Method Article

Laparoscopic Choledochal Cyst Excision and Roux-en-Y Choledochojejunostomy in Adults

* These authors contributed equally

In This Article

Summary

Choledochal cysts in adults are relatively rare, and few reports have detailed treatment options. Here, we present a case demonstrating laparoscopic resection of choledochal cysts and posterior colonic Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy in adults, offering an alternative for clinical management.

Abstract

Choledochal cysts (CCs), known as congenital choledochal dilatations, are more prevalent in Asia. The majority of patients with abdominal symptoms are diagnosed and treated during early childhood, which results in a lower prevalence of CCs in adults. The treatment of choice for CCs is complete cyst excision followed by choledochojejunostomy. Laparoscopic surgery is now more widely accepted than traditional open surgery due to its smaller incisions, faster recovery, and less postoperative pain. However, there are few reports on laparoscopic excision of CCs in adults. This article presents a protocol that describes and demonstrates the complete procedure for laparoscopic excision of a choledochal cyst and Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy. A 32-year-old woman diagnosed with a 2.5 cm by 3 cm CC underwent surgery using a laparoscopic approach with post-colonic anastomosis. The procedure lasted 290 min with an estimated blood loss of approximately 100 mL. A follow-up abdominal CT scan on the sixth postoperative day showed a satisfactory recovery, leading to her discharge on the ninth day. This study aims to demonstrate the feasibility and safety of laparoscopically assisted excision of CCs in adults. This procedure is expected to become the preferred surgical option for CCs in adults due to its minimal surgical trauma and rapid postoperative recovery.

Introduction

Choledochal cysts (CCs), also known as congenital choledochal dilatations, can be single or multiple and involve the intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile ducts. These cysts are most commonly found in Asia, where the incidence is approximately 100 times higher than in Europe and the United States, affecting about 1 in 1,000 individuals1. CCs are most commonly diagnosed in children2. However, the number of adult patients diagnosed with CCs has increased in recent years, particularly among young females, who are affected at a rate four times higher than males3. The etiology of CCs remains unclear, but it is widely accepted that the cause may be the reflux of pancreatic fluid into the common bile duct, which is caused by anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union (APBDU)4,5. CCs in adults do not have specific symptoms and often present with abdominal pain, jaundice, and fever, which are commonly due to the complications of cholangitis. In addition to cholangitis, other complications of CCs include gallstones, pancreatitis, bile duct stones, and cholangiocarcinoma6. Due to the risk of cholangiocarcinoma and other complications, the removal of choledochal cysts (CCs) is recommended2.

The Todani classification is the most commonly used clinical criterion for staging choledochal cysts (CCs). It categorizes CCs into five types, with 80% of adult lesions being type I cysts7. The treatment for type I biliary dilatation has evolved; it initially involved cyst-jejunostomy but has progressed to completely removing the cyst and reconstructing the bile duct. Previously, the treatment for type I choledochal cysts (CCs) was cyst enterostomy. However, this procedure was later found to be associated with long-term complications, including anastomotic stricture, recurrent cholangitis, and malignancy8. Open total cyst removal and biliary reconstruction are now common9 and have become the dominant surgical procedures for the treatment of choledochal cysts10. As a group with high morbidity, younger women demand more cosmetic outcomes from their surgeries, and this demand has led to the increased use of laparoscopy in the treatment of choledochal cysts11. Several studies have shown that laparoscopic CC resection is comparable in efficacy to open surgery but less invasive, perhaps making it a better option for choledochal cysts11,12,13.

This article presents a case of laparoscopic excision of a choledochal cyst (CC, Todani type I) and a Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy behind the colon in an adult. It describes the complete procedure of laparoscopic resection of the CC and the choledochal-jejunal Roux-en-Y anastomosis. After dissecting and excising the CC, the gallbladder was removed. Subsequently, the jejunal loop was prepared, and the gastrocolic ligament and transverse mesocolon were incised to create a channel for the jejunal loop. The jejunal loop was then brought up through this channel to the hepatoduodenal ligament for an end-to-side anastomosis with the common bile duct. The mesocolic aperture was subsequently closed. A side-to-side anastomosis of the jejunum was performed approximately 45 cm from the jejunal anastomotic stoma. After cleansing the abdominal cavity and ensuring hemostasis, the operation was concluded. This approach is effective, allows for rapid postoperative recovery, and preserves the anatomical position of the bowel, making it a preferred treatment option for CC (Todani type I).

Protocol

The study protocol was conducted in accordance with the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen People's Hospital, Second Medical College of Jinan University. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for this study and the subsequent surgery.

NOTE: A 36-year-old female patient presented with intermittent epigastric pain and was diagnosed with a choledochal cyst (CC), type I choledochal dilatation, using Magnetic Resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). No stones or other obstructions in the bile ducts were observed.

1. Preoperative workup

- Determine the cyst's location, size, and peripheral vascularity based on imaging studies and select the appropriate surgical approach (Figure 1).

- Use abdominal ultrasound for the initial assessment of patients. If the ultrasound suggests the presence of CCs, then perform further diagnostic tests, such as abdominal computed tomography (CT) and MRCP to confirm the diagnosis.

- Excluding contraindications to surgery.

- As this is a benign condition, focus the primary preoperative assessment on the patient's general condition, including liver, kidney, lung, and heart function, to ensure that the patient can tolerate the procedure.

- After normalizing the patient's liver function and once the inflammation has subsided, perform the procedure.

NOTE: In cases where there is secondary dilatation of the common bile duct due to gallstones or other causes, removal of the choledochal cyst is not necessary; instead, treatment of the primary disease takes precedence.

2. Anesthesia

- Conduct the operation under general anesthesia.

- Insert a central venous catheter (8Fr) preoperatively to administer intraoperative and postoperative medications.

- Insert a radial artery catheter (20 G) and leave it in place to monitor blood pressure intraoperatively in real time. To prevent intraoperative infection, administer 1.5 g of cefuroxime sodium intravenously 30 min before surgery.

NOTE: Anesthesiologists determine the anesthetic dosage for patients based on their height, weight, age, and other personal characteristics.

3. Surgical technique

- Operation setting

- Position the patient in a feet-down tilt position with legs split apart. The surgeon stands to the patient's left, while the first assistant and the camera operator are positioned to the right and between the patient's legs.

- Insert a 10 mm trocar under the patient's navel to create an observation hole. Establish a carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum and then insert four operative trocars under direct laparoscopic vision.

- Position two 12 mm trocars in the midclavicular line, equidistant from the xiphoid process to the umbilicus (place the upper trocar in the left midclavicular line and the lower trocar in the right).

- Position two 5 mm trocars in the anterior axillary line, also equidistant from the xiphoid process to the umbilicus (project the upper trocar to the right anterior axillary line and the lower trocar to the left) (Figure 2).

- Exploration phase

- Before the dissection, explore the abdominal and pelvic cavities in a counter-clockwise manner to check for other lesions, such as effusion, adhesions, or purulent discharge.

NOTE: Considering this is a benign condition, only a brief exploration of the abdominal and pelvic cavities was performed.

- Before the dissection, explore the abdominal and pelvic cavities in a counter-clockwise manner to check for other lesions, such as effusion, adhesions, or purulent discharge.

- Dissection phase

- Remove the gallbladder removal.

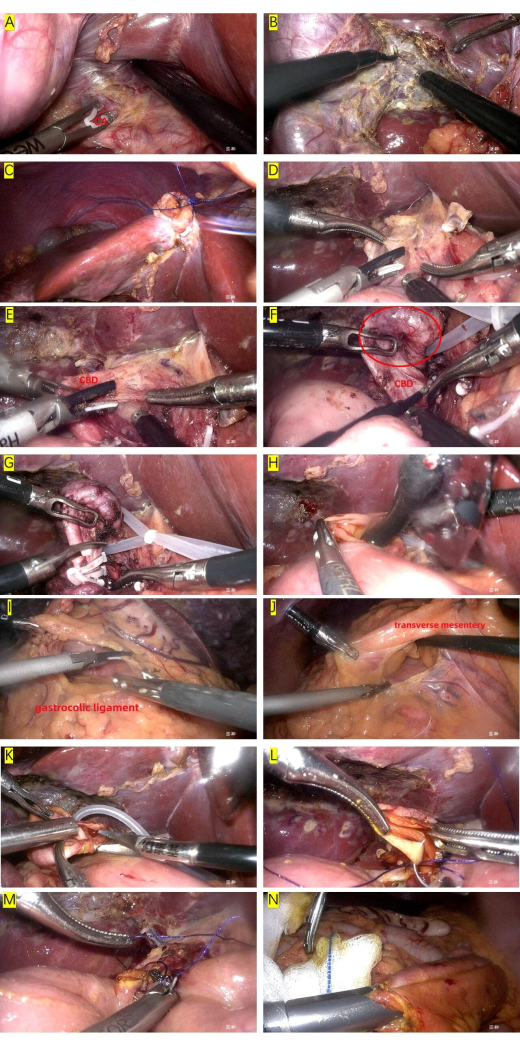

- Perform complete dissection of the structures within Calot's triangle, clamping and severing the cystic artery and cystic duct, followed by the complete removal of the gallbladder from the liver (Figure 3A,B).

- Suspend the round hepatic ligament.

- Clam and cut the round hepatic ligament, then suspend it from the anterior abdominal wall. Lift the liver upwards to visualize the surgical area fully (Figure 3C).

- Dissect the hepatoduodenal ligament and expose the common bile duct.

- Begin the dissection on the right side of the hepatoduodenal ligament to avoid damaging any vessels (Figure 3D). After exposing the common bile duct, free it from the left side to prevent damage to the hepatic veins and arteries (Figure 3E).

- Then, dissect the cyst distally towards the hepatic and pancreatic sides until it is reduced to the size of a normal duct (Figure 3F).

- If the cyst is so tightly adherent to the surrounding tissues that dissection is difficult, remove only the lining of the common bile duct, leaving the outer layer intact to prevent damage to the portal vein and hepatic artery located behind it.

- Separate the distal end of the CC.

- Clamp the common bile duct approximately 3 cm inferior to the CC, and then transect the common bile duct above the clamp (Figure 3G).

- Use two large hemo-locks (12 mm) to close the lower part of the common bile duct, preventing clip dislodgement or pancreatic reflux.

NOTE: In this patient, a healthy site about 3 cm inferior to the cyst was cut; the surgeon should clamp the common bile as more distally as they can.

- Cholangioscopic exploration

- Use choledochoscopy to check for the presence of bile duct stones or anatomical variations of the bile ducts (Figure 3H).

NOTE: Any stones in the bile ducts should be removed. Intraoperative cholangioscopy aims to identify bile duct variants to confirm the location of the severed common hepatic duct. Additionally, it combines the results of the preoperative Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) to clarify the anatomical variations of the biliopancreatic confluence, aiming to remove as much of the distal biliary cyst as possible while avoiding injury to the pancreatic duct.

- Use choledochoscopy to check for the presence of bile duct stones or anatomical variations of the bile ducts (Figure 3H).

- Remove the gallbladder removal.

- Reconstruction phase

- Establish the post-colonic intestinal channel.

- Seek two avascular areas in the transverse colonic mesentery and gastrocolic ligament, and then use an ultrasonic scalpel to make two openings, each about 3 cm in diameter, to serve as channels for the afferent loop (Figure 3I,J).

NOTE: To prevent postoperative intraperitoneal hernias, the size of the openings should correspond to the diameter of the patient's jejunum. If necessary, the diameter of the holes can be reduced by suturing following choledochojejunostomy.

- Seek two avascular areas in the transverse colonic mesentery and gastrocolic ligament, and then use an ultrasonic scalpel to make two openings, each about 3 cm in diameter, to serve as channels for the afferent loop (Figure 3I,J).

- Remove CC.

- Separate the cyst from the common bile duct, remove the specimen, and send it for pathological examination.

NOTE: In this case, the final results showed no evidence of malignancy (Figure 3K). - Combine the results of the preoperative MRCP to clarify the anatomical variations of the biliopancreatic confluence and remove as much of the distal biliary cyst as possible while avoiding injury to the pancreatic duct. Close the stump with two large hemo-locks.

NOTE: The type of APBDU in this patient is that the common bile duct joins the pancreatic duct outside the duodenal wall. In such cases, the common bile duct can be cut at the junction of the dilated and normal bile ducts, and the likelihood of injury to the pancreatic duct is generally low. Suppose there is a combination of pancreatic duct joins the common bile duct outside the duodenal intestinal wall or other complex types of confluence; the dilated bile duct is usually close to the pancreatic duct. In those cases, each ductal structure around the wall of the sac needs to be carefully identified to prevent damage to the pancreatic duct. If necessary, the pancreas can be identified by squeezing it and observing the presence of pancreatic fluid coming out of the opening in the sac wall to identify the pancreatic duct.

- Separate the cyst from the common bile duct, remove the specimen, and send it for pathological examination.

- Laparoscopic choledochojejunostomy.

- Incise the jejunum at approximately 10 cm from the Treitz ligament. Then, lift the transected lower limb upwards through the transverse colonic mesentery and gastrocolic ligament to the area of the common bile duct through the channel.

- Make a 1.5 cm incision at the jejunum with an ultrasonic scalpel and then anastomose it to the common bile duct. Use two 5-0 polydioxanone sutures (PDS) to anastomose the end-to-side and mucosa-to-mucosa. Close the posterior and anterior walls of the anastomosis consecutively (Figure 3L, M).

NOTE: To prevent anastomotic stricture, using interrupted sutures to close the anastomosis in patients with a common bile duct diameter of less than 8 mm is recommended. It is important to ensure a tension-free alignment of the tissues and good blood circulation in the tube wall; otherwise, anastomotic fistulae may easily form.

- Jejunojejunostomy

- Perform a jejunojejunostomy between the jejunum (located 40 cm distal to the jejunojejunal anastomotic stoma) and the transected upper limb using a side-to-side linear cutting stapler (Figure 3N). Subsequently, use 4-0 PDS sutures to reinforce the anastomosis to prevent leakage.

- Clean the abdominal cavity and place drains.

- Remove gauze from the abdominal cavity and ensure adequate hemostasis. Finally, place two 22F drains with side grooves, one in each anastomosis.

- Establish the post-colonic intestinal channel.

Results

The operation lasted 290 min with about 100 mL of blood loss. The patient's CC was entirely removed. The patient recovered well after surgery, showing no signs of postoperative pancreatic fistula or biliary fistula. The drainage fluid was clarified and decreased daily. A follow-up CT of the upper abdomen on the sixth postoperative indicated a good postoperative recovery (Figure 4). The drains were removed on the eighth postoperative day, and the patient was discharged on the ninth day. The patient has regular outpatient follow-ups after discharge and is currently experiencing no postoperative complications or discomfort.

Figure 1: MRCP images. The choledochal cyst is shown in red circles. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Surgical position setting and trocar placement. (A) 10 mm trocar for observation (B,C) 12 mm trocars for operation, (D,E) 5mm trocars for operation. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Phase of the surgery. (A,B) Gallbladder removal, CA: cystic artery. (C) Suspend the round hepatic ligament. (D) Dissect the hepatoduodenal ligament. (E) Expose the common bile duct, CBD: common bile duct. (F)Expose the choledochal cysts (shown in the red circle). (G) Separate the distal end of the choledochal cyst. (H) Cholangioscopic exploration. (I,J) Establish the post-colonic intestinal channel. (K) Excision of choledochal cyst. (L) Choledochojejunostomy: suture the posterior wall of the anastomosis. (M) Choledochojejunostomy: suture the anterior wall of the anastomosis. (N) Jejunojejunostomy. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4. Postoperative CT image in day 6. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| Postoperative details of the patient | |

| Duration of surgery | 290 min |

| Blood loss | 100 mL |

| Removal of drainage tube | 8th post-operative day |

| Day of discharge | 9th post-operative day |

| Cyst size | 2.5 cm ´ 3 cm |

| Pathological type | Choledochal cyst |

Table 1: Surgical outcomes and postoperative details of the patient.

Discussion

Choledochal cysts are prone to complications such as cholangitis, which can cause recurrent abdominal pain, jaundice, and fever; repeated inflammation may even lead to malignant transformations. Therefore, early diagnosis and complete cyst removal are necessary14. Abdominal ultrasound should be the first option when a choledochal cyst (CC) is suspected. If the ultrasound shows abnormal echoes in the area of the common bile duct, further imaging is warranted. Computed tomography (CT) is an important complementary test to visualize the location and size of cysts; enhanced CT can determine the vascular distribution around the lesion and assist in planning the surgical approach. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is a well-established noninvasive examination that uses heavily T2-weighted pulse sequences to depict the fluid-rich biliary system and has been widely used in the diagnosis of biliopancreatic diseases, including CCs15. MRCP can identify choledochal cysts (CCs) more clearly than CT, showing the location and morphology of the cysts and excluding other bile duct lesions. We recommend that patients with CCs undergo MRCP preoperatively.

The currently prevailing view on the etiology of choledochal cysts is that they result from an anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union (APBDU)2. This perspective suggests that the junction of the pancreatic and biliary ducts is located outside the duodenal wall. Consequently, the sphincter of Oddi does not functionally influence this junction, allowing pancreatobiliary reflux to occur, which can lead to various pathological conditions in the biliary tract4. In 1977, Todani classified choledochal cysts (CCs) into five types, a classification system that has been in use since then16. Type I cysts are the most prevalent, accounting for about 70% of all choledochal cysts (CCs). They present as cystic or fusiform dilatations of the extrahepatic bile ducts. Historically, the treatment for type I CCs entailed cyst enterostomy; however, this procedure was later found to be associated with long-term complications, including anastomotic stricture, recurrent cholangitis, and malignancy8. Excision of the entire cyst and restoration of biliary-enteric continuity constitutes the prevailing view. Cyst excision and hepaticojejunostomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis can treat Type I choledochal cysts (CCs). If the extent of choledochal dilatation involves the pancreatic head segment or even reaches the pancreatic ductal confluence, the risk of pancreaticoduodenectomy must be considered17. In cases where complete resection is difficult, the mucosa distal to the common bile duct may be stripped to protect the pancreaticobiliary junction18. Even electrocautery of cyst walls that cannot be completely removed and performing Roux-n-Y end-to-side hepaticojejunostomy reconstruction has been reported19.

Laparoscopic technology is rapidly transforming the treatment of diseases in abdominal surgery. Compared with traditional open surgery, laparoscopy offers the advantages of less trauma, better cosmesis, and faster postoperative recovery, but it also presents disadvantages such as limited space for instrument movement, lack of tactile feedback, and difficulty in bleeding control and exposure20. Surgeons may prefer the safer option of open surgery for areas of complex anatomy or procedures with cumbersome surgical procedures. However, with the advent of laparoscopic instruments such as the ultrasonic scalpel, articulating endoscopic linear cutter, and hem-o-lock, many surgical procedures such as hemostasis, anastomosis, and ligation have become much easier21. The difficulties in resectioning CCs are complete exposure and precise anastomosis22, which is precisely where laparoscopic technology excels. Laparoscopy can magnify the view and allow for more precise intraoperative manipulation, reducing the incidence of injury and adverse surgical complications19. Laparoscopic surgery for choledochal cysts has been attempted by some researchers with good results, but it has not yet been widely adopted11,12,13.

Here, we describe the procedure for laparoscopic excision of a choledochal cyst and Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy for Todani type I cysts. The key steps in this procedure are the stripping of the choledochal cyst and the bilioenteric anastomosis. Preoperative MRCP was combined with intraoperative cholangioscopy to clarify the presence and type of anatomical variant. In this patient, the type of anomalous confluence is where the bile duct joins the pancreatic duct outside the duodenum. In such cases, the common bile duct can be cut at the junction of the dilated and normal bile ducts, and the likelihood of injury to the pancreatic duct is generally low. Suppose there is a combination of pancreatic duct and bile duct confluence or other complex types of confluence; the dilated bile duct is usually close to the pancreatic duct. In those cases, each ductal structure around the wall of the sac needs to be carefully identified to prevent damage to the pancreatic duct. If necessary, the pancreas can be identified by squeezing it and observing the presence of pancreatic fluid coming out of the opening in the sac wall to identify the pancreatic duct23. If the cyst is so tightly adherent to the surrounding tissues that dissecting it is difficult, it is acceptable to remove only the cyst's lining, leaving the outer layer intact to prevent damage to the portal vein and hepatic artery located behind it19.

For bilioenteric anastomosis, it is crucial to ensure that there is no tension in the anastomosis and to avoid injury during suturing. Polydioxanone sutures (5-0) are more suitable for closing anastomoses because they are less traumatic to the surrounding tissues and have antimicrobial properties24. To prevent anastomotic stricture, we recommend using interrupted sutures to close the anastomosis in patients with a common bile duct diameter of less than 8 mm. For diameters greater than 8 mm, continuous sutures can be used for anastomosis. Skilled laparoscopic suturing is also a key factor in reducing collateral damage and ensuring proper anastomotic alignment. If the operation is found to be difficult intraoperatively, conversion to open surgery should be considered. Robot-assisted laparoscopic abdominal surgery offers additional advantages in suture manipulation and maybe a newer option for choledochal cysts25.

In conclusion, choledochal cystectomy is a relatively complex procedure that requires meticulous operation to ensure its safety and effectiveness. The total laparoscopic excision of CCs has the advantages of anatomical precision, less tissue injury, and rapid recovery. This procedure can be attempted as an alternative to open surgery in advanced medical centers.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Foundation of Shenzhen (Nos. JCYJ20220530152200001), Guangdong Medical Science and Technology Research Fund (Nos. B2023388) and Shenzhen Science and Technology Programme Project Fund (Nos.SGDX20230116092200001). We thank the anaesthesiologists and operating room nurses who assisted with the operation.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 5-0 Polydioxanone sutures | Ethicon Medical Technology Co. | W9733T | |

| Articulating Endoscopic Linear Cutter | Jinhuawai Medical Technology Co. | HWQM60A | |

| Harmonic | Ethicon Medical Technology Co. | HAR36 | |

| High frequency ablation of hemostatic electrodes | Shuyou Medical Equipment Co. | sy-vIIc(Q)-5 | |

| Ligature clips | Wedu Medical Equipment Co. | WD-JZ(S) | |

| Ligature clips | Wedu Medical Equipment Co. | WD-JZ(M) | |

| Linear Cutter universal loading unit | Jinhuawai Medical Technology Co. | HWQM60K | |

| Two-electrode voltage-clamp | Karl Storz Se & Co. | 38651ON |

References

- Ronnekleiv-Kelly, S. M., Soares, K. C., Ejaz, A., Pawlik, T. M. Management of choledochal cysts. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 32 (3), 225-231 (2016).

- Soares, K. C., et al. Choledochal cysts: Presentation, clinical differentiation, and management. J Am Coll Surg. 219 (6), 1167-1180 (2014).

- Xia, H. T., Yang, T., Liang, B., Zeng, J. P., Dong, J. H. Treatment and outcomes of adults with remnant intrapancreatic choledochal cysts. Surgery. 159 (2), 418-425 (2016).

- Cha, S. W., et al. Choledochal cyst and anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union in adults: Radiological spectrum and complications. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 32 (1), 17-22 (2008).

- Park, S. W., Koh, H., Oh, J. T., Han, S. J., Kim, S. Relationship between anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union and pathologic inflammation of bile duct in choledochal cyst. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 17 (3), 170-177 (2014).

- Saluja, S. S., Nayeem, M., Sharma, B. C., Bora, G., Mishra, P. K. Management of choledochal cysts and their complications. Arch Surg. 78 (3), 284-290 (2012).

- Abbas, H. M., Yassin, N. A., Ammori, B. J. Laparoscopic resection of type I choledochal cyst in an adult and roux-en-y hepaticojejunostomy: A case report and literature review. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 16 (6), 439-444 (2006).

- Xia, H. T., Dong, J. H., Yang, T., Liang, B., Zeng, J. P. Selection of the surgical approach for reoperation of adult choledochal cysts. J Gastrointest Surg. 19 (2), 290-297 (2015).

- Stringer, M. D. Laparoscopic management of choledochal cysts: Is a keyhole view missing the big picture. Pediatr Surg Int. 33 (6), 651-655 (2017).

- Ahmed, B., Sharma, P., Leaphart, C. L. Laparoscopic resection of choledochal cyst with roux-en-y hepaticojejunostomy: A case report and review of the literature. Surg Endosc. 31 (8), 3370-3375 (2016).

- Jang, J. Y., et al. Laparoscopic excision of a choledochal cyst in 82 consecutive patients. Surg Endosc. 27 (5), 1648-1652 (2012).

- Diao, M., Li, L., Cheng, W. Laparoscopic versus open roux-en-y hepatojejunostomy for children with choledochal cysts: Intermediate-term follow-up results. Surg Endosc. 25 (5), 1567-1573 (2011).

- Margonis, G. A., et al. Minimally invasive resection of choledochal cyst: A feasible and safe surgical option. J Gastrointest Surg. 19 (5), 858-865 (2015).

- Yuan, H., Dong, G., Zhang, N., Sun, X., Zhao, H. Minimally invasive strategy for type I choledochal cyst in adult: Combination of laparoscopy and choledochoscopy. Surg Endosc. 35 (3), 1093-1100 (2020).

- Bogveradze, N., et al. Is MRCP necessary to diagnose pancreas divisum. BMC Med Imaging. 19 (1), 33 (2019).

- Todani, T., Watanabe, Y., Narusue, M., Tabuchi, K., Okajima, K. Congenital bile duct cysts: Classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 134 (2), 263-269 (1977).

- Shao-Cheng, L., et al. Technical points of total laparoscopic choledochal cyst excision. Chin Med J (Engl). 126 (5), 884-887 (2013).

- Sastry, A. V., Abbadessa, B., Wayne, M. G., Steele, J. G., Cooperman, A. M. What is the incidence of biliary carcinoma in choledochal cysts, when do they develop, and how should it affect management. World J Surg. 39 (2), 487-492 (2015).

- Senthilnathan, P., et al. Laparoscopic management of choledochal cyst-technical modifications and outcome analysis. World J Surg. 39 (10), 2550-2556 (2015).

- Morise, Z., Wakabayashi, G. First quarter century of laparoscopic liver resection. World J Gastroenterol. 23 (20), 3581-3588 (2017).

- Zheng, M. H., Zhao, X. Next era of the thirty-year Chinese laparoscopic surgery: Past, present, and future. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 24 (8), 653-656 (2021).

- Yang, X. W., et al. Case-control study of the efficacy of retrogastric roux-en-y choledochojejunostomy. Oncotarget. 8 (46), 81226-81234 (2017).

- Biliary Surgery Group of the Chinese Medical Association Surgery Branch. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of bile duct dilatation (2017 edition). Chinese Journal of Digestive Surgery. 16 (08), 767-774 (2017).

- Gierek, M., et al. Absorbable sutures in general surgery - review, available materials, and optimum choices. Pol Przegl Chir. 90 (2), 34-37 (2018).

- Lee, H., et al. Comparison of surgical outcomes of intracorporeal hepaticojejunostomy in the excision of choledochal cysts using laparoscopic versus robot techniques. Ann Surg Treat Res. 94 (4), 190-195 (2018).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved