Abdominal Exam IV: Acute Abdominal Pain Assessment

Overview

Source: Joseph Donroe, MD, Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

Abdominal pain is a frequent presenting concern in both the emergency department and the office setting. Acute abdominal pain is defined as pain lasting less than seven days, while an acute abdomen refers to the abrupt onset of severe abdominal pain with features suggesting a surgically intervenable process. The differential diagnosis of acute abdominal pain is broad; thus, clinicians must have a systematic method of examination guided by a careful history, remembering that pathology outside of the abdomen can also cause abdominal pain, including pulmonary, cardiac, rectal, and genital disorders.

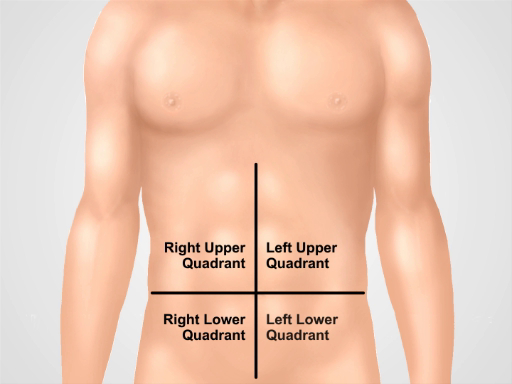

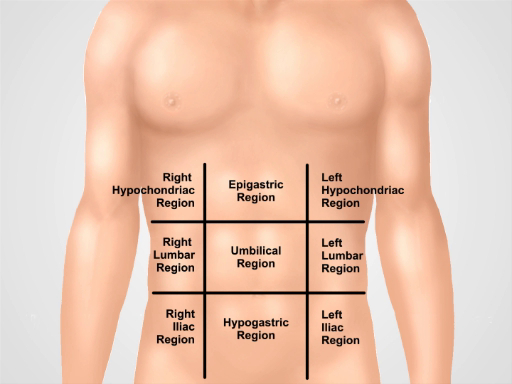

Terminology for describing the location of abdominal tenderness includes the right and left upper and lower quadrants, and the epigastric, umbilical, and hypogastric regions (Figures 1, 2). Thorough examination requires an organized approach involving inspection, auscultation, percussion, and palpation, with each maneuver performed purposefully and with a clear mental representation of the anatomy. Rather than palpating randomly across the abdomen, begin palpating remotely from the site of tenderness, moving systematically toward the tender region, and thinking about what lies below the fingers at each position. A helpful technique is to imagine a clock face with the xiphoid process at 12:00 and the pubic symphysis at 6:00 (Figure 3). When palpating at 8:00, there is skin, muscle, cecum, appendix, and ureters. Performing the exam in this fashion assists in clinical reasoning and minimizes the chance of missing pathology.

Figure 1. Four abdominal quadrants. Abdomen can be divided into four regions by two imaginary lines intersecting at umbilicus. Right upper quadrant (often designated as RUQ), left upper quadrant (LUQ), right lower quadrant (RLQ), and left lower quadrant (LLQ) are shown.

Figure 2. Nine abdominal regions. Midclavicular lines and subcostal and intertubercular planes separate abdomen into nine regions: epigastric region, right hypochondriac region, left hypochondriac region, umbilical region, right lumbar region, left lumbar region, hypogastric region, right inguinal region, and left inguinal region.

Figure 3. Visualizing a clock face over the abdomen for thinking about the underlying anatomy while performing the exam.

Procedure

1. Preparation

- Wash your hands and warm them prior to examining the patient.

- Have the patient put on a gown. An extra drape is necessary to cover the lower body.

- Begin with the patient lying supine on the exam table or bed.

2. Approach to acute abdominal pain

- Begin with a complete set of vital sign tests.

- After entering the room, immediately begin careful inspection. Patients with peritonitis may prefer to lie still with flexed hips and knees.

- Place a drape over the patient's lower body to the pubic symphysis and raise the gown to just below the breasts. Note abdominal distension, skin color, signs of poor perfusion, such as mottling, visible pulsation, or peristalsis, bulges, and scars.

- If the patient is alert, ask the patient to use one finger to point to the painful area. Ask the patient to cough (cough test) or gently bump the bed, which can localize the pain of peritonitis.

- Auscultate the left lower quadrant using the diaphragm with light pressure. Absent bowel sounds may indicate an ileus, while high pitch sounds suggest impending mechanical obstruction. Auscultation has the lowest yield of the diagnostic maneuvers for abdominal pain.

- Auscultate over any bulging areas to assess for herniated bowel.

- Proceed to use the head of the stethoscope to palpate the four quadrants with graduated pressure, while continuing to auscultate. Observe the patient's face for signs of distress, and feel the abdominal wall for rigidity.

- Percuss the abdomen, beginning with very light percussion (light percussion test) over the four quadrants. This can localize peritoneal pain and distinguish it from visceral pain.

- Continue with a moderate percussion stroke in the four quadrants, assessing for abnormal tympany, suggesting air (free air or gas-filled bowel), or dullness, suggesting fluid or mass.

- Ask the patient to flex the legs at the hips and knees.

- Begin palpation by placing the open right hand gently on the abdomen with fingers slightly spread. Use a light rocking motion as the patient breathes, feeling for abdominal wall rigidity. Feel each quadrant in this way, beginning farthest from the site of pain. Distracting the patient with conversation can serve to minimize voluntary guarding.

- Palpate again using moderate pressure with the finger pads (not the fingertips), in a clockwise fashion. In the middle of the clock face, palpate the aorta.

- Palpate bulges evoking suspicion of abdominal wall hernias, and attempt to reduce if present.

- In selected patients, particularly those with lower quadrant pain or suspicion of gastrointestinal bleed, perform a rectal examination.

- Perform a testicular exam on males with lower abdominal pain.

- Perform a pelvic exam on females with abdominal pain.

3. Special Maneuvers in Selected Patients with Abdominal Pain.

- Test for Murphy's sign in patients with right upper quadrant pain. Palpate in the midclavicular line, just below the liver edge.

- Ask the patient to take a deep breath while you palpate deeply. Pain accompanied by cessation of inspiration suggests acute cholecystitis.

- For right lower quadrant pain, the following maneuvers can be diagnostically helpful:

- Elicit Rovsing's sign by deep palpation of the left lower quadrant. Pain referred to the right lower quadrant suggests acute appendicitis.

- Perform the obturator sign by flexing the patient's right hip and knee to 90° and internally rotating the hip. Pain in the right lower quadrant suggests acute appendicitis or a pelvic abscess.

- Perform the psoas sign by having the patient flex the right thigh against the examiner's resisting hand. Lower abdominal pain suggests a retrocecal appendicitis or psoas abscess.To perform an alternate method of the psoas sign, place the patient in the left lateral decubitus position, and standing behind the patient, extend the patient's thigh.

- Perform the Carnett test to assess for abdominal wall pain, which can mimic intra-abdominal pathology and often goes undiagnosed. Identify the point of maximal pain in the supine patient, and palpate there with moderate pressure to elicit tenderness.

- Ask the patient to raise the shoulders off the bed as if doing a sit-up, thereby contracting the abdominal wall muscles. Increased pain suggests an abdominal wall pain, while improved pain suggests intraperitoneal pathology (now protected by the contracted rectus muscles).

- Assess for splenomegaly in patients with left upper quadrant pain or signs of portal hypertension.

- Assess for ascites in patients with a suggestive history.

- Assess for groin hernias: Symptomatic groin hernias may be present with groin pain, an unreducible bulge, or signs of intestinal obstruction, such as abdominal distension, pain, and vomiting. Assessment for groin hernias should be undertaken in selected patients with lower abdominal or groin complaints. Ask the patient to stand, as this is the preferred position to evaluate for groin hernias. Steps 3.6.1. - 3.6.4. can also be performed in the supine position if the patient is unable to stand, though easily reducible hernias may be missed in this position.

- Put on gloves, and ask the patient to lift the gown in the front. Inspect the area of the inguinal canal, femoral canal, and scrotum (males) for bulges on both sides.

- Identify the inguinal ligament extending from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle. The inguinal canal runs parallel to it, between the internal and external inguinal rings. The internal ring, and origin of indirect hernias, is just superior to the midpoint of the inguinal ligament. The external inguinal ring is slightly superior and lateral to the pubic tubercle. The inguinal triangle, and area of origin of direct hernias, is bounded by the inferior epigastric artery laterally, the inguinal ligament inferiorly, and the linea semilunaris medially. The femoral canal lies below the inguinal ligament just medial to the femoral vein and artery.

- Ask the patient to turn the head to the side, and cough or simply bear down, and continue to observe for new bulging or increased size of an existing bulge.

- Using the finger pads of the right hand to examine the right side, palpate over the femoral canal, and ask the patient to cough or bear down again to assess for femoral hernias. Femoral hernias are more common in women and more likely than inguinal hernias to incarcerate.

- Next, palpate over the right inguinal canal. Ask the patient to cough or bear down, then feel for any bulges. An expanding bulge felt toward the midpoint of the inguinal ligament is likely an indirect hernia. A bulge felt near the pubic tubercle is more likely a direct hernia.

- Auscultate over any bulges, noting the presence or absence of bowel sounds.

- In males, if a scrotal mass is observed, palpate it, and try to palpate above it to differentiate it from testicular pathology.

- If no mass is yet evident, use the index finger of the right hand, with the finger pad facing the patient, to palpate the right external inguinal ring and distal inguinal canal by placing the finger on the scrotum, just above the right testicle.

- Invaginate the scrotum, following the spermatic cord superiorly and in the direction of the inguinal canal until the fingertip is just past the external inguinal ring. The spermatic cord (males) and round ligament (females) travels through the inguinal canal.

- Ask the patient to cough or bear down. A bulge felt at the fingertip may be an indirect hernia, while one felt on the side of the finger may be a direct hernia. Of note, the physician's ability to distinguish between direct and indirect hernias on physical exam is imprecise.

- Repeat on the left side using the left hand.

- Attempt to gently reduce any suspected hernias, avoiding forceful reduction. Reduction is facilitated by having the patient lie down in the Trendelenburg position.

Application and Summary

A systematic approach to examining a patient with acute abdominal pain includes inspection, auscultation, percussion, and palpation. Special maneuvers to detect abdominal wall pain, appendicitis, cholecystitis, and hernias should be performed if there is suspicion for these processes.

The exam findings that are most useful for increasing the probability of disease include rigidity and percussion tenderness for general peritonitis; McBurney's point tenderness, positive Rovsing's sign, and positive psoas sign for appendicitis; positive Murphy's sign and right upper quadrant tenderness for cholecystitis; visible peristalsis, abdominal distension, and high pitched-hyperactive bowel sounds for small bowel obstruction.

Findings that decrease the probability of disease are a positive Carnett's sign and negative pain with cough for general peritonitis; absence of right lower quadrant tenderness for appendicitis; absent right upper quadrant tenderness for cholecystitis; normal bowel sounds and absence of abdominal distension for small bowel obstruction.

The yield of the abdominal exam is much better if the clinician elicits an effective history, performs careful inspection, and considers the relevant regional anatomy when percussing and palpating. The physician's relationship with their patient benefits from having a gentle approach to one who is already in pain and avoiding unnecessary maneuvers that may increase patient discomfort without providing new information, such as the traditional test for rebound tenderness, where the physician palpates deeply over the area of pain then briskly removes the palpating hand, asking if tenderness was worse with palpation or release. An effective history and physical exam allow for cost-effective utilization of diagnostic imaging and enhance clinical interpretation of imaging results, as well as enabling the triage of patients who may need urgent surgery.

Tags

Skip to...

Videos from this collection:

Now Playing

Abdominal Exam IV: Acute Abdominal Pain Assessment

Physical Examinations II

66.9K Views

Eye Exam

Physical Examinations II

76.5K Views

Ophthalmoscopic Examination

Physical Examinations II

67.2K Views

Ear Exam

Physical Examinations II

54.4K Views

Nose, Sinuses, Oral Cavity and Pharynx Exam

Physical Examinations II

65.2K Views

Thyroid Exam

Physical Examinations II

104.2K Views

Lymph Node Exam

Physical Examinations II

384.6K Views

Abdominal Exam I: Inspection and Auscultation

Physical Examinations II

201.8K Views

Abdominal Exam II: Percussion

Physical Examinations II

247.1K Views

Abdominal Exam III: Palpation

Physical Examinations II

138.1K Views

Male Rectal Exam

Physical Examinations II

113.6K Views

Comprehensive Breast Exam

Physical Examinations II

86.6K Views

Pelvic Exam I: Assessment of the External Genitalia

Physical Examinations II

303.6K Views

Pelvic Exam II: Speculum Exam

Physical Examinations II

149.3K Views

Pelvic Exam III: Bimanual and Rectovaginal Exam

Physical Examinations II

146.7K Views

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved