Method Article

Laparoscopic Common Bile Duct Exploration Followed by Primary Suture Using a Modified Bile Duct Incision

* These authors contributed equally

In This Article

Summary

Cholecystolithiasis with common bile duct stones is a common disease; however, traditional common bile duct exploration has its own limitations. We propose a modified micro incision for laparoscopic common bile duct exploration aimed at reducing complication rates.

Abstract

Cholecystolithiasis is a common clinical disease, and 10-15% of patients with cholecystolithiasis have common bile duct (CBD) stones. Laparoscopic CBD exploration (LCBDE) followed by primary closure has proven to be safe and cost-effective for treating CBD stones and is typically performed via transcystic and transductal approaches. However, traditional LCBDE with choledochotomy may lead to biliary stricture and leakage, and performing choledochoscopy in transcystic LCBDE may be challenging because of the narrow cystic duct. To reduce the incidence rate of biliary stricture and leakage and increase the success rate of choledochoscopy, we propose a modified technique for bile duct incision. We performed LCBDE via a micro longitudinal incision extended along the cystobiliary junction toward the CBD instead of the traditional anterior wall of the CBD or purely transverse transcystic incision. Our micro incision size on CBD only ranged from 5 to 10 mm according to the size of the CBD stones. Using this micro incision technique, which is less invasive, resulted in easier exploration of the CBD and preservation of the ductal wall integrity. This approach encourages surgeons to use primary closure and may be considered a viable alternative choice for patients with ductal stones in the future.

Introduction

Cholelithiasis is among the most common clinical diseases in general surgery, and 10%-15% of patients concurrently experience cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis1. Common bile duct (CBD) primary closure, a procedure typically performed after biliary exploration or removal of biliary stones involves direct closure of the CBD incision and is performed to maintain the normal anatomical structure and biliary flow2,3. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) + laparoscopic CBD exploration (LCBDE) is considered an effective treatment option for patients with both gallbladder and CBD stones4, and its safety and efficacy have been previously reported3,5. With the development of laparoscopic techniques and medical devices, surgeons can now perform LCBDE using different approaches, including the transcystic and transductal approaches. Furthermore, in the last decade, significant advances have been made with LCBDE with primary sutures, which is gradually replacing the T-tube drainage procedure6,7.

However, complications are unavoidable in LCBDE and are primarily related to CBD resection (biliary leakage and stenosis). Postoperative bile leakage and bile duct stenosis can occur due to insufficient suturing or inadequate closure of the CBD8; these complications may cause abdominal infection and liver function damage, which can significantly delay recovery, increase the length of hospital stay, and lead to higher morbidity and mortality rates. Hence, to reduce the incidence rate of bile leakage, some surgeons tend to use T-tube drainage after LCBDE. However, carrying a T-tube for several weeks is uncomfortable for the patients. Furthermore, biliary leakage may occur if the T-tube is displaced. Therefore, it is vital to choose the appropriate incision and drainage process.

A transcystic approach to CBD exploration has been proposed to avoid CBD damage and eliminate the subsequent need for a T tube9,10. Nevertheless, the transcystic procedure is sometimes limited to patients presenting with a dilated cystic duct and poses challenges when addressing large stones11,12. Hence, the generalization of transcystic LCBDE with primary closure is currently restricted13.

To minimize CBD damage and optimize the use of the cystic duct, we propose a modified micro incision starting from the cystobiliary junction to the CBD. This technique is deemed suitable for patients with a non-dilated cystic duct because the incision contains both the cystobiliary junction and CBD. Furthermore, the technique allows surgeons to perform cholangioscopy and the primary sutures after LCBDE more easily. Further, a shorter incision on the CBD means less damage to the CBD, which can lead to lower postoperative biliary leakage and stenosis rates.

Protocol

This protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Dongguan Tungwah Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients who underwent surgery.

1. Operating setting and anesthesia

- Position the patient in a supine position with the head elevated at 30°. Administer general anesthesia via a laryngeal mask or tracheal intubation.

- To follow this protocol, for induction of anesthesia, use Sufentanil 0.3-0.5 µg/kg intravenous injection for analgesia, Propofol 1.5-2.5 mg/kg intravenous injection for sedation and loss of consciousness, and Vecuronium 0.1 mg/kg intravenous injection for muscle relaxation before endotracheal intubation. Use Sevoflurane for maintenance of anesthesia: maintain an end-tidal concentration of 1-1.5 MAC. Administer a continuous infusion of Propofol at 4-8 mg/(kg·h) or aTarget-Controlled Infusion (TCI) to maintain a bispectral index value of 40-60.

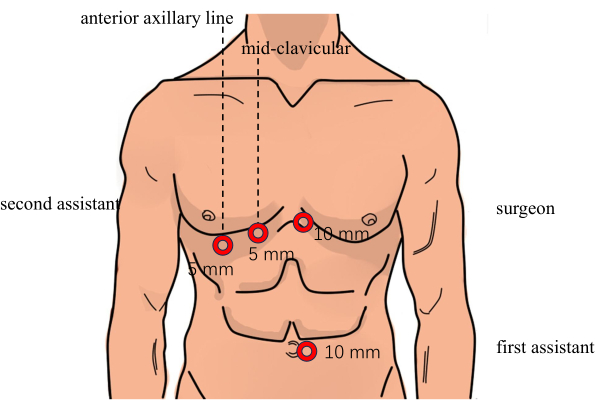

- Position the surgeon and second assistant to the left of the patient, at the head and foot, respectively. Position the first assistant to the right of the patient (Figure 1).

2. Surgical technique

- Insert the subumbilical trocar for the camera and establish the epigastric port (10 mm), right midclavicular port (5 mm), and right anterior axillary line port (5 mm) under direct vision. The distribution of these four trocars is shown in Figure 1.

- Position the patient in 20° reverse Trendelenburg with left lateral tilt for better visualization. Maintain pneumoperitoneum at 12 mmHg to create working space.

- Grasp the neck of the gallbladder or Hartmann's pouch with grasping forceps and apply traction in the right upper direction.

- Incise the serosa overlying the cystic duct, clear lymphatic tissue, and skeletonize the cystic artery.

- Ligate the cystic artery; then, completely dissect the cystic duct up to the cystobiliary junction.

- Utilize atraumatic graspers to engage the seromuscular layer of the proximal cystic duct, avoiding full-thickness compression. Apply anterolateral traction to achieve optimal cystic duct-CBD angulation. Maintain sufficient but not excessive tension to prevent ductal avulsion. Use locking clips in the distal cystic duct to temporarily prevent bile flow.

NOTE: To ligate the cystic artery, surgeons typically use surgical clips, sutures, or energy devices. We prefer sutures and energy devices to surgical clips because sometimes, clips in the Calot's triangle may obstruct surgeon's view and influence the next procedure. The optimal angle between the cystic duct and CBD does not have a fixed degree and usually 45-60° will be easier for a choledochoscope to enter the CBD. - Make a micro longitudinal incision extended along the cystobiliary junction toward CBD (Figure 2A) using electric hooks or scissors. Ensure that the incision size ranges from 5 mm to 10 mm according to the size of the stones.

NOTE: This incision is different from the traditional anterior wall of the CBD (Figure 2B) or transverse transcystic incision (Figure 2C). - Perform choledochoscopy using a 3 mm or 5 mm choledochoscope depending on the diameter of the cystic duct. Remove CBD stones in the basket; if impacted stones at the papilla level obstruct access to the basket, employ electrohydraulic lithotripsy to fragment the stones and collect them with the basket later.

- Reconfirm the clearance of CBD stones. Make sure the irrigation water flows smoothly through the CBD and the sphincter of Oddi works well.

- Close the incision primarily from the cystobiliary junction to the CBD anterior wall with a 5-0 Polydioxanone suture.

NOTE: We prefer continuous sutures to interrupted sutures owing to their time efficiency14. The process of bile duct exploration and primary suture is shown in Figure 3. - Close the proximal cystic duct using clips and cut the distal cystic duct. Remove the gallbladder completely.

- Confirm the absence of bile leakage and stenosis, then place a drainage tube near the CBD and pull it through the right anterior axillary line port.

Results

Between March 2022 and July 2024, LC + LCBDE was performed on 216 patients in our department. Transcystic LCBDE with micro incision followed by primary suture was performed on 42 patients (19.4%); traditional LCBDE + LC followed by primary suture was performed on 90 patients (41.6%); and 86 patients underwent LCBED + LC followed by T-tube drainage (40%).

We compared the modified transcystic micro incision group (42 patients) and traditional LCBDE + LC with primary suture group (90 patients). All values were expressed as the average ± SD. χ2 tests of significance were used for comparison and Student's t-test and Welch's t-test were used for categorical data. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Demographic features and clinical characteristics of patients in the modified transcystic micro incision and traditional LCBDE + LC with primary suture groups are shown in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were observed in age and sex distribution between the two groups. The patients in the LCBDE + LC group had higher grades of ASA classification compared with those in the modified incision group (P < 0.001). Compared to the modified micro incision group, higher numbers of patients in the LCBDE + LC group had elevated liver function tests, jaundice, and acute cholangitis before surgery.

There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of elevated liver function tests, jaundice, acute pancreatitis, and acute cholangitis before surgery. The average common bile duct diameter before surgery in the LCBDE + LC group was bigger than that in the modified micro incision group (P = 0.001). The size of the largest CBD stone and number of CBD stones of two groups did not differ significantly.

Operative findings and postoperative outcomes are listed in Table 2. The two groups showed no significant difference in operative time (P = 0.315). The blood loss during surgery (P = 0.007) and the postoperative stay (P = 0.024) was significantly lower in the modified micro incision group than that in the LCBDE + LC group. There was no significant difference in the incidence of complications in these two groups. Of 42 patients who underwent modified micro incision, only 3 (7.1%) patients had postoperative complications. One patient had a pulmonary infection and recovered later with the help of appropriate antibiotics. One patient developed postoperative acute pancreatitis and was cured by conservative therapy. One patient experienced postoperative biliary leakage, which was treated by endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage tube insertion and resolved without second surgery. None of the 42 patients developed biliary stenosis, and no residual stone or surgery-related deaths were noted. Of 90 patients who underwent traditional LCBED + LC, 5 (5.5%) patients had postoperative complications: one postoperative acute pancreatitis, two bile leakage, and two bile duct stenosis. The patient with acute pancreatitis and one of the patients with bile leakage were cured by conservative therapy. The other patient with bile leakage and two patients with bile duct stenosis were treated by endoscopic technique. All other patients in the traditional LCBDE + LC group recovered normally, and no residual stone or deaths were observed.

In general, the operative time and incidence of postoperative complications of the two groups were largely similar; nonetheless, the modified transcystic micro incision group exhibited markedly reduced operative hemorrhage and a shortened length of postoperative hospital stay, thereby underscoring the safety and minimal invasiveness of our modified transcystic micro incision.

Figure 1: Surgical position and trocar placement. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Three different incisions for bile duct exploration. (A) Micro longitudinal incision extended along the cystobiliary junction toward the common bile duct. (B) Common bile duct incision. (C) Transverse transcystic incision. Abbreviation: CBD = common bile duct. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Bile duct exploration and primary suture process. (A) Dissect the Calot's triangle. (B) Clip the cystic duct with Hem-o-lok. (C) Make a micro longitudinal incision extended along the cystobiliary junction toward the common bile duct. (D) Perform choledochoscopy using a choledochoscope. (E) Close the incision. (F) Finish the primary suture. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| Micro Transcystic incision (n=42) | LCBDE+LC (n=90) | P | |

| Age (years) | 49.93±17.69 | 53.74±16.55 | 0.23 |

| Sex (M:F) | 23:19 | 52:38:00 | 0.745 |

| ASAa [n (%)] | <0.001 | ||

| 1 | 21 (50) | 15 (16.7) | |

| 2 | 17 (40.5) | 55 (61.1) | |

| 3 | 4 (9.5) | 20 (22.2) | |

| Elevated liver function test [n (%)] | 36 (85.7) | 77 (85.5) | 0.981 |

| Jaundice [n (%)] | 29 (69) | 66 (73.3) | 0.611 |

| Acute cholangitis [n (%)] | 30 (71.4) | 64 (71.1) | 0.97 |

| Acute pancreatitis [n (%)] | 1 (2.3) | 3 (3.3) | 0.767 |

| CBD diameter (cm) | 1.30±0.27 | 1.59±0.52 | 0.001 |

| Size of the largest CBD stone (cm) | 1.07±0.23 | 1.21±0.46 | 0.088 |

| Number of CBD stones | 2.31±0.86 | 2.62±1.51 | 0.217 |

Table 1: Demographic features and clinical characteristics of patients. aASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; CBD = common bile duct.

| Micro Transcystic incision (n=42) | LCBDE+LC (n=90) | P | |

| Operative time (min) | 103.71±29.63 | 112.96±49.72 | 0.315 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 23.60±21.07 | 47.28±49.25 | 0.007 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (day) | 6.7±2.0 | 7.7±2.1 | 0.024 |

| Postoperative complication [n (%)] | |||

| Bile leakage | 1(2.3) | 2(2.2) | 0.955 |

| Bile duct stenosis | 2(2.2) | 0.322 | |

| Pancreatitis | 1(2.3) | 1(1.1) | 0.579 |

| Bleeding | 1 | ||

| Infection | 1(2.3) | 0.143 | |

| Residual stones | 1 |

Table 2: Operative findings and postoperative outcomes.

Supplemental Table S1: Perioperative data of traditional and modified incision LCBDE patients. Please click here to download this File.

Discussion

Currently, the transcystic LCBDE followed by primary closure is deemed the least invasive procedure and has the advantages of preserving the integrity of the major ductal wall and avoiding routine drainage of the CBD, which helps decrease the incidence rate of surgery-related complications (leakage and stenosis)15. In some cases, small-caliber choledochoscope may be the only option when the cystic duct is narrow, which can increase the incidence of residual stones and the rate of secondary surgeries for stone removal. However, if the incision is performed only in the cystic duct, it relies on the dilation of the cystic duct and extracting large CBD stones is difficult. Our team proposes performing the LCBDE by making a micro longitudinal incision extended along the cystobiliary junction toward the CBD instead of making a transverse cystic duct incision. The size of the incision typically ranges from 5 mm to 10 mm. Although this modified incision still involves the CBD, the length of incision on CBD is remarkably shorter than that adopted in choledochoscopy16, which can lead to lower biliary leakage and stenosis rates. Thanks to the usage of partial common bile duct, we could insert a large caliber choledochoscope (5 mm) through this incision regardless of whether the cystic duct is narrow or not. Therefore, our technique will not increase the incidence of residual stones and secondary surgeries for stone removal.

In fact, the technique of performing a longitudinal incision of the cystic duct for transcystic common bile duct stone removal is not a new approach. This method has been widely adopted by many institutions for over a decade. But what is most unique for our protocol is that the length of our micro incision is relatively shorter than previous studies. The incision size in our study ranges only from 5 mm to 10 mm according to the size of the stones, while the length of previous studies is approximately 20 mm. Moreover, some investigators have proposed a V-shaped incision16 and the length of V-shaped incision can even reach 30 mm. The shorter incision on the CBD means less damage to the CBD, which can lead to lower postoperative biliary leakage and stenosis rate.

Our study showed that the incidence rate of biliary leakage between the modified micro incision group and the traditional LCBDE + LC group was not statistically different (P = 0.955) and no biliary stenosis patient was observed in the modified micro incision group. This approach improves applicability to a broader population, including those with non-dilated cystic ducts. Furthermore, a balloon catheter was no longer needed, rendering the process both time-saving and cost-effective. Finally, suturing was easy because the incision was relatively small and short.

However, this protocol has several limitations. First, visualizing the common bile duct above confluence (upper common bile duct and hepatic bile duct) using choledochoscopy through a transcystic approach is technically challenging17. Although there was no case of residual stones in this study, we admit that the restriction in exploring the intrahepatic bile can lead to a higher risk of residual stones. Thus, our protocol is not suitable for patients with upstream biliary stones before surgery. Second, cutting the cystic duct becomes difficult in the presence of anatomical variations, such as severe angulation of the cystic duct to the left side of the CBD or a very low-lying origin of the cystic duct. Therefore, abdominal enhanced CT and MRCP should be taken for each patient before the surgery to evaluate the situation of biliary tract. Furthermore, intraoperative cholangiography could be performed if necessary. When patients are confirmed to have complex anatomic variants of the biliary tract, it would be better to undergo traditional LCBDE or open common bile duct exploration instead of our protocol. Third, there is a learning curve associated with the transcystic LCBDE and primary suture18,19. Transcystic LCBDE is technically more challenging than choledochotomy. Therefore, this procedure requires extensive anatomical knowledge and proficient suturing skills, rendering it difficult to perform this protocol at relatively lower-level centers. Fourth, attempting to perform a primary closure of the biliary tract in a patient with severe biliary infection may result in bile leakage, since bile leakage are associated with both the degree of tissue inflammation and inadequate closure of the incision. To reduce the complication rate and avoid operation failure, this protocol is not advisable for those patients with significant inflammation in the bile ducts. Hence, the infection status of each patient should be carefully evaluated before surgery.

Additionally, there are contingency plans for the failure of this protocol, which include the T-tube placement plan. If this protocol is utilized, since the previous incision of our protocol is too short (only 5-10 mm), we can extend the CBD incision to 15-20 mm to suit the T-tube. After placement of T-tube, we can suture cystic duct and common bile duct. Furthermore, as the sample size of the study was small, a larger number of cases should be studied in the future to strengthen the validity of the results. In summary, transcystic LCBDE, followed by primary suturing through a micro-longitudinal incision extended along the cystobiliary junction toward the CBD, is feasible for the treatment of CBD stones. However, further studies are needed to optimize this protocol to meet clinical needs and decrease surgery-related complications.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to our colleagues in the operating room.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Drainage tube (5 mm x 1100 mm) | Jiangsu Yangtze River | for draining fluid accumulations and blood | |

| Electronic choledochoscope | OLYMPUS | for bile duct exploration | |

| Electrosurgical Unit | Shanghai Hutong | for cutting and coagulating tissues | |

| Hem-o-lok | Teleflex | for the ligation and anastomosis of blood vessels and tissues | |

| Insuffator for laparoscopy | OLYMPUS | for insufflating carbon dioxide gas | |

| Laparoscope | STORZ | for laparoscopic surgery | |

| Laparoscopic Dissecting Forceps | Richard Wolf | for dissecting and grasping tissue | |

| Laparoscopic Grasping Forceps | Richard Wolf | for clamping tissue | |

| Laparoscopic Needle Holder | Kanger | for grasping and manipulating suturing needles | |

| Laparoscopic Scissors | Richard Wolf | for cutting various tissues | |

| Polydioxanone suture | Johnson & Johnson | for incision suturing | |

| Propofol | FRESENIUS KABI | for anaesthesia | |

| Screen | SONY | for showing images | |

| Sevoflurane | Jiangsu Hengrui | for anaesthesia | |

| SPSS ver22.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) | IBM | for data management, statistical analysis, graphical presentation, and predictive analytics | |

| Sufentanil | Eurocept BV | for anaesthesia | |

| Trocar (10 mm x 100 mm and 5 mm x 100 mm) | Unimicro | for puncturing the abdominal wall | |

| Vecuronium | Zhejiang Xianju | for anaesthesia |

References

- Cianci, P. Restini, E. Management of cholelithiasis with choledocholithiasis: Endoscopic and surgical approaches. World J Gastroenterol. 27 (28), 4536-4554 (2021).

- Fan, L. et al. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration with primary closure could be safely performed among elderly patients with choledocholithiasis. BMC Geriatr. 23 (1), 486 (2023).

- Wang, Y. et al. Efficacy and safety of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration via choledochotomy with primary closure for the management of acute cholangitis caused by common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc. 36 (7), 4869-4877 (2022).

- Zhang, W. J. et al. Treatment of gallbladder stone with common bile duct stones in the laparoscopic era. BMC Surg. 15, 7 (2015).

- Tinoco, R., Tinoco, A., El-Kadre, L., Peres, L., Sueth, D. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. Ann Surg. 247 (4), 674-679 (2008).

- Gurusamy, K. S., Koti, R., Davidson, B. R. T-tube drainage versus primary closure after laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (6), Cd005641 (2013).

- Zhang, W. J. et al. Laparoscopic exploration of common bile duct with primary closure versus t-tube drainage: A randomized clinical trial. J Surg Res. 157 (1), e1-5 (2009).

- Rendell, V. R. Pauli, E. M. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. JAMA Surg. 158 (7), 766-767 (2023).

- Fang, L. et al. Laparoscopic transcystic common bile duct exploration: Surgical indications and procedure strategies. Surg Endosc. 32 (12), 4742-4748 (2018).

- Memon, M. A., Hassaballa, H., Memon, M. I. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: The past, the present, and the future. Am J Surg. 179 (4), 309-315 (2000).

- Pang, L., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Kong, J. Transcystic versus traditional laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: Its advantages and a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 32 (11), 4363-4376 (2018).

- Hajibandeh, S. et al. Laparoscopic transcystic versus transductal common bile duct exploration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg. 43 (8), 1935-1948 (2019).

- Huang, J. et al. Laparoscopic transcystic common bile duct exploration: 8-year experience at a single institution. J Gastrointest Surg. 27 (3), 555-564 (2023).

- Wu, D. et al. Primary suture of the common bile duct: Continuous or interrupted? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 32 (4), 390-394 (2022).

- Navaratne, L. Martinez Isla, A. Transductal versus transcystic laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: An institutional review of over four hundred cases. Surg Endosc. 35 (1), 437-448 (2021).

- Kim, E. Y., Lee, S. H., Lee, J. S., Hong, T. H. Laparoscopic cbd exploration using a v-shaped choledochotomy. BMC Surg. 15 62 (2015).

- Chen, D., Zhu, A., Zhang, Z. Laparoscopic transcystic choledochotomy with primary suture for choledocholith. Jsls. 19 (1), e2014.00057 (2015).

- Zhu, H. et al. Learning curve for performing choledochotomy bile duct exploration with primary closure after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 32 (10), 4263-4270 (2018).

- Chuang, S. H., Hung, M. C., Huang, S. W., Chou, D. A., Wu, H. S. Single-incision laparoscopic common bile duct exploration in 101 consecutive patients: Choledochotomy, transcystic, and transfistulous approaches. Surg Endosc. 32 (1), 485-497 (2018).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionExplore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved