Method Article

Evaluation of Fatty Acid Oxidation in Cultured Bone Cells

In This Article

Summary

The present protocol describes an assay to assess the capacity for fatty acid oxidation in cultures of primary bone cells or relevant cell lines.

Abstract

Bone formation by differentiating osteoblasts is expected to require significant energetic input as these specialized cells must synthesize large extracellular matrix proteins that compose bone tissue and then concentrate the ions necessary for its mineralization. Data on the metabolic requirements of bone formation are emerging rapidly. While much remains to be learned, it is expected that derangements in the intermediary metabolism contribute to skeletal disease. Here, a protocol is outlined to assess the capacity of osteoblastic cells to oxidize 14C-labeled fatty acids to 14CO2 and acid-soluble metabolites. Fatty acids represent a rich-energy reserve that can be taken up from the circulation after feeding or after their liberation from adipose tissue stores. The assay, performed in T-25 tissue culture flasks, is helpful for the study of gene gain or loss-of-function on fatty acid utilization and the effect of anabolic signals in the form of growth factors or morphogens necessary for the maintenance of bone mass. Details on the ability to adapt the protocol to assess the oxidation of glucose or amino acids like glutamine are also provided.

Introduction

The osteoblast, derived from progenitor cells present in the bone marrow and the periosteum, is responsible for synthesizing and secretion of the mineralized, collagen-rich matrix that composes bone tissue. To fulfill this energetically expensive endeavor and contribute to the lifelong maintenance of skeletal integrity, these specialized cells maintain an abundant rough endoplasmic reticulum essential for synthesizing extracellular matrix proteins1,2 and numerous high membrane-potential mitochondria to harvest the requisite chemical energy from fuel substrates3,4. The importance of this latter function is exemplified by the cessation of bone growth and the development of osteopenia5,6 associated with energy deficits as in caloric restriction. The identity of the osteoblast's preferred fuel source and the data on the metabolic requirements of the osteoblast during differentiation or in response to anabolic signaling are emerging7,8.

Long-chain fatty acids represent a rich supply of chemical energy present in serum and released from adipose tissue in response to reduced caloric intake or heightened energy expenditure. After traversing the cell membrane and ligating to Coenzyme A to increase solubility, fatty acyl-CoAs are shuttled into the mitochondrial matrix by the dual carnitine palmitoyltransferase enzymes on the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes and carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase7. Within the mitochondrial matrix, the β-oxidation machinery chain shortens acyl-CoA in a 4-step process that generates acetyl-CoA that enters the TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle) and reducing equivalents. Catabolism of palmitate (C16), the most common fatty acids in animals, via this pathway yields ~131 ATP, substantially more than the ~38 ATP generated by glucose oxidation7.

Tracing studies using radiolabeled lipids indicated that bone takes up a significant fraction of circulating lipids9,10, while genetic ablation of enzymes critical to lipid catabolism leads to a reduction in osteoblast activity and bone loss9,11. The protocol presented here uses a 14C-labeled fatty acid to evaluate the capacity of cultured osteoblasts to fully metabolize fatty acids to CO2 or acid-soluble metabolites, which represent intermediate steps in the oxidation process. While the use of radioactivity is required, the method is straightforward, requires limited investment, and is adaptable for the benefit of other radiolabeled metabolites and cell types.

Protocol

This protocol uses the conversion of [1-14C]-oleic acid to 14CO2 as an indicator of fatty acid oxidation capacity. The local Radiation Safety office approved the protocol for using radioactive materials before initiating the experiments. All radiation procedures were performed behind a plexiglass shield using appropriate personal protective equipment. Local Animal Care and Use Committee approved the protocol prior to using primary cells.

1. Fatty acid oxidation in cultured osteoblasts

- Sub-culture the primary calvarial osteoblasts12 or an osteoblastic cell line like Mc3t3-E1, and plate in T-25 flasks (5 x 105 cells/flask) in α-MEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 0.1 μg/mL of streptomycin.

- Seed 3-4 flasks for each treatment group (i.e., control and gene knockout or vehicle and pharmacological treatment) for use in the experiment. Seed additional 1-2 flasks for each treatment group to normalize to cell number or protein concentrations. Incubate the culture flasks in a humidified cell culture incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

- Culture the cells for 2-3 days until the flasks become confluent. Induce the confluent cultures to differentiate by adding 50 µg/mL of Ascorbic acid and 10 mM of β-glycerol phosphate (see Table of Materials) to the culture media and continue culture for up to 14 additional days.

NOTE: Serum starvation (adding 0.5%-1% FBS) overnight is necessary if growth factor treatments are planned. Lowering the percentage of FBS limits the amount of non-radiolabeled lipids in the culture and allows the maximal effect of exogenous growth factors. If the effects of hormones are to be tested, charcoal-stripped FBS is used. - Prepare the filter paper, 15 mm x 30 mm rubber sleeve stoppers, and polypropylene center wells (see Table of Materials) the day before the experiment.

- Fold a 1 cm x 10 cm strip of filter paper in the shape of a fan and place it in the bucket of the polypropylene center well. Press the arm of the polypropylene center well through the center of the rubber sleeve stopper and lower the polypropylene center well into the T-25 flask. Then seal the flask with the sleeve stopper (Figure 1).

NOTE: It may be necessary to adjust the placement of the polypropylene center well to ensure it does not come in contact with the culture medium. During the experiment, the polypropylene center well prevents the filter paper from touching the labeling medium and allows for the collection of 14CO2.

- Fold a 1 cm x 10 cm strip of filter paper in the shape of a fan and place it in the bucket of the polypropylene center well. Press the arm of the polypropylene center well through the center of the rubber sleeve stopper and lower the polypropylene center well into the T-25 flask. Then seal the flask with the sleeve stopper (Figure 1).

- On the day of the experiment, conjugate [1-14C]-oleic acid to bovine serum albumin (BSA) by mixing 20% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline (5 μL per flask) with 0.1 μCi/mL of [1-14C]-oleic acid (0.6 μL/flask) in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Then place the tube in a 50 mL conical tube and incubate at 37 °C for 30 min with gentle shaking. Prepare 1-2 extra flasks for oleic Acid-BSA conjugates to account for pipetting error.

- Remove the culture medium from the tissue culture flask and replace it with 1.5 mL of fresh serum starvation media (step 1.2).

- For each flask, combine 5.6 μL of oleic Acid-BSA solution (step 1.4) with 2 μL of 100 mM carnitine solution and 1 mL of culture media to produce a labeling solution. Add the labeling solution to the culture flasks. Keep the excess solution to read the total counts of activity added to the assay.

NOTE: The labeling solution is not added to the extra flasks intended to quantify cellular number or protein concentration. - Lower the polypropylene center wells containing the filter paper in the flask and then cap it with the rubber stopper.

NOTE: It is critical that the polypropylene center well must not contact the culture medium. This will lead to cross-contamination of the filter paper with radiolabeled fatty acid instead of CO2. - Incubate the cell cultures for 3 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

- To collect 14CO2, inject 150 μL of 1 N NaOH into the polypropylene center well to wet the filter paper and 200 μL of 1 M perchloric acid into the culture medium. Inject the NaOH and perchloric acid by pushing a needle through the rubber stopper.

NOTE: The rubber stopper should not be removed from the flask. This may cause 14CO2 to escape. For the ease of the injection, keep the flask in the upright position and then return to the culture position after the injections are complete. - Incubate the flasks at 55 °C for 1 h.

- Open the flasks after cooling them in the cell culture hood. Remove the filter papers from the polypropylene center wells with tweezers and place them in 3-4 mL of scintillation liquid (see Table of Materials) in a scintillation vial.

NOTE: 100 μL of excess labeling solution is added to 3-4 mL of the scintillation liquid to measure total counts of activity. 100 μL of basal culture media (without [1-14C]-oleic acid) is added to 3-4 mL of scintillation liquid to measure background activity. - After incubating at room temperature for 1 h or overnight, measure the radioactivity in counts per minute (cpm) using a scintillation counter (see Table of Materials).

- To normalize the cpm results, isolate the protein extracts from the unlabeled T-25 flasks for each culture condition. Wash with 5 mL phosphate-buffered saline, add 1 mL RIPA cell lysis buffer to each flask, and scrape the cell surface with a cell scraper.

- Transfer the RIPA buffer to a microcentrifuge tube with a pipette and centrifuge at 19,000 x g for 20 min at 4 °C. Transfer the supernatant with a pipette to a fresh microcentrifuge tube and determine the protein concentration according to BCA assay protocol (see Table of Materials).

- Divide the raw cpm reads from the scintillation counter by the protein concentration to obtain the normalized cpm of 14CO2 produced (Table 1).

- Follow local requirements to dispose of the scintillation vials, cell culture materials, medium, syringes, etc. Decontaminate the work surfaces and perform radioactivity wipe tests following local requirements.

2. Acid-soluble metabolite collection

NOTE: The 3 h incubation period used in step 1.8 above may not be sufficient time to oxidize all the [1-14C] fully-oleic acid taken up by cells to CO2. Flux in the fatty acid oxidation pathway can also be assessed by measuring radioactivity in the acid-soluble fraction.

- Collect 1 mL of the acidified media from each treated T-25 flask and transfer it to a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 60 μL of 20% BSA and 100 μL of 16 M perchloric acid.

- Vortex and incubate overnight at 4 °C.

- Next, vortex and centrifuge at 20,000 x g for 30 min at 4 °C.

- Add 200 μL of the supernatant to the scintillation liquid and measure activity (step 1.12).

- Normalize the reads to protein concentration or DNA measurements (step 1.13.1).

3. Measurement of glucose oxidation or amino acid oxidation

- Replace 14C-labeled oleic acid with 14C-labeled glucose or 14C-labeled amino acids to measure oxidation of these fuel molecules.

- Prepare osteoblast cultures according to steps 1.1-1.2.

- To initiate the experiment, remove the culture medium from the tissue culture flask and replace it with 1.5 mL of fresh serum starvation media.

- Prepare a labeling solution of 0.6 μCi of 14C-labeled glucose or 14C-labeled amino acids in 1 mL of starvation media and add to flasks.

- Perform steps 1.6-1.13.

Results

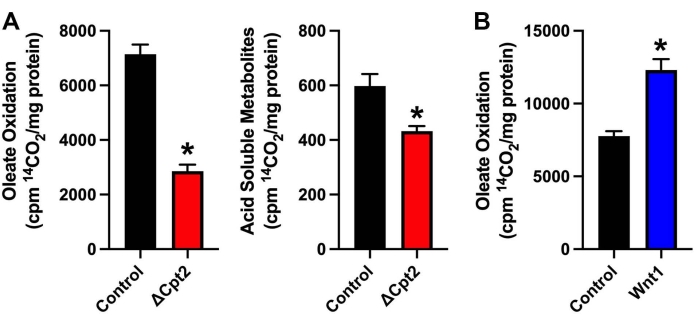

Enzymatic activity of both carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 (Cpt1) and carnitine palmitoyltransferase-2 (Cpt2) are required for mitochondrial long-chain fatty acid oxidation. Cpt1 is the rate-limiting enzyme in the metabolic pathway, but three isoforms (Cpt-1a, Cpt-1b, and Cpt-1c) are encoded in mammalian genomes, and the genetic disruption of one isoform can lead to compensation upregulation of another isoform13. By contrast, Cpt2 is encoded by a single gene. In the experiment illustrated in Figure 2A, genetic ablation of Cpt2 results in a ~60% reduction in the oxidation of [1-14C]-oleic acid to 14CO2 and a ~27% decrease in the labeling of acid-soluble metabolites relative to controls in cultures of primary mouse calvarial osteoblasts that have been differentiated for 7 days. The remaining capacity to oxidize oleic acid to CO2 in the mutant osteoblasts is expected to be due to peroxisomal oxidation or ω-oxidation. The smaller relative decrease in acid-soluble metabolite labeling in the mutant cells is likely the result of normal or elevated fatty acid uptake. Indeed, the abundance of fatty acyl-carnitines increases in osteoblast deficient for Cpt29. In the experiment illustrated in Figure 2B, fatty acid oxidation was assessed in wild-type osteoblasts and osteoblasts that overexpress Wnt19. Since the activation of Wnt signaling was induced via a genetic manipulation rather than via treatment with an exogenous ligand (which would require an incubation period after treatment), the assay was completed in a single day.

Figure 1: Assembly of the polypropylene center well and sleeve stopper. (A) A strip of Whatman filter paper is cut with a width just short of the depth of the polypropylene center well (~1 cm). (B) The filter paper is fanned or rolled and then inserted into the polypropylene center well. (C) The arm of the polypropylene center well is pushed through the rubber sleeve stopper. Avoid tearing a hole in the stopper, which could allow CO2 escape. (D) After adding the labeling mixture, the polypropylene center well and sleeve stopper are used to seal the T-25 flask. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Fatty acid oxidation in primary mouse osteoblasts. (A) Oxidation of [1-14C]-oleic acid to 14CO2 (left panel) or soluble acid metabolites (right panel) in cultures of control osteoblasts or osteoblasts deficient for carnitine palmitoyltransferase-2 (ΔCpt2). (B) Graphical representation of the osteoblasts that overexpress Wnt1 exhibit an increased ability to oxidation [1-14C]-oleic acid to 14CO2. Results are shown as the counts per minute (cpm) normalized to mg of protein and mean ± standard error. *p < 0.05. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| Sample | cpm 14CO2 | Protein (mg) | cpm/mg protein |

| Control_1 | 9243 | 1.34311224 | 6881.777803 |

| Control_2 | 7925 | 5900.474855 | |

| Control_3 | 10983 | 8177.276383 | |

| Control_4 | 9643 | 7179.593568 | |

| Control_5 | 13270 | 9880.038023 | |

| Control_6 | 10293 | 7663.544187 | |

| Control_7 | 10539 | 7846.700883 | |

| Control_8 | 10131 | 7542.928802 | |

| Wnt1_1 | 12961 | 1.08545918 | 11940.56878 |

| Wnt1_2 | 11853 | 10919.80262 | |

| Wnt1_3 | 16203 | 14927.3232 | |

| Wnt1_4 | 13629 | 12555.97654 | |

| Wnt1_5 | 13681 | 12603.88253 | |

| Wnt1_6 | 15803 | 14558.81556 | |

| Wnt1_7 | 13845 | 12754.97067 | |

| Wnt1_8 | 8855 | 8157.837865 |

Table 1: Raw cpm data normalized to protein concentration. Raw cpm counts of 14CO2 are normalized by dividing by the amount of protein extracted from the unlabeled flasks.

Discussion

The procedure described above allows for the direct assessment of fatty acid oxidation as the measured outputs are 14CO2 collected on the NaOH soaked filter paper and acid-soluble metabolites collected after the acidification of the culture with perchloric acid. Commercially available assay kits that use fluorescently labeled lipid molecules or lipid analogs can measure lipid uptake, but they do not determine catabolism for energy generation. Other measures of catabolism, such as 13C-metabolic flux14, require specialized analysis equipment. This assay is sensitive and relatively rapid as it can be completed in a single day if only the levels of 14CO2 are needed (Figure 2). Alternatively, the filter paper can be incubated in scintillation liquid overnight and read simultaneously as the acid-soluble metabolites if the determination of both outcomes is desired. If a negative control is needed, investigators can pretreat cells with etomoxir, an irreversible inhibitor of carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1. However, interpretation of these data requires care since etomoxir also inhibits adenine nucleotide translocase and components of the electron transport chain15,16. In osteoblasts, this assay has been used to assess the effects of carnitine palmitoyltransferase-2 and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-5 loss of function on fatty acid utilization9,17 and the impact of exogenous Wnt ligands and insulin18,19.

Normalization of the radioactive counts is critical to account for changes in cellular number that may result from gene manipulation, growth factor treatment, or the addition of pharmacological agents. The protocol calls for normalization to protein concentration as most laboratories maintain BCA assay kits or have other methods for quantifying protein. For protein normalization, it is vital to remove insoluble protein (collagens and other extracellular matrices) from the lysate before performing a BCA assay or further protein quantification. Without this step, results may be skewed by the abundance of extracellular matrix produced during osteoblast differentiation. Normalization to DNA content is also possible but would likely require the purchase of additional reagents. In either case, quantifying protein or DNA content in the cell culture flasks that have not been labeled with [1-14C]-oleic acid removes the precautions of working with radioactivity from this part of the assay. If the results for multiple experiments are to be combined, it is critical to calculate the total activity. This can account for any differences in the cpm measurements between the studies. In this regard, expressing data as a percent change in CO2 production or acid-soluble metabolite levels relative to the control treatment group is a convenient way to adjust for variability between experiments.

The use of oleic acid is described in this protocol due to its greater solubility, but 14C-labeled palmitate can also be utilized. As indicated above, radiolabeled fatty acids can also be replaced by 14C-glucose or 14C-glutamine. In this case, only the levels of 14CO2 are assessed. Similarly, primary calvarial osteoblasts can be replaced by cultures of marrow-derived osteoblasts, osteoblast-cell lines like Mc3t3-E1, or osteoclasts.

A limitation of this protocol, at least in our hands, is that assessing fatty acid oxidation in skeletal tissue explants has not been feasible (unpublished data). At this point, it is not clear if this is due to an inability of the labeled oleic acid to penetrate the calcified matrix and be taken up by a sufficient number of bone cells or some other problem. However, the protocol is suitable for use in tissue explants of soft tissue like adipose, liver, and muscle20,21. Additionally, the assay does not provide information on the step in the metabolic pathway where experimental treatments impact fatty acid catabolism. This type of analysis would require the use of more expensive 13C-metabolic flux experiments that can be rationalized based on the results of this assay.

Disclosures

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Merit Review Award from the Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service of the Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development (BX003724) and a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK099134).

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| [1-14C]-Oleic acid | Perkin Elmer | NEC317050UC | |

| 15 x 30 mm rubber sleeve stoppers | VWR | 89097-542 | |

| 1 mL syringe | BD precision | 309628 | |

| 25 G needle (25 G x 1 1/2 in) | BD precision | 305127 | |

| Ascorbic Acid | Sigma Aldrich | A4403 | |

| BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Fisher | 23225 | Other kits are also suitable |

| Beckman Scintillation Counter, or equivalent | Beckman Coulter | LS6000SC | |

| Beta-glycerol phosphate | Sigma Aldrich | G6626 | |

| Bovine Serum Albumin | Sigma Aldrich | 126609 | |

| Carnitine | Sigma Aldrich | C0283 | |

| Cellular lysis buffer | The protocol is amenable to typical lysis buffers (i.e. RIPA) | ||

| Dissecting forceps | Available from multiple sources | ||

| DNA quantification Kit | Available from multiple sources | ||

| Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline | Corning | 20-030-CV | |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | Available from multiple sources | ||

| Microcentrifuge tubes, 1.5 mL | Available from multiple sources | ||

| Minimum Essensial Medium, Alpha modification | Corning | 10-022-CV | |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | Gibco | 15140122 | |

| Perchloric Acid | Sigma Aldrich | 50439 | |

| Polypropylene center wells | VWR | 72760-048 | |

| Sodium hydroxide | Sigma Aldrich | S5881 | |

| T-25 canted neck tissue culture flask | Corning | 430639 | |

| Tissue Culture Incubator | |||

| Trypsin (0.25%)-EDTA | Gibco | 25200056 | |

| Ultima Gold (Scintillation solution) | PerkinElmer | 6013329 | |

| Whatman Chromatography paper | Sigma Aldrich | WHA3030917 |

References

- Cameron, D. A. The fine structure of osteoblasts in the metaphysis of the tibia of the young rat. Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology. 9, 583-595 (1961).

- Dudley, H. R., Spiro, D. The fine structure of bone cells. Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology. 11 (3), 627-649 (1961).

- Shapiro, I., Haselgrove, J. i. n., Hall, B. K. Ch. 5, Bone Metabolism and Mineralization. Bone Vol. 4. , 99-140 (1991).

- Komarova, S. V., Ataullakhanov, F. I., Globus, R. K. Bioenergetics and mitochondrial transmembrane potential during differentiation of cultured osteoblasts. American Journal of Physiology: Cell Physiology. 279 (4), 1220-1229 (2000).

- Bolton, J. G., Patel, S., Lacey, J. H., White, S. A prospective study of changes in bone turnover and bone density associated with regaining weight in women with anorexia nervosa. Osteoporosis International. 16 (12), 1955-1962 (2005).

- Nussbaum, M., Baird, D., Sonnenblick, M., Cowan, K., Shenker, I. R. Short stature in anorexia nervosa patients. Journal of Adolescent Health Care. 6 (6), 453-455 (1985).

- Alekos, N. S., Moorer, M. C., Riddle, R. C. Dual effects of lipid metabolism on osteoblast function. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 11, 578194 (2020).

- Karner, C. M., Long, F. Glucose metabolism in bone. Bone. 115, 2-7 (2018).

- Kim, S. P., et al. Fatty acid oxidation by the osteoblast is required for normal bone acquisition in a sex- and diet-dependent manner. JCI Insight. 2 (16), 92704 (2017).

- Niemeier, A., et al. Uptake of postprandial lipoproteins into bone in vivo: impact on osteoblast function. Bone. 43 (2), 230-237 (2008).

- Helderman, R. C., et al. Loss of function of lysosomal acid lipase (LAL) profoundly impacts osteoblastogenesis and increases fracture risk in humans. Bone. 148, 115946 (2021).

- Jonason, J. H., O'Keefe, R. J. Isolation and culture of neonatal mouse calvarial osteoblasts. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1130, 295-305 (2014).

- Haynie, K. R., Vandanmagsar, B., Wicks, S. E., Zhang, J., Mynatt, R. L. Inhibition of carnitine palymitoyltransferase1b induces cardiac hypertrophy and mortality in mice. Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism. 16 (8), 757-760 (2014).

- Long, C. P., Antoniewicz, M. R. High-resolution (13)C metabolic flux analysis. Nature Protocols. 14 (13), 2856-2877 (2019).

- Divakaruni, A. S., et al. Etomoxir inhibits macrophage polarization by disrupting CoA homeostasis. Cell Metabolism. 28 (3), 490-503 (2018).

- Raud, B., et al. Etomoxir actions on regulatory and memory T cells are independent of cpt1a-mediated fatty acid oxidation. Cell Metabolism. 28 (3), 504-515 (2018).

- Frey, J. L., et al. Wnt-Lrp5 signaling regulates fatty acid metabolism in the osteoblast. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 35 (11), 1979-1991 (2015).

- Frey, J. L., Kim, S. P., Li, Z., Wolfgang, M. J., Riddle, R. C. beta-catenin directs long-chain fatty acid catabolism in the osteoblasts of male mice. Endocrinology. 159 (1), 272-284 (2018).

- Li, Z., et al. Glucose transporter-4 facilitates insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in osteoblasts. Endocrinology. 157 (11), 4094-4103 (2016).

- Lee, J., et al. Loss of hepatic mitochondrial long-chain fatty acid oxidation confers resistance to diet-induced obesity and glucose intolerance. Cell Reports. 20 (3), 655-667 (2017).

- Kim, S. P., et al. Sclerostin influences body composition by regulating catabolic and anabolic metabolism in adipocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (52), 11238-11247 (2017).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved