seemed to have a positive effect on the formation of granulation tissue. However, there was no control group to allow statistical confirmation. Finally, one case of complete breakdown of the laparotomy incision was managed by stainless steel retention sutures, the application of negative pressure therapy, and a hernia belt. At re-evaluation 15 months post-surgery, several small hernias were detected, but the horse had returned to his previous level of sports performance and had not shown any episode of colic.

Introduction

The ventral midline celiotomy is the most frequent surgical approach to the abdomen in horses with acute colic1 or in need of cesarean section2. The created ventral incision may be the site of several postoperative complications, such as (sero) sanguineous discharge, infection, hernia formation, and complete wound breakdown3. Except for the case of complete wound breakdown, laparotomy incision complications are rarely fatal, but they increase hospitalization duration and costs and may prevent return to athletic function4,5.

Among incisional complications, infection should be considered one of the most clinically relevant, as its prevalence ranges from 2.7% to 40%6 and can be as high as 68.4% after early repeat laparotomy7. Furthermore, incisional infection is considered a major risk factor for subsequent hernia formation8. Therefore, for several decades, many efforts have been made to reduce the occurrence of incisional infections and expedite their resolution when they occur.

Several techniques of closure of the equine abdomen have been described5. Overall, the linea alba is most frequently closed with a simple continuous pattern, mainly because of its even distribution over the entire incision line, its fast application, and a generally good outcome5,9. However, the closure of the linea alba in an interrupted pattern has also been associated with good results3,10. The subcutaneous and cutaneous tissues may be closed by multiple patterns and with different types of material4,5,11.

In many equine hospitals, postoperative abdominal bandages are now routinely used to protect and provide some support to incision1. Several types of bandages have been described, including elastic bandages and commercially produced hernia belts12, but the actual types of bandages and timing of placement reported in the literature are sometimes unclear.

Despite all the prevention methods used, incisional infection may occur. In these cases, staples or sutures need to be removed in order to evacuate the purulent material and create a ventral drainage for large subcutaneous pockets. Frequent wound cleaning and removal of secretions are indicated to allow the wound to heal by the second intention. Abdominal bandages are particularly encouraged in infected cases for support and to decrease the risk of dehiscence or stretching of the weakened abdominal wall6.

For more than 25 years, negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has been used for the treatment of open wounds in human13 and animal patients14. Recently, negative pressure therapy has been investigated as a possible prophylactic measure to prevent complications via immediate application after surgery in high-risk, clean, closed surgical incisions and showed encouraging results15,16. The reported properties of NPWT are wound environment stabilization, wound edema/bacterial load reduction, improved tissue perfusion, as well as granulation tissue, and angiogenesis stimulation13. The management of abdominal wound dehiscence with negative pressure therapy has shown successful results in human patients with compromised healing17. In the rare cases of complete acute or delayed breakdown of the incision in horses, the abdominal wall should be closed with interrupted through-and-through stainless steel retention sutures, and the skin incision left to heal by second intention18. Encouraging results in human medicine suggest that negative pressure therapy could be used as part of the management of dehiscence cases in equine patients, as well as any infected incisional wound, which to our knowledge has not been reported yet.

The aim of this paper is to describe our technique of closure of the equine abdomen with an interrupted pattern using a combination of tension and apposition sutures on the linea alba and our postoperative protocol. This includes abdominal bandaging and, in some cases, the use of negative pressure therapy for the prevention and treatment of incisional complications. Our technique for management of delayed breakdown of the incision is also presented.

Protocol

This retrospective study is based on our clinical records. Our practice fully respects the animal care guidelines of our institution, the Equine Clinic of the University of Liège. Animals included in the study were horses and ponies (mares, intact and gelded males) of various breeds (mainly Warmbloods), of various ages (from 5 months to 34 years, with a mean age around 10 years) and of various weights (from 50 kg to 840 kg, with a mean weight around 500 kg).

1. Surgical technique (ventral midline laparotomy for colic or C-section)

- Surgical preparation and incision

- Preoperatively, administer intravenous (IV) sodium penicillin (20,000 IU/kg), gentamicin (6.6 mg/kg or 8.8 mg/kg), and flunixin meglumine (1.1 mg/kg) +/- subcutaneous enoxaparin (150 mg/500 kg of bodyweight) to the horse.

- After induction of general anesthesia, place the horse in dorsal recumbency.

NOTE: Confirm proper anesthetization by recumbency and the decrease of palpebral reflex. Administer polymer eye ointment to prevent dryness of the cornea during anesthesia. - Trim the abdominal hair and shave a 10 cm wide band centered on the linea alba. In males, wash the penis and sheath with 3.75% povidone-iodine soap or 4% chlorhexidine digluconate soap until visually clean. Then grossly clean the abdomen with 3 cycles of 3.75% povidone-iodine soap or 4% chlorhexidine soap and rinse with tap water.

- Place a urinary catheter. For males, after placement of a stack of 4 inch x 4 inch gauze pads, close the prepuce using Backhaus towel clamps.

- Prepare the abdomen aseptically with a 5 min scrub with 3.75% povidone-iodine or 4% chlorhexidine soap, and rinse after the last cycle with 70% isopropyl alcohol. Finally, spray a 3% povidone-iodine in isopropyl alcohol solution on the surgical site i.e., ventral abdomen, centered on the linea alba.

- Double drape the abdomen: place an iodophor adhesive film on the intended surgical site and drapes from a universal pack around. Then, cover them with a laparotomy drape with incise film on its center.

NOTE: For C-section, place additional drapes. These will be removed once the foal has been extracted and the uterus is closed. - Perform the ventral midline laparotomy cranial to the umbilicus, as routinely done. If required by surgical procedures, extend the (15-20 cm initial) incision further cranially and/or caudally. Perform hemostasis by the application of hemostatic forceps.

- During surgery, repeat intravenous sodium penicillin (20,000 IU/kg) every 90 min.

- Closure of the abdomen

- Change surgical gloves. Dissect the subcutaneous tissue over a width of 1-2 cm along the incision.

- Tension sutures: Preplace (but do not immediately tighten) a series of vertical U mattress sutures (6 metric polyglactin 910) 3 cm apart on the muscular layer.

- To do so, place the far-far loop approximately 1.5 cm from the linea alba incision and the near-near loop at approximately 0.5 cm from the incision. Ensure that retroperitoneal fat and peritoneum are excluded from the sutures. Keep each suture with long strands and place a hemostatic clamp on both strands of each suture.

- When all sutures are preplaced, hold them under tension by an assistant and knot each of them separately.

- Apposition sutures to obtain a tight closure of the linea alba: place interrupted sutures (usually a combination of simple, cruciate, and/or inverted cruciate sutures; 2 and/or 6 metric polyglactin 910) in between the vertical mattress sutures. At the end of this step, check the tightness of the closure with the closed tip of a needle holder: it can no longer pass through the incision.

NOTE: Alternatively, tight closure of the linea alba can be reached using a simple continuous pattern (6 metric polyglactin 910), interrupted 1 or 2 times (depending on the length of the incision) applied on the linea alba over the vertical mattress sutures. - Rinse the incision with 1 L of saline and remove all blood clots with gauze.

NOTE: The rinsing solution may contain 20 mL of 10% gentamicin, depending on the surgeon's preference. - Close the subcutaneous tissue with a simple continuous pattern (0 metric polyglecaprone, cutting needle). In the case of long incisions (i.e., C-section), interrupt the continuous pattern at mid-length.

- Apply staples on the skin at every 5 mm.

- Apply a moisture vapor permeable spray dressing over the incision. Then, cover it with sterile gauze. Cover the ventral abdomen with a non-iodophor adhesive drape.

- Immediately on arrival in the recovery stall, hoist the horse and place an abdominal bandage over the adhesive drape. To do so, with the help of an assistant, place a Gamgee cotton over the incision and roll elastic adhesive bands over it and around the abdomen. Finally, apply tape over the elastic band at the cranial and caudal parts of the bandage.

- Place the horse on the floor in lateral recumbency and assist the recovery by chemical restraint and the use of head and tail ropes. Keep the horse under constant surveillance until it is standing and able to walk to its intensive care stall.

2. Routine postoperative protocol (if no complication occurs)

- Management of surgical incision

- Standard abdominal bandage

- Immediately after the recovery from anesthesia, move the horse to a stall in the intensive care unit and remove the entire bandage (including the adhesive drape). Inspect the surgical site and evacuate any subcutaneous blood accumulation by applying gentle pressure using your fingers on the incision.

- Apply a new abdominal bandage: with the help of an assistant, place a Gamgee cotton covered by a layer of antiseptic ointment (containing silver sulfadiazine or nitrofurantoin) in contact with the ventral incision, and 2 rolled Gamgee cotton pads on each side of the dorsal spine (for prevention of pressure sores). Roll elastic adhesive bands around the abdomen. Finally, apply tape over the elastic band at the cranial and caudal parts of the bandage.

- Remove the ventral part of the bandage every 2-3 days. Inspect and palpate the incision. In case of doubt about the soundness of the incision, perform an ultrasonography. Then, place a new Gamgee cotton with an antiseptic ointment over the incision and new elastic bands around the abdomen and over the remaining part of the previous bandage.

- On day 10-11 postoperatively, remove the skin staples after aseptic preparation of the site. Apply a last bandage for 3-5 days. Then, remove this bandage entirely with the help of a liquid adhesive remover (in order to reduce skin irritation).

- Use of negative pressure therapy on a closed incision (alternative to standard bandages)

NOTE: Case selection: The negative pressure therapy is applied over closed incisions that are considered more at risk of developing complications, such as long laparotomy incisions (> 30 cm) for colic surgery or C-section and the incisions of early repeat laparotomies (which are performed through the initial incision).- As soon as the horse is standing steady after recovering from anesthesia, move it to an intensive care stall and tie it up. Remove the entire bandage (including the adhesive drape). Inspect the surgical site and evacuate any blood accumulated subcutaneously by digital pressure on the incision. Apply a thin layer of sterile antiseptic gel (Polyaminopropyl Biguanide) over the incision.

- Apply the negative pressure bandage according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. Measure the length of the incision with the help of a sterile paper ruler (provided in the specific kit). Spray the ventral abdomen with an adhesive spray while the surgical incision is protected by sterile gauze. Then, remove the gauze and leave the glue to pause for approximately 2 min.

- Cut the specific foam dressing of the kit 5 cm longer than the length of the surgical incision. Remove the protective film numbered 1 from the foam dressing. Cut 2 small hydrocolloid strips (also provided in the kit) to adapt the width of the dressing and apply them on the cranial and caudal extremities of the dressing on the side that will be in contact with the skin.

NOTE: Note that the lateral borders of the dressing already have these hydrocolloid strips. - Apply the negative pressure dressing over the surgical incision, with the white tissue side of the dressing in contact with the skin and the purple foam outside. Remove the protective films numbered 2 from the foam dressing.

- Remove the central protective layer numbered 1 on the adhesive drape to expose the adhesive side. Apply the drape over the foam dressing on the ventral abdomen of the horse. Peel the lateral protective layers numbered 1 and pat the drape on the skin to form a seal. Remove the external protective layer numbered 2, and finally, remove the perforated blue handling tabs from the extremities of the drape.

- Apply and slightly overlap several adhesive drapes on the ventral abdomen of the horse to cover the entire dressing and contact the surrounding intact skin over at least 7 cm in all directions to form a seal. Repeat step 2.1.2.5 for each additional drape.

- Pinch the adhesive drapes facing the center of the foam and create a hole of 2 cm diameter with scissors or a scalpel blade by removing the piece of drape. Remove protective layers numbered 1 on the pad and apply it with the pad opening in the central disc directly over the hole in the drapes. Peel protective layer numbered 2. Pat the central disc for adhesion and pull back the external blue tab.

NOTE: It is important to create a hole (and not a slit) large enough to avoid the presence of the remaining parts of the adhesive drape to be in contact with the pad opening. Otherwise, the system will get obstructed. - Suspend the negative pressure therapy machine above the horse and protect the electric cables (also placed above the horse) with isolating foam polyethylene sheaths. Insert the canister into the machine. Connect the pad tubing to the canister tubing.

NOTE: The isolating foam polyethylene sheaths can optionally be covered with tar to prevent the horse from chewing them. - Turn the machine ON. Set the negative pressure at -125 mmHg, on a continuous mode. Check the correct functioning of the negative pressure therapy, which is confirmed by the flattening of the foam facing the wound, the achievement of the desired negative pressure, and the absence of an audible alarm.

NOTE: If leakage is detected, it needs to be identified and patched with additional adhesive drapes until vacuum restoration. In case of obstruction of the system, check all connections, and if the problem remains, remove the adhesive drapes and the pad and replace them with new ones. - When the system is correctly working, apply an abdominal bandage, which is similar to the standard bandage described in step 2.1.1.2. with two exceptions: 1) it does not contain any antiseptic ointment on the ventral Gamgee cotton and 2) a supplemental Gamgee cotton is applied underneath the tubing where it is still close to the horse abdomen, to avoid pressure sores. Keep the horse tied up all the time while on negative pressure therapy.

- Remove the negative pressure bandage after 2-3 days. Check the wound while carefully respecting aseptic conditions and place a new negative pressure bandage for 2-3 additional days. Thereafter, definitively remove the negative pressure bandage and replace it with a standard bandage (see step 2.1.1.2.). Follow the steps previously described in 2.1.1.3 and 2.1.1.4. for the remaining part of the incision management.

- Standard abdominal bandage

- Postoperative treatments

- In addition to intravenous fluid therapy, administer postoperative treatments, which consist of IV gentamicin (6.6 or 8.8 mg/kg every 24 h) and penicillin (20,000 IU/kg: either sodium penicillin IV every 6 h or procaine penicillin intramuscularly [IM] - every 12 h) for 5-7 days; non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (flunixin meglumine 1.1 mg/kg IV every 12 h) for 4-5 days and enoxaparin (150 mg/ 500 kg bodyweight subcutaneously every 24 h) for 3 days.

NOTE: The duration of the postoperative treatments and the addition of other treatments (such as prokinetic drugs, supplemental analgesics, oxytocin, etc.) need to be adapted for each animal, taking into account the animal's evolution and the potential presence of complications.

- In addition to intravenous fluid therapy, administer postoperative treatments, which consist of IV gentamicin (6.6 or 8.8 mg/kg every 24 h) and penicillin (20,000 IU/kg: either sodium penicillin IV every 6 h or procaine penicillin intramuscularly [IM] - every 12 h) for 5-7 days; non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (flunixin meglumine 1.1 mg/kg IV every 12 h) for 4-5 days and enoxaparin (150 mg/ 500 kg bodyweight subcutaneously every 24 h) for 3 days.

- Rehabilitation

- Strictly confine the horse to a stall for 10 days. Work on the following recommendations for rehabilitation: 8 weeks of stall rest with hand walks (1-2 times a day, starting from 10 min to 30 min at the end of the recovery period) before exercise or pasture turnout can progressively be resumed.

NOTE: During the last 4 weeks of rest and hand walking, a protocol of exercises adapted from Holcombe et al.19 and Clayton20 can be used. This is optional and left at the discretion of the owner/rider.

- Strictly confine the horse to a stall for 10 days. Work on the following recommendations for rehabilitation: 8 weeks of stall rest with hand walks (1-2 times a day, starting from 10 min to 30 min at the end of the recovery period) before exercise or pasture turnout can progressively be resumed.

3. Management of infection over the entire length of the incision by a negative pressure therapy

NOTE: Clinical signs for which to perform this: Incisional purulent or sero-purulent discharge, incisional tenderness with subcutaneous fluid pocket along the incision (detected by ultrasonography), and collection of purulent material when this liquid is aspirated (with needle and syringe).

- If necessary (presence of hairs longer than a few mm), shave the skin around the incision. After aseptic preparation, re-open the skin and subcutaneous tissues to drain the secretions. Perform a bacteriological culture and sensitivity test either by swabbing the depth of the infected incision or by collecting the purulent material with a sterile needle and syringe before opening the skin and subcutaneous tissues.

- Debride the wound: Remove any infected tissue or biofilm by curettage and flush with a sterile isotonic solution. Apply a thin layer of sterile 0.1% polyaminopropyl biguanide gel on the cleaned wound.

- Apply the negative pressure bandage according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. Measure the length of the incision with the help of a sterile paper ruler. Apply an adhesive spray on the ventral abdomen while the open wound is protected by sterile gauze. Then, remove the gauze and leave the glue to pause for approximately 2 min.

- Cut a piece of silver foam to the exact dimensions of the wound and place this foam on the wound and inside the cutaneous rims. Make sure that the foam does not overlap intact skin.

- Follow the next steps of the placement of the negative pressure bandage as previously described (steps 2.1.2.5. to 2.1.2.10.).

- Place an abdominal hernia belt (without additional ventral reinforcement, but with the thick dorsal foam pad) over the elastic bandage to prevent/reduce the risk of abdominal hernia formation. Note that a breast collar is rarely necessary.

- Change the negative pressure therapy bandage every 3-4 days. At each bandage change, perform a debridement of the wound (if needed) and remove any very loose suture material.

NOTE: It is important to avoid letting the same foam come in contact with the wound for longer than 5 days because granulation tissue will grow inside the small holes of the foam, causing difficulties in removing the foam and bleeding after foam removal. - Continue the negative pressure therapy until almost all the abdominal incision is covered by granulation tissue. This usually takes no more than 2 weeks.

- When the negative pressure therapy is stopped, let the horse carry out free movements in the stall. Provide daily wound care (debridement and removal of the secretions).

- On the first day, place a standard elastic abdominal bandage (see step 2.1.1.2.) covered by a hernia belt (and dorsal foam). For the next days, after removal of the ventral part of the abdominal bandage and the wound cleaning, only cover the wound with a Gamgee cotton with antiseptic ointment (hold in place with a few stripes of large tape) and the hernia belt. This lighter bandage reduces the cost of numerous elastic bands. The hernia belt brings some support and protection to the wound.

- Adapt the duration or the type of medical treatments (antimicrobial and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) to the wound evolution (usually ~ 10-15 days).

- Work on the following recommendations:

- Strict stall rest until complete wound healing (with wound care and hernia belt support - see step 3.9).

- Up to 1 month of stall rest and wearing of the hernia belt without additional ventral reinforcement (which is a curved plastic piece to be placed in the ventral pocket) with daily walks: starting with 5 min of walk per day during the first week, with 5 min increment with every additional week.

- The following month, the horse continues to wear the hernia belt, but the curved plastic piece (with the convex aspect towards the abdomen) is placed in the ventral pocket of the hernia belt. The stall rest is continued, but the frequency of the walk sessions progressively increased to 3-4 times a day. During this month, a program of exercises adapted from Holcombe et al.19 and Clayton20 is recommended.

- After this period, the horse can progressively resume all activities (light work, pasture turnout) if there is no significant abdominal hernia.

NOTE: When the infection is localized to a small area without involving the entire length of the incision, negative pressure therapy can be instituted on the smaller open wound or can be avoided (left at the surgeon's preference). If the negative pressure therapy is not used, local care (as in step 3.2) is performed every day, and the bandage is the same as in step 3.9.

4. Management by retention sutures for subacute breakdown of the incision secondary to severe infection

NOTE: Clinical signs for which to perform this: Severe infection of the entire incision, with loosening of the sutures on the linea alba, gap formation in the linea alba incision allowing the introduction of one or more fingers through it, and abnormally large quantities of fluid (i.e., 300 mL/day) draining in the bandage or aspirated in the negative pressure therapy canister.

- Surgical preparation and technique

- Give the horse preoperative broad-spectrum antibiotics (based on previous culture and sensitivity), flunixin meglumine (1.1 mg/kg IV), and subcutaneous enoxaparin (150 mg/500 kg of body weight). Protect the infected laparotomy incision with an abdominal bandage. After induction of general anesthesia, place the horse in dorsal recumbency.

NOTE: If sodium penicillin is used, repeat it every 90 min. - Place a urinary catheter. For males, after placement of a stack of 4 inch x 4 inch gauze pads, close the prepuce using Backhaus towel clamps.

- Prepare the abdomen aseptically, around the incision, scrub for 5 min scrub with 3.75% povidone-iodine or 4% chlorhexidine digluconate soap, and rinse only at the end with 70% isopropyl alcohol. Finally, apply 3% povidone-iodine in isopropyl alcohol solution spray. On the infected incision, scrub for 5 min with 0.5% dermic povidone-iodine.

- Double drape the abdomen, place an iodophor adhesive film on the intended surgical site, and drapes from a universal pack around. Then, cover them with a laparotomy drape with incise film on its center.

- Remove all remaining sutures on the linea alba. Perform a new bacteriological culture on the wound. Remove all infected tissues by sharp dissection (removal of the edges of the previous incision of the linea alba) and the liquid material (blood, etc.) using a surgical aspirator. Cautiously dissect potential adhesions between the bowels and the infected wound.

- Change gloves and apply new sterile drapes. Rinse copiously the edges of the incision and the abdomen with isotonic sterile electrolytes solution (lactated Ringer solution) at 37 °C while fluids are continuously aspirated.

- Evaluate abdominal viscera and perform adhesiolysis, if needed. Perform omentectomy if the greater omentum has not been removed during the previous surgery. Before closure, fill the abdomen with 5 L of lactated Ringer solution added with 75,000 IU of heparin.

- For the retention sutures, cut several segments of sterile stainless steel cerclage wire of 1 mm diameter at a length of 50-60 cm.

- Preplace them in an interrupted vertical U mattress pattern 3 cm apart through the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscular layer while excluding the retroperitoneal fat and peritoneum, using a 14G, 8 cm long needle as a wire passer.

- To do so, place the far suture 5 cm away from the wound edge and the near suture 2.5 cm away from the wound edge. On the opposite side from the future knot, pass the loop of the cerclage wire through a 2.5 cm section of plastic tubing to obtain a buttress effect.

- Once all the cerclage wires are preplaced, preplace several retention sutures of 6 metric polyglactin 910 in between the cerclage wire.

NOTE: This second series of retention suture is placed the same way as the cerclage wire but without the plastic tubing and without the need to use a 14G needle to pass through the tissues as the needle is already attached to the suture thread. - While an assistant keeps all the retention sutures of polyglactin 910 under tension to obtain the apposition of the edges of the incision, knot each of them separately.

NOTE: This step allows an easier apposition of the edges of the incision because cerclage wires are more difficult to manipulate and put under tension the first time. - Then, while all the cerclage wires are kept under maximal tension by 1-2 assistant(s), twist (manually first and then with a pair of flat-nosed pliers) the ends of each vertical mattress separately.

- Cut the ends of each wire with cutting pliers at 3 cm length, then tuck and glue the cut ends of the wires into a section of plastic tubing. Remove the sutures of polyglactin 910. Do not suture the subcutaneous tissue and the skin to allow for drainage.

- Apply a moisture vapor permeable spray dressing over the incision. Then, cover it with sterile gauze. Cover the ventral abdomen with a non-iodophor adhesive drape.

NOTE: The recovery from anesthesia is the same as in steps 1.2.8. and 1.2.9. with the addition of a hernia belt (without additional ventral reinforcement) over the elastic bandage.

- Give the horse preoperative broad-spectrum antibiotics (based on previous culture and sensitivity), flunixin meglumine (1.1 mg/kg IV), and subcutaneous enoxaparin (150 mg/500 kg of body weight). Protect the infected laparotomy incision with an abdominal bandage. After induction of general anesthesia, place the horse in dorsal recumbency.

- Postoperative management

- As soon as the horse is standing steady after the recovery from anesthesia, move it to an intensive care stall and tie it up. Remove the entire bandage, including the adhesive drape. Dry the surgical site with sterile gauze.

- Apply the negative pressure therapy using the procedures described in steps 3.3 to 3.6, with the only difference that the foam is not cut to adapt the dimensions of the wound but covers the ventral incision and the metallic sutures altogether.

- Change the negative pressure therapy bandage the first postoperative day and then every 3-4 days until the edges of the ventral incision are united by a healthy granulation tissue (approximately 8 days).

- When the negative pressure therapy is definitively stopped, let the horse free in the stall. Place a standard elastic abdominal bandage (see step 2.1.1.2.) covered by a hernia belt (and dorsal foam). Change the ventral part of this bandage every 2-3 days for wound care (wound debridement and removal of the secretions).

NOTE: The initial incision is usually not producing most of the secretions. The main secretions come from the abaxial cerclage wires and bolsters that become progressively embedded in granulation tissue. - Remove cerclage wires and bolsters when they no longer provide support because they are cutting through the skin. After aseptic preparation, perform a staged removal by cutting the cerclage wires with cutting pliers on the standing sedated horse (on days 13 and 16).

- Continue the wound care every other day until complete healing of all wounds: the ventral midline wound and the abaxial wounds that occurred secondary to the placement of the cerclage wires. Maintain the standard elastic bandage and the hernia belt.

- Adapt the duration of medical treatments (antimicrobial and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) to the evolution of the wound (approximately 3-4 weeks).

- Perform rehabilitation as done in step 3.11.

Figure 1: Decision tree. The decision tree for management of laparotomy incisions and their potential complications. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Results

Routine surgical technique for closure of the abdominal incision and postoperative management: Our technique of closure of the linea alba and routine postoperative management have only undergone minor adaptations since their publication in 20203.

Therefore, for horses operated for abdominal pain, the results presented here are those of this retrospective study³, involving 606 laparotomies performed in 564 horses presenting colic signs during the study period. The mean length of the laparotomy incision was 17.5 cm. This publication revealed 9.5% (52/546) incisional complications after a single laparotomy and 33.3% (10/30) after a repeat laparotomy. The incisional complications were serous to serosanguineous discharge (n=19), hematoma (n=3), sinus suture tract/ localized infection (n=9), superficial infection over more than 1/3 of the incision (n=27), complete wound breakdown due to deep incisional infection and septic peritonitis (n=1), acute linea alba and subcutaneous dehiscence due to a fall (n=1) and hernia formation without infection (n=2). Therefore, the previous study 3 reported an actual incisional infection occurrence after single and repeat laparotomy of 5.3% and 26.7%, respectively.

| Short term complications (n= 606 laparotomies) | ||

| single laparotomies (n= 546) | repeat laparotomies within 4 weeks (n= 30) | |

| serous/ sero-sanguinous discharge | 17 | 2 |

| hematoma | 3 | 0 |

| sinus suture tract/ localized infection | 9 | 0 |

| superficial infection > 1/3 incision | 20 | 7 |

| wound breakdown < septic peritonitis | 0 | 1 |

| acute linea alba and subcutaneous dehiscence < fall | 1 | 0 |

| hernia formation without infection | 2 | 0 |

| total incisional complications | n= 52 (9.52%) | n= 10 (33.33%) |

| actual incisional infection | n= 29 (5.31%) | n= 8 (26.67%) |

Table 1: Detailed postoperative incisional complications after single and repeat ventral midline laparotomy in horses with colic. This table summarizes results from Salciccia at al.³.

The long-term follow-up (≥ 12 weeks postoperatively; n= 417) of this study3 revealed 1.68% of clinically relevant wound complications: a small hernia (≤ 5 cm diameter) in 4 cases and a large hernia in 3 cases.

For C-section results, we reviewed the medical records of mares that underwent a cesarean section between the 1st of January 2013 and the 31st of December 2022 and used the same inclusion criteria as the study on colic horses3 (i.e., survival ≥ 7 days postoperatively and no preexisting lesion of the ventral abdominal wall). Our C-section case load is very low in comparison to the colic surgery caseload. Only 12 mares (median weight: 636 kg) met the inclusion criteria. The mean length of the laparotomy incision was 38 cm. Incisional complications were: serous discharge resolved within 4 days (n=1), sinus suture tract/ localized infection (n=1), partial linea alba, and subcutaneous dehiscence due to a violent and very long recovery from anesthesia (n=1). This horse was reoperated (complete closure of all incisional layers) and developed a superficial wound infection. At reevaluation 3 months postoperatively, the infection had resolved, and no abdominal hernia was present.

Use of the negative pressure therapy on a closed incision (for prevention of infection):

In order to evaluate the potential efficacy of this therapy among the cases treated by this technique in the clinic, we determined inclusion and exclusion criteria (over a 3-year period starting on the 1st of January 2020).

Inclusion criteria: Cases considered more at risk of infection (early relaparotomies - i.e., within 7 days after the first surgery- or laparotomy incisions longer than 30 cm) and survival at least 7 days postoperatively. Application of negative pressure therapy immediately after recovery from anesthesia.

Exclusion criteria: Small animals (donkeys and ponies < 250 kg), foals younger than 1 year.

A total of 8 horses met the inclusion criteria (6 early relaparotomy and 2 long incisions). Out of them, 5 did not experience incisional complications (4 relaparotomy and 1 long incision), and the other 3 developed an incisional infection. Over the same period, 4 horses initially met the inclusion criteria but were excluded because of severe pain or fractious temperament precluding the correct application and functioning of the system. Out of them, 1 of 3 relaparotomies and 1 of 1 long incision became infected.

Although results do not appear different between the two groups, the size of the groups precluded statistical analysis, and the non-effectiveness of the system needs to be evaluated and confirmed with larger groups. Results on animals that were not included for various reasons, such as late application of the system or indications other than that listed in the protocol (i.e., severe edema, contaminated surgery, etc.) left the clinicians under an overall positive impression.

Use of negative pressure therapy for treatment of an infected laparotomy incision:

Over the last 11 years, negative pressure therapy was applied for the treatment of infected laparotomy incision or recurrent seroma on 50 horses. The associated protocol of management was refined with the use of a hernia belt for the last 3 years and the introduction of the optional protocol of exercise (adapted from Holcombe et al.19 and Clayton20) only since last year.

In the majority of cases, negative pressure therapy was applied for 7-10 days. Although there were no control groups (without the use of negative pressure therapy), we had the positive clinical impression that it accelerated granulation tissue formation and reduced the soaking of the bandages by the continuous aspiration of secretions. A few horses continued to produce only residual purulent secretions for few weeks after negative pressure therapy was discontinued.

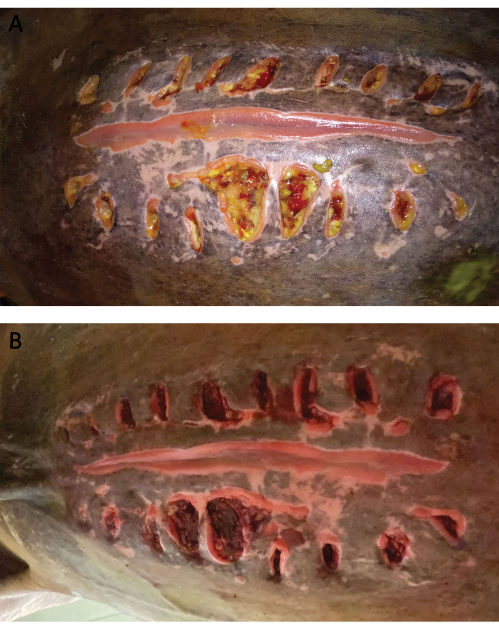

The evolution of infected laparotomy incisions treated by NPWT is illustrated for 2 horses (Horse 1: Figure 2A-C; Horse 2: Figure 3A-B).

Figure 2: Laparotomy Incision of Horse 1. (A) Horse 1: Infected laparotomy incision. The cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues have been reopened to allow drainage of the secretions. (B) Horse 1: Laparotomy incision treated by negative pressure therapy (with silver foam, adhesive drape, and pad tubing in place). (C) Horse 1: Appearance of the laparotomy incision 1 day after the beginning of the negative pressure therapy. Note that the granulation tissue is more vascularized (redder) and has an alveolar aspect, which is caused by contact with the small holes in the silver foam. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Laparotomy Incision of Horse 2. (A) Horse 2: Infected laparotomy incision. The cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues have been reopened. A portion of the linea alba (with some muscular sutures) is visible in the center of the wound. (B) Horse 2: Appearance of the laparotomy wound 16 days later. The defect is almost completely filled with granulation tissue, although a part of the linea alba still needs to be covered. The alveolar aspect of the granulation tissue is typical of the imprint of freshly removed foam of the negative pressure therapy. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

This therapy did not suffice to prevent the complete breakdown of the incision in 3 horses that experienced severe infection. Out of those, 2 were euthanatized, and 1 was operated thereafter with the retention sutures described above. Furthermore, some horses were euthanatized for other complications (i.e., recurrent severe pain, etc.) while still under negative pressure therapy, leading to incomplete evaluation of this therapy on an infected laparotomy incision.

Several horses developed a mild to moderate deformation of the ventral abdomen following the incisional infection. However, when excluding the horse treated by retention sutures, none of the horse treated by negative pressure therapy and hernia belt developed a significant abdominal hernia requiring corrective surgery.

Management of complete wound breakdown by retention sutures:

As described in the literature6,9, complete breakdown of the laparotomy incision is rare. The case described here (horse, gelding, Zangersheide, 492 kg) underwent a first laparotomy, during which a typhlotomy and manual evacuation of the dry cecal content was performed to correct a severe cecal impaction (in addition to a small intestine volvulus). Although a negative pressure therapy was applied to the laparotomy incision following the development of an infection, the horse presented a progressive breakdown of the incision and was reoperated according to the technique described above. During surgery, adhesions between the cecal body and the laparotomy incision, as well as between the cecal apex and the right ventral colon, were detected and resected. The postoperative period in the clinic was uneventful.

The horse was re-examined 15 months postoperatively. According to the rider, all the recommendations were followed after discharge from the clinic, except the ventral reinforcement (a curved plastic piece) that was not placed in the ventral pocket of the hernia belt because the horse presented some discomfort with it. Sequelae from the surgery are scars and several small hernias at the location of the previous retention sutures that significantly decrease the cosmetic appearance of the horse. However, the horse fully recovered to his original level of sports performance (jumping 120 cm) and is still trained to further improve. No postoperative signs of colic have been reported since discharge from the hospital.

The evolution of the laparotomy incision of this horse is illustrated in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 (during hospitalization), and Figure 7 (15 months after the surgery).

Figure 4: Aspect of the wound of the horse treated by retention sutures. (A) The aspect of the wound on day 1 postoperatively. Note the stainless-steel wires protected by bolsters on both sides of the incision. (B) Aspect of the wound at day 5 postoperatively. Negative pressure therapy has been instituted right after recovery from anesthesia. The wound is partly filled with pink granulation tissue. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5: Aspect of the wound of the horse treated by retention sutures. (A) Aspect of the wound at the time of removal of the retention sutures and bolsters (day 16 postoperatively). The edges of the laparotomy incision are united and covered by healthy granulation tissue. However, the wires and bolsters have progressively cut through the skin, causing secondary wounds that produce most of the secretions. (B) The aspect of the wound on the same day after debridement of the abaxial wounds created by the wires and bolsters. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 6: End of hospitalization for horse treated by retention sutures. (A) Aspect of the wound at day 42 postoperatively (end of hospitalization). (B) Lateral view of the abdomen on the same day. No ventral deformation is observed. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 7: Follow-up of horse treated by retention sutures. (A) Ventral view of the abdomen at 15 months postoperatively. The laparotomy incision has closed without complication, but several small hernias have developed on the former locations of the retention sutures and bolsters (especially on the cranial part of the abdomen). (B) Lateral view of the abdomen on the same day. The abdomen does not present a large deformation, but several small hernias are visible on both sides of the cranial part of the laparotomy incision. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

In our clinic, the technique for closure of the equine abdomen is based on a combination of an interrupted vertical U mattress and apposition sutures on the linea alba. In our experience, disadvantages associated with an interrupted pattern suture, such as a greater amount of suture material within the incision and a slower application5, are balanced by several other advantages. Interrupted vertical mattress sutures are particularly indicated for regions under tension and at risk of infection21,22, such as the abdomen of colic horses. They result in minimal compromise to the local microcirculation23. Finally, breakage of the suture material only impacts individual stitches, and the risk of evisceration or hernia formation is therefore assumed to be decreased, when compared to the continuous pattern.

Applying interrupted sutures to our incisions of colic celiotomies does not take a lot of extra time because these wounds are relatively small (17.5 cm on average³). However, the addition of interrupted sutures probably has a greater impact on the duration of surgery on long incisions, such as in C-sections (38 cm on average for our cases). Therefore, since the last report3, methods to save more time have been implemented. These include the replacement of interrupted apposition sutures in between the vertical U mattress sutures by a simple continuous pattern over the vertical mattress sutures and the selective use of staples for skin closure, which was shown not to be a risk factor for surgical site infection3.

Despite the subcutaneous dissection, which has been reported as a potential risk factor for infection24 but is necessary to create enough space for ideal placement of the vertical sutures, the adequacy of the selected closure method is illustrated by low infection and low herniation rates3.

For more than 20 years, we have used elastic bandages to protect laparotomy incisions before the animals recovered from anesthesia. The benefits of an abdominal bandage have since been demonstrated25. Studies have also suggested that contamination of the laparotomy incision mainly occurs during recovery, especially if of poor quality26,27. As the bandage is applied on a flexed abdomen while the anesthetized horse is hoisted, the fitting of this bandage is often not optimal. Even if it brings some degree of mechanical support to the abdomen during recovery, it frequently slips backward, partially exposing the cranial part of the incision. To better protect the incision at this crucial time, we cover it with an adhesive drape under the elastic bandage, which, based on observations, greatly reduces the exposure of the surgical wound.

Just after recovery, horses are often soaked and sweating. These conditions create a moist environment under the bandage, which may increase the risk of contamination. For this reason, the entire temporary bandage and adhesive drape are removed, the incision and surrounding skin are dried, and a new, fresh, adhesive elastic bandage is applied to the standing animal.

Although they are more expensive, we prefer the use of adhesive elastic rolls to non-adhesive elastic wrap for the bandages. They particularly prove beneficial in the early postoperative period, as they offer better support of the ventral abdomen, which minimizes peri-incisional edema that could be a cause or a consequence of surgical site infection12. Moreover, adhesive bandages do not slip caudally and thus avoid exposure to the incision.

However, as the adhesive elastic bandages are sticky and tightly applied, they have several drawbacks, such as pressure sores on the back and hair removal/skin irritation caused by frequent changes. To reduce these side effects, three critical steps are: (1) applying large Gamgee protections on each side of the dorsal spine, (2) removing only the ventral part of the bandage when inspecting the incision every other day, and (3) using a glue remover for the final removal of the entire bandage. Infected and breakdown cases require prolonged abdominal bandaging, which increases the costs and skin irritation caused by repeated removals. In those cases, lighter bandages are applied over the incision, and a hernia belt is placed to maintain a ventral support of the abdomen12 and reduce the risk of hernia formation. Because of their thicker and stiffer material, the hernia belts are sometimes not perfectly fitted, leaving a gap between the caudal part of the ventral abdominal wall and the belt, leading to urine accumulation in the bandage of some males. Another problem with hernia belts is that they can cause heat rash and pressure soreness when worn for a long period. Therefore, we usually advise removing the belt 1-2 h a day once the ventral incision has healed.

Negative pressure therapy has been used for more than 10 years on open wounds in our clinic, with a pressure of -125 mmHg as most frequently recommended in the literature28. One of the major issues with the NPWT is to achieve and maintain a perfect seal on the wound on a moving horse. To reduce the risk of air leakage, we have made some adaptations to the technique over the years, like other authors did29. Spraying an adhesive glue around the wound and applying an elastic bandage over the drapes increase the adhesion of the plastic drapes. Cross-tying the animal helps to restrain its movements. Although negative pressure can be applied in an alternative mode, we always use the continuous mode to keep continuous aspiration on the drapes, assuming that it will reduce the risk of loss of adhesion when the region is submitted to movements. Several models of portative machines that can be fixed on horseback are available. In our clinic, we prefer using machines plugged into mains that are suspended above the horse. This avoids the risk of low battery, leading to the accumulation of secretions underneath the drapes and their possible later detachment. It also limits the manipulation and reduces the risk of damage to the machine.

The use of the device on abdominal incisions is most indicated as, in comparison to other locations (limbs, neck), the negative pressure system is easier to apply, and leakage is less frequent, probably because of lesser movements and a regular geometry of the abdomen.

One problem of NPWT in horses is that, in the long run, the glue and the plastic drapes lead to progressive skin irritation, sometimes with substantial amounts of serous secretions. That sometimes compromises the adhesion of the plastic drapes and therefore leads to treatment interruption. We rarely observe this problem within the first 2 weeks, but this can, of course, vary between cases, mainly depending on skin quality.

According to the literature, negative pressure therapy improves the healing of open wounds by promoting the early appearance of a smooth granulation tissue bed14,28. This is also our clinical impression of infected cases. However, this is a non-standardized study, where all animals were client-owned and which obviously did not include a control group, precluding statistical analyses. While negative pressure therapy has been described in open wounds on limbs and some other regions in horses29,30,31, no other reports on the management of infected equine abdominal wounds with this therapy appear to be available in the literature for comparison.

The increased costs of this therapy, in comparison to routine elastic bandages, are somehow balanced by the less frequent bandage changes (every 3-5 days vs. everyday with routine bandages), as well as by a rapid formation of granulation tissue.

Negative pressure therapy was easier to apply on a closed incision than on an open one, but as reported in a previous paper on horses32, it did not reduce the infection rate. This does not agree with some reports in humans15,16 and probably needs to be further confirmed in a larger study.

The management of the single case of a complete breakdown of the laparotomy incision was adapted from the usual reported technique18. Changes included the replacement of the standard use of 18G-22G stainless steel wire on a large cutting needle by a 1 mm stainless steel cerclage wire not swaged. We used a 14G needle that was preplaced at the intended location through the tissues, and the cerclage wire was passed through the needle cannula as it is withdrawn in a fashion similar to that described in the fixation of the rostral part of the mandible or maxilla by the Obwegeser technique33. We also found that using retention sutures of polyglactin 910 maintaining the edges of the incision closer greatly eased manipulation of cerclage wire, which can be challenging because of its rigidity. We also innovated by using negative pressure therapy postoperatively. This allowed continuous aspiration of the secretions and prevented recontamination of the incision by environmental bacteria. In addition, it only needed changing every 3 days, thus reducing the costs by comparison with the daily changes that are necessary for the routine bandages. Finally, the use of a hernia belt supplied mechanical support to the incision, minimizing (but not avoiding) the subsequent hernia formation.

In conclusion, the surgical technique of the equine abdomen closure, the postoperative protocol, and the adjustment we implemented allow for low incisional complication rates and overall successful management of incisional complications, should they occur. Fine-tuning of existing protocols or new methods to further reduce complication rates is still currently under development but should benefit from a multicentric study to allow comparisons between centers.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest with any company trading one of the above-mentioned products.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Jennifer Romainville and Cyrielle Bougeard for their technical help during procedures and all members of the Clinic (especially the anesthetists, residents in surgery, interns, students, and grooms) for their assistance and care to the patients. The owners of the horse operated with the retention sutures are also thanked for answering the long-term follow-up questionnaire and allowing taking pictures of the horse. Finally, the authors thank M. Laurent Leinartz for his help in editing the pictures.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 300 ml canister (with gel) for ACTIV.A.C. Therapy system | KCI | M8275058/5 M8275058/10 | canister for negative pressure therapy |

| Alfatec 6 HRTX 50 | Prodivet Pharmaceutical produced by Chirina T Injecta | PG0649P | 6 metric polyglactin 910 |

| Appose ULC Slim Body Skin Stapler | Covidien | 88868037 12 | skin staples |

| AquaPharm NaCl 1l | Ecuphar | 366 4174 | 1 L saline |

| Bovivet reinforced disposable needle 14G x 3 1/4'' . 2.1 x 80 mm | Kruuse | 112462 | needle used when placing the stainless steel retention sutures |

| Buster Surgery Cover 120 cm x 180 cm | Kruuse | 141 850 | surgical drapes |

| Clexane 15.000 UI | Sanofi | BE-230185 | enoxaparin |

| CM Hernia Belt | CM Equine Products | Hernia belt: various sizes, to be adapted to the horse's dimensions | |

| Cutting plier 24 cm maxi 3 mm 1456 | Alcyon | 8387671 | cutting plier |

| Dermanios Scrub | Anios | BE-REG-00679 | Chlorhexidine digluconate soap |

| Dermincise 80 cm x 60 cm | Vygon | 38 80 60 | non-iodophor adhesive drape |

| Digital Ultrasonic Diagnostic Imaging System | Mindray | DP-50Vet | ultrasound machine |

| e band | Millpledge | DQ05100 | elastic adhesive roll |

| Ethanol 70% | Savetis | Isopropyl alcohol | |

| Fil de cerclage AO 1 mm x 10 m | Alcyon | 8022030 | 1 mm diameter stainless steel cerclage wire |

| Flammazine 1% creme | Alliance Pharma | BE270505 | silver sulfadiazine dressing |

| Flat-nosed pliers 180 mm | Alcyon | 8368113 | flat-nosed pliers |

| Furacine Soluble Dressing | Limacom nv | BE300876 | nitrofurantoin dressing |

| Genta Equine 100 mg/ml | Divasa-Farmavic | BE-101491 | gentamicin |

| Heparine Leo 5000 U.I./ml | Leo | 1361-559 | heparin |

| Info.V.A.C. | KCI | 413781 Rev B | negative pressure therapy machine |

| Intrafix Primeline | B Braun | 4062182 | plastic tubing (for buttress effect for retention sutures) |

| Ioban 56 cm x 60 cm | 3M | 6648EU | iodophor adhesive film |

| Iso-Betadine Dermicum | Mylan | BE007077 | dermic povidone iodine |

| Iso-Betadine Savon | Mylan | BE007095 | Povidone iodine soap |

| Kruuse adhesive spray | Kruuse | 141865 | adhesive spray |

| Laparotomy Sheet with Incise Film Eclipse | Medline | 29511CEA | laparotomy drape with incise film |

| Leukotape Classic | BSN medical | 01703-00 | adhesive tape |

| Leukotape Remover | BSN medical | 97285-05 | Liquid adhesive remover |

| Meganyl 50 mg/ml | Syva | 4117-446 | flunixine meglumine |

| Monocryl 0 CP-1 | Ethicon | C267 | 0 metric polyglecaprone, cutting needle |

| Opsite | Smith and Nephew | 66004978 | Moisture vapour permeable spray dressing |

| Penicilline 5.000.000 UI | Kela | 7E33729E19 | Sodium Penicillin |

| Peni-Kel 300.000 UI/ml | Kela | 1370-881 | Procain Penicillin |

| Poviderm Sol | Emdoka | BE-V196971 | Povidone iodine in isopropyl alcohol solution |

| Prevena Plus Customizable dressing | KCI | PRE4055 | Kit for negative pressure therapy on closed wounds |

| Prontosan | B Braun | 400 505 | Gel continaing 0,1% Polyaminopropyl Biguanide (polihexanide) |

| Saddle pad (equine size) | CM Equine Products | SP-E1 | large foam pad for protection of the horse's back |

| SENSAT.R.A.C. Pad | KCI | M8275057/10 | Pad with central disc for negative pressure therapy |

| Thilo-Tears | Alcon NV | 233866 | Polymer eye ointment |

| Universal Pack Eclipse | Medline | 29105CEA | universal pack (drapes) |

| V.A.C. Drape | KCI | M6275009/10 | adhesive drape for negative pressure therapy |

| V.A.C. Granufoam silver Dressing | KCI | M8275099/5 M8275099/10 | silver foam for negative pressure therapy |

| Vetivex Ringer Lactate solution 5000 ml | Dechra | BE-V442032 | 5 L Pouch of Lactated Ringer's Solution |

| Vicryl 2 CTX | Ethicon | V367H | 2 metric polyglactin 910 |

| Zorbo-G-Padding | Millpledge | DX05200 | Gamgee cotton |

References

- Marshall, J. F., Blikslager, A. T., JA, A. u. e. r., Stick, J. A., Kümmerle, J. M., Prange, T. Colic: Diagnosis, Surgical Decision, Preoperative Management, and Surgical approaches to the Abdomen. Equine Surgery (5th edition). , 521-528 (2019).

- Woodie, J. B., JA, A. u. e. r., Stick, J. A., Kümmerle, J. M., Prange, T. Uterus and ovaries. Equine Surgery (5th edition). , 1083-1094 (2019).

- Salciccia, A. Complications associated with closure of the linea alba using a combination of interrupted vertical mattress and simple interrupted sutures in equine laparotomies. Vet Rec. 187 (11), e94 (2020).

- Salem, S. E., Proudman, C. J., Archer, D. C. Prevention of post operative complications following surgical treatment of equine colic: Current evidence. Equine Vet J. 48 (2), 143-151 (2016).

- Mair, T. S., Smith, L. J., Sherlock, C. E. Evidence-based gastrointestinal surgery in horses. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 23 (2), 267-292 (2007).

- Fogle, C., JA, A. u. e. r., Stick, J. A., Kümmerle, J. M., Prange, T. Postoperative care, complications, and reoperation of the colic patient. Equine Surgery (5th edition). , 660-677 (2019).

- Dunkel, B., Mair, T., Marr, C. M., Carnwath, J., Bolt, D. M. Indications, complications, and outcome of horses undergoing repeated celiotomy within 14 days after the first colic surgery: 95 cases (2005-2013). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 246 (5), 540-546 (2015).

- Ingle-Fehr, J. E., Baxter, G. M., Howard, R. D., Trotter, G. W., Stashak, T. S. Bacterial culturing of ventral median celiotomies for prediction of postoperative incisional complications in horses. Vet Surg. 26 (1), 7-13 (1997).

- Freeman, D. E., Rötting, A. K., Inoue, O. J. Abdominal closure and complications. Clin Tech Equine Pract. 1 (3), 174-187 (2002).

- Rinnovati, R., Romagnoli, N., Stancampiano, L., Spadari, A. Occurrence of incisional complications after closure of equine ventral midline celiotomies with 2 Polyglycolic acid in simple interrupted suture pattern. J Equine Vet Sci. 47, 80-83 (2016).

- Torfs, S., et al. Risk factors for incisional complications after exploratory celiotomy in horses: do skin staples increase the risk. Vet Surg. 39 (5), 616-620 (2010).

- Canada, N. C., Beard, W. L., Guyan, M. E., White, B. J. Comparison of sub-bandage pressures achieved by 3 abdominal bandaging techniques in horses. Equine Vet J. 47 (5), 599-602 (2015).

- Agarwal, P., Kukrele, R., Sharma, D. Vacuum assisted closure (VAC)/negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) for difficult wounds: A review. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 10 (5), 845-848 (2019).

- Stanley, B. J. Negative pressure wound therapy. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 47 (6), 1203-1220 (2017).

- Dyck, B. A. Use of incisional vacuum-assisted closure in the prevention of postoperative infection in high-risk patients who underwent spine surgery: a proof-of-concept study. J Neurosurg Spine. 31 (3), 430-439 (2019).

- Scalise, A., et al. Improving wound healing and preventing surgical site complications of closed surgical incisions: a possible role of incisional negative pressure wound therapy. A systematic review of the literature. Int Wound J. 13 (6), 1260-1281 (2016).

- Heller, L., Levin, S. L., Butler, C. E. Management of abdominal wound dehiscence using vacuum assisted closure in patients with compromised healing. Am J Surg. 191 (2), 165-172 (2006).

- Toth, F., Schumacher, J., JA, A. u. e. r., Stick, J. A., Kümmerle, J. M., Prange, T. Abdominal hernias. Equine Surgery (5th edition). , 645-659 (2019).

- Holcombe, S. J., Shearer, T. R., Valberg, S. J. The effect of core abdominal muscle rehabilitation exercises on return to training and performance in horses after colic surgery. J Equine Vet Sci. 75, 14-18 (2019).

- Clayton, H. M. Core training and rehabilitation in horses. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 32 (1), 49-71 (2016).

- Weiland, D. E., Bay, R. C., Del Sordi, S. Choosing the best abdominal closure by meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 176 (6), 666-670 (1998).

- Gupta, H., et al. Comparison of interrupted versus continuous closure in abdominal wound repair: a meta-analysis of 23 trials. Asian J Surg. 31 (3), 104-114 (2008).

- Provost, P. J., Bailey, J. V., JA, A. u. e. r., Stick, J. A. Principles of plastic and reconstructive surgery. Equine Surgery (4th edition). , 271-284 (2012).

- Mair, T. S., Smith, L. J. Survival and complication rates in 300 horses undergoing surgical treatment of colic. Part 2: Short-term complications. Equine Vet J. 37 (4), 303-309 (2005).

- Smith, L. J., Mellor, D. J., Marr, C. M., Reid, S. W., Mair, T. S. Incisional complications following exploratory celiotomy: does an abdominal bandage reduce the risk. Equine Vet J. 39 (3), 277-283 (2007).

- Klohnen, A. New perspectives in postoperative complications after abdominal surgery. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 25 (2), 341-350 (2009).

- Freeman, K. D., Southwood, L. L., Lane, J., Lindborg, S., Aceto, H. W. Post operative infection, pyrexia and perioperative antimicrobial drug use in surgical colic patients. Equine Vet J. 44 (4), 476-481 (2012).

- Birke-Sorensen, H. Evidence-based recommendations for negative pressure wound therapy: treatment variables (pressure levels, wound filler and contact layer)-steps towards an international consensus. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 64 (Suppl), S1-S16 (2011).

- Jordana-Garcia, M., Pint, E., Martens, A. The use of vacuum-assisted wound closure to enhance skin graft acceptance in a horse. Vlaams Diergeneeskundig Tijdschrift. 80 (5), 343-350 (2011).

- Gemeinhardt, K., Molnar, J. Vacuum-assisted closure for management of a traumatic neck wound in a horse. Equine Vet Edu. 17 (1), 27-33 (2005).

- Salciccia, A., Grulke, S. de la Rebière de Pouyade, G. La ténosynovite septique - 2e partie: traitement et pronostic. Le Nouveau Praticien Vétérinaire - Equine. 16 (56), 20-24 (2022).

- Gaus, M., Rohn, K., Roetting, A. K. Applicability and effect of a vacuum-assisted wound therapy after median laparotomy in horses. Pferdeheilkunde-Equine Medicine. 33 (6), 563-572 (2017).

- Bramlage, L. R., Richardson, D. W., Markel, M. D., von Salis, B., Fackelman, G. E., Auer, J. A., Nunamaker, D. M. Mandible, maxilla and skull. AO Principles of Equine Osteosynthesis. , 34-55 (2000).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved