Method Article

Transumbilical Endoscopic Resection of Intra-abdominal Mesenchymal Tumor

In This Article

Summary

The article introduces the surgical method, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for the complete removal of intra-abdominal tumors using natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). The procedure reaches the stomach by using gastrointestinal endoscopy, creating a controlled perforation for tumor removal, followed by stitching the gastric incision.

Abstract

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) typically occur in the stomach and proximal small intestine but can also be found in any other part of the digestive tract, including the abdominal cavity, albeit rarely. In the present case, the tumor was resected endoscopically through the anterior gastric wall. Computed tomography (CT) scan and gastroscopy of a 60-year-old woman revealed submucosal lesions in the gastric body. The possibility of a stromal tumor was considered more likely. The endoscopic surgery was performed under endotracheal anesthesia. After a solution had been injected at the lesion site in the stomach, the entire gastric wall was dissected to expose the tumor. As the lesion was in the abdominal cavity and its base was attached to the abdominal wall, it was accessed using a sterilized PCF colonoscope. A sodium chloride injection was administered at the base. The tumor was then peeled along its boundaries using the hooking and excision knife combined with the precutting knife. Subsequently, the tumor was pulled into the stomach through the incision made in the stomach and then extracted externally through the upper digestive tract using the ERCP spiral mesh basket. After confirming the absence of bleeding at the incision site, the endoscope was returned to the stomach, and the stomach opening was closed using purse-string sutures. The patient recovered satisfactorily following the surgery and was discharged on day 4. Histological examination revealed a low-risk stromal tumor (spindle cell type, <5 mitosis/50 high-power fields [HPF]). Immunohistochemistry revealed positive staining for CD34 and CD117, negative staining for SMA, positive staining for DOG1, and negative staining for S100. Additionally, the expression of ki67 was 3%.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) originate from the mesenchymal tissue of the gastrointestinal wall. GISTs contain pluripotent mesenchymal stem cells and exhibit the potential for malignant behavior. GISTs can manifest in various locations along the digestive tract, with the stomach being the most common site, and occasionally appear in the omentum, mesentery, and peritoneum. Histologically, GISTs contain spindle cells, epithelioid cells, and occasionally pleomorphic cells arranged in a bundle-like or diffuse pattern, reflecting their non-directional differentiation. GIST risk is stratified based on tumor size and nuclear mitotic count1.

Historically, surgical interventions for GISTs primarily comprised open surgery and laparoscopic procedures2. However, recent advancements in digestive endoscopic treatment techniques introduced the possibility of endoscopic resection for certain GISTs, either alone or combined with laparoscopy3. Digestive endoscopy uses the natural body orifices to minimize interference with the abdominal cavity, leading to quicker recovery compared to traditional or laparoscopic surgery. Furthermore, developing active perforation and endoscopic suturing techniques enables endoscopy to access the abdominal cavity and effectively remove intra-abdominal lesions following the principles of natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). Endoscopic resection of GISTs is based on endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and tunnel endoscopy techniques. Through endoscopic examination, gastrointestinal tumors or lesions can be precisely located within the digestive lumen. The endoscopic instruments are then used to accurately incise the mucosa, identify lesions located in the submucosal layer, intrinsic muscle layer, or even originating from the serosal layer, and completely remove them along the borders of the lesions. Due to the minimally invasive nature of endoscopy, there is minimal disturbance to the abdominal cavity. Compared to traditional surgery, endoscopic techniques not only ensure the complete removal of lesions but also maximize the preservation of the integrity and continuity of the digestive tract. Patients can resume early oral intake, experience quick recovery, and have significantly shortened hospital stays.4,5,6 With the development of endoscopic active perforation and endoscopic suturing techniques, endoscopy can penetrate into the abdominal cavity through natural orifices, explore and resect intra-abdominal lesions, achieving the effects of NOTES7,8.

As endoscopic treatment techniques continue to evolve, along with related instrument refinement and increased focus on screening, endoscopic submucosal resection is poised to become a mainstream approach for managing such lesions. This article reports a case of a rare intra-abdominal GIST adjacent to the stomach. Successful tumor resection was achieved using digestive endoscopic treatment techniques, showcasing the potential of endoscopy in this domain.

Protocol

This protocol follows the ethical principles of the Shantou Second People's Hospital and has obtained approval from the Hospital Ethics Committee, as well as informed consent from both patients and their families for this study and related videos.

1. Preoperative preparation and surgical approach planning for GIST resection

- Use the following inclusion criteria: The location of tumor growth has been confirmed through CT or gastroscopy examinations. The tumor is solitary, and its surface boundaries are clearly visible. Enhanced CT imaging indicates a relatively sparse presence of surrounding blood vessels. Gastroscopy reveals a clear projection of the tumor within the gastric cavity, with an estimated diameter of approximately 2 cm. It is anticipated that the tumor can be successfully removed through the upper digestive tract. Prior to the procedure, communication with the patient and family members took place, and their consent was obtained for the tumor excision surgery through endoscopy.

- Use the following exclusion criteria: For individuals with abnormal coagulation and cardiopulmonary function, unable to tolerate anesthesia; tumors that do not project clearly under gastroscopy; exceptionally large tumors expected to be inaccessible through the upper digestive tract; multiple lesions that cannot be completely excised via endoscopy; tumors surrounded by prominent blood vessels, anticipated to be unsuitable for endoscopic management.

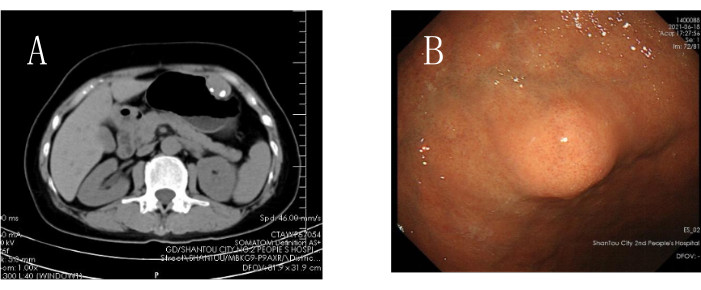

- In the specific case shown here, both the preoperative gastroscopy and CT scans unveiled the tumor position as anterior to the lesser curvature and within the middle section of the gastric corpus. Enhanced CT imaging exhibited the absence of substantial surrounding vasculature. Since optimal gastric distention does not affect the discernible localization of the tumor, select for a gastric wall incision at the tumor site for entry into the abdominal cavity for exploration and subsequent tumor excision (Figure 1A-B).

NOTE: This comprehensive preoperative evaluation and subsequent surgical strategy exemplify integrating advanced diagnostic techniques in tandem with precise anatomical insights to ensure optimal surgical outcomes in GIST resection procedures.

2. Aseptic preparation for GIST resection surgery

NOTE: Meticulous adherence to aseptic principles is paramount during such surgeries, given the presence of bacteria within the upper gastrointestinal tract juxtaposed with the sterile nature of the abdominal cavity. This condition necessitates stringent measures to maintain sterility.

- Sterile operating environment: Perform the surgical procedure in an aseptic operating room environment.

- Barrier techniques and instrument handling: Analogous to conventional surgical practices, for the operative site use sterile draping. Perform adequate disinfection of exposed operative areas. Unpack surgical instruments and place them on sterile surgical tables, adhering rigorously to aseptic requirements.

- Surgeons' attire and hygiene: Ensure all surgical personnel strictly adhere to surgical attire protocols. The protocols encompass thorough handwashing, donning surgical gowns, and wearing sterile gloves.

- Endoscope sterilization: For the endoscopes intended for treatment, perform rigorous sterilization. Ensure the requisite sterility by using peracetic acid to disinfect the endoscope and ethylene oxide gas to sterilize endoscope components.

- Instrument handling and exchange: Ensure that asepsis principles govern instrument exchange throughout the procedure. Ensure instruments entering and exiting the surgical field follow aseptic protocols and are placed on designated sterile surfaces post-exchange to prevent contamination.

NOTE: These stringent measures collectively safeguard against the risk of microbial contamination during GIST resection surgeries, enhancing patient safety and optimizing surgical outcomes.

3. Prophylactic antibiotic administration for preoperative care

- Provide the patient with prophylactic antibiotics before the surgery. Choose the antibiotics based on the types of potential pathogens in the upper gastrointestinal tract.

4. Instrumentation and equipment considerations

- Use the therapeutic gastroscope (see Table of Materials for details) for the procedure, accounting for instrument and equipment stability and reliability. Use the carbon dioxide insufflator to deliver medical-grade carbon dioxide for insufflation. For the lavage fluid, use 0.9% sodium chloride solution.

- Use the electrosurgical unit in parallel, and the precutting knife and hooking and excision knife for surgical maneuvers. Inject submucosal injection fluid consisting of 0.9% sodium chloride.

- Add 0.5 mL of methylene blue to the sodium chloride solution for chromoendoscopy. Using an endoscopic submucosal injection needle for submucosal injection, inject the solution consists of 0.9% sodium chloride solution plus 0.5 mL of methylene blue solution. The addition of methylene blue is intended to stain the submucosal layer after injection. The initial injection is approximately 3 mL, ensuring sufficient elevation of the mucosa.

NOTE: These meticulous equipment and technique choices emphasized the authors' commitment to precision and safety during GIST resection, enhancing procedural outcomes and patient well-being.

5. Operation procedure

- In line with standard protocols, conduct the surgical procedure using the following steps, which lasted a total of 2 h. Transport the patient safely to the operating room, where they receive endotracheal intubation for general anesthesia.

- After anesthesia is completed, place an oral bite block with an endoscope inserted to perform surgical disinfection on areas that may come into contact with surgical instruments, including the oral mucosa and skin. Place sterile drapes, exposing only the oral cavity. Surgical instruments and endoscopes strictly adhere to sterile principles as they are unsealed on the operating table.

- Initial gastric preparation: Initiate routine upper gastrointestinal examination by introducing the gastroscope orally, smoothly navigating into the gastric cavity. Lavage the gastric cavity using 0.9% sodium chloride solution until the fluid becomes clear. Aspirate the cavity thoroughly.

- Carbon dioxide insufflation: Gently insufflate the carbon dioxide gas into the gastric cavity, facilitating visualization of the tumor intragastric projection. Utilizing medical-grade carbon dioxide gas (purity ≥ 99.999%), introduce into the endoscope air and water supply connection section via a carbon dioxide pump. Gently inject carbon dioxide gas into the gastric cavity through the endoscope, facilitating a clearer observation of the tumor's projection within the stomach.

- Submucosal injection and tumor localization: Mark a suitable route for submucosal injection in the projected area of the tumor on the gastric wall. Incise the mucosal layer using the precutting knife, followed by gradual layer-by-layer dissection. Maintain hemostasis at the dissected edges, with particular attention on hemostasis during full-thickness gastric wall incision. Compress the gastric cavity progressively as carbon dioxide enters the abdominal cavity through the incision (Figure 2A-B).

- Endoscopic entry and tumor dissection: Insert the gastroscope in the abdominal cavity through the gastric incision and expose the tumor location. Perform submucosal injection at the tumor base and dissect using the combined precutting knife and hooking and excision knife along the tumor borders, ensuring detachment without harming the lesion. Inspect the submucosal layer carefully for branch vessels. Expose any identified vessels and coagulate using electrosurgical forceps to prevent hemorrhage (Figure 2C-E).

- Tumor retrieval: As the tumor dissection nears completion, confirm that only a minimal amount of submucosal tissue is connected the tumor to the base and this connection is devoid of vascular structures. Grasp the tumor and guide into the stomach using a spiral net basket. Remove the tumor orally (Figure 2F).

- Hemostasis and closure: Apply thorough hemostasis to the intra-abdominal wound, ensuring the absence of active bleeding. Retract the gastroscope into the gastric cavity and use nylon sutures or metallic clips endoscopically to perform purse-string sutures, securely closing the gastric incision site (Figure 2G-I).

- Closure and postoperative measures: Aspirate the gastric cavity following another round of carbon dioxide insufflation to confirm adequate gastric inflation and closure firmness and withdraw the gastroscope. Introduce a gastrointestinal decompression tube and conclude the surgical procedure.

NOTE: The systematic procedural phases reflect the meticulous attention to detail and adherence to advanced endoscopic techniques, underscoring the precision and thoroughness that characterize successful GIST resection surgery.

6. Postoperative care and follow-up

- Provide the patient with prophylactic antibiotics again following the surgical intervention. Monitor the patient's abdominal condition continuously. Remove gastric tube as a rectal passage of gas commences between postoperative day 2 and 3. Initiate a gradual transition from liquid to a regular diet based on the absence of discomfort post-tube removal.

- Sustained recovery and follow-up assessment: The patient's postoperative recovery was positive. Ongoing outpatient monitoring demonstrated the patient's normalization of health. Notably, no indications of tumor recurrence have been detected to date, affording optimism regarding sustained patient well-being.

NOTE: This comprehensive approach to postoperative care and continuous follow-up underscores our commitment to optimizing patient outcomes and ensuring the longevity of recovery following GIST resection surgery.

Results

With meticulous preoperative groundwork in place, digestive endoscopic treatment techniques and the innovative approach of controlled perforation have facilitated the feasibility of intraperitoneal GIST resection adjacent to the stomach. Notably, this surgical approach not only features rapid postoperative recovery but also capitalizes on the merits of NOTES.

The fusion of advanced endoscopic methodologies and innovative techniques has redefined the GIST resection landscape. This approach is characterized by its minimally invasive nature and capacity to harness the strengths of NOTES and underscores the authors' commitment to progressive and patient-centered surgical practices. Further refinement of endoscopic treatments is anticipated and will ultimately enhance patient outcomes and foster the evolution of minimally invasive surgical strategies. The surgical procedure proceeded smoothly, and the patient returned to the ward safely after the operation. The surgery lasted approximately 2 h, with minimal intraoperative bleeding, about 1 mL. The intraoperative fluid infusion volume was around 2000 mL, and no blood transfusion was required. To facilitate better healing of the gastric incision, a gastric tube was left in place after the surgery. The patient recovered well postoperatively, with continued prophylactic antibiotic use once. Abdominal conditions were monitored, and on the 2nd to 3rd day postoperatively, the patient began passing gas from the anus. The gastric tube was subsequently removed, and the patient experienced no discomfort after removal, allowing a gradual transition from a liquid to a regular diet. The patient was discharged on the 5th day postoperatively (Table 1). Pathological results indicated a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (size: 3.5 cm x 3.0 cm x 2.5 cm), characterized as spindle cell type, with fewer than 5 mitotic figures per high-power field, considered low risk. Immunohistochemistry revealed positive staining for CD34 and CD117, negative staining for SMA, positive staining for DOG1, and negative staining for S100. Additionally, the expression of ki67 was 3%.

Figure 1: Preoperative radiological examinations. (A) Preoperative CT examination. (B) Preoperative gastroscopy examination. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Surgical Procedure. (A) Administration of appropriate submucosal injection. (B) Stepwise incision of the gastric wall. (C) Exploring the tumor's intra-abdominal location to gain insight into the lesion. (D) Injecting at the tumor base, separating the tumor from its base, ensuring smooth entry to the correct dissection plane. (E) Gently dissecting along the border using an endoscopic cutting tool. (F) Capturing the tumor using a retrieval basket and removing it orally through the gastric incision. (G) Confirmed complete tumor removal and no active bleeding at the surgical site. (H) Suturing the gastric incision using an endoscopic suturing technique. (I) Completely excised tumor extracted through the oral cavity. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| Items | Results |

| Operation time (min) | 120 |

| Surgical blood loss (mL) | 1 |

| Surgical fluid infusion volume (mL) | 2000 |

| Placement of what type of drainage tube | Gastric tube |

| Postop complications | None |

| Discharge time | The 6th postoperative day |

Table 1: The data from various aspects related to this surgical case.

| Laparoscope | Gastrointestinal Endoscope | |||

| Rigid/Flexible | Rigid | Flexible | ||

| field of view | relatively wide, with distant, intermediate, and close-up fields of view | Narrow field of view, unable to operate at a distance | ||

| move | active movement | passive movement | ||

| target localization | Target localization is not easily lost | Prone to getting lost easily due to influence | ||

| Instrument insertion and removal method | Multiple puncture sites can be punctured as needed | Only one or two channels/clamps | ||

| surgical instruments | Abundant instruments, large operating range | The instruments are relatively limited and the operating range is small | ||

| suction device | independent suction device | Sharing the same suction channel with instruments, prone to interference | ||

| surgical technique | Can be assisted by assistants, using multiple puncture sites for the entry and exit of various instruments to assist in surgery | Without assistant support, relying on gravity or other special means to expose blind spots | ||

Table 2: The difference between laparoscopy and gastrointestinal endoscopy for surgery.

Discussion

Despite the demonstrated efficacy of targeted agents such as imatinib for treating GISTs1,2, surgical resection remains the primary therapeutic approach for primary GISTs2,9. Recent advancements in endoscopic diagnostic and therapeutic techniques combined with the evolution of NOTES principles have generated a spectrum of intracavitary endoscopic surgical techniques7,8. These techniques include endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal tumor excavation via tunneling, and endoscopic full-thickness resection of the gastrointestinal tract. Such modalities render it feasible to achieve complete excision of submucosal lesions within the esophagus, stomach, and even the colon, including entities such as GISTs and leiomyomas. Furthermore, these approaches yield a maximized minimally invasive effect while preserving the structural integrity of the gastrointestinal tract.

While the minimally invasive nature of NOTES has gained widespread recognition, it is important to acknowledge the substantial structural and instrumental disparities between gastrointestinal endoscopy and laparoscopy (Table 2). Employing endoscopy for surgical interventions still presents a relatively higher level of procedural complexity than laparoscopic procedures, particularly in regions such as the abdominal cavity, where the spatial volume significantly exceeds that of the gastrointestinal lumen. Consequently, meticulous preoperative preparation is pivotal for successful endoscopic operations. The present case showcased the surgical technique. Primarily, the tumor was on the anterior stomach wall. This location was both the intragastric projection of the tumor and where the stomach endoscope was more likely to perforate the gastric wall, minimizing the risk of being off target. Therefore, the authors used this position as the site of deliberate perforation, traversing the gastric wall to locate the tumor. Subsequently, the tumor boundaries were meticulously dissected using endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) techniques.

When only a minute amount of submucosal attachment remained following nearly complete tumor dissection, the authors ensured that the area connected to the tumor was devoid of blood vessels to avert difficulties locating the tumor following complete excision and its potential intracavitary dislodgement. Subsequently, the tumor was entrapped using a helical net basket, pulled through the gastric incision into the stomach, and retrieved from the upper gastrointestinal tract. Following these steps, hemostasis procedures were performed on the incision site. The gastric incision was closed using endoscopic purse-string suturing. A gastric decompression tube was retained to facilitate optimal and rapid incision healing. This measure was taken to prevent gastric distention, and gastric fluids were aspirated to reduce their corrosive impact on the incision site. This sequence of measures collectively enhanced patient recovery. Reviewing the entire process of this surgical case, the success of the procedure can be attributed to several key factors. Firstly, precise localization was achieved by using a gastroscope to accurately identify the tumor's position within the stomach, designating it as the active perforation site to prevent disorientation within the abdominal cavity. Secondly, the proficient use of various endoscopic surgical instruments played a crucial role. Given the limitations of a single endoscopic channel, understanding the characteristics of instruments, such as the hooking and excision knife and precutting knife, was essential for successful tumor dissection. Different instruments were strategically combined to achieve complete tumor removal. Additionally, preoperative and intraoperative assessments focused on determining whether the tumor size allowed for complete extraction through natural cavities, considering the emphasis on tumor integrity in this surgery. Lastly, proficiency in special endoscopic suturing techniques was necessary for the smooth closure of the gastric incision under endoscopy.

However, challenges in this case included ensuring the integrity of the tumor capsule. While preserving the capsule is comparatively easier in laparoscopic or open surgery, the lack of tactile feedback and limited vision in endoscopic procedures, along with the absence of an assisting hand, increased the difficulty in maintaining the capsule's integrity. This necessitated the operator to be proficient in endoscopic surgical techniques and possess experience in endoscopic procedures. Another challenge involved the difficulty in locating the tumor due to the limited endoscopic field of view. To address this, a strategic approach was implemented, involving careful confirmation of the attachment site and the use of a helical net basket to retrieve the tumor through the gastric incision and extract it through the upper digestive tract.

Using gastrointestinal endoscopy for tumor resection has been substantiated as a secure and efficacious approach for GISTs measuring <2 cm in diameter2. GISTs > 5 cm diameter present intermediate or high risk of recurrence; therefore, surgical excision (via open or laparoscopic methods) remains the preferred therapeutic strategy. Robust evidence-based support for the optimal treatment approach for GISTs within the 2-5 cm range is currently lacking10,11,12. A 12-year single-center study conducted at Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, China, indicated that endoscopic surgery might be a suitable option for such GISTs11. The findings suggested that the safety and effectiveness of endoscopic resection performed by experienced endoscopists appear comparable to that of conventional surgical excision13. Intriguingly, the endoscopic resection group exhibited shorter surgical durations and reduced postoperative hospital stays10,14.

In summary, applying endoscopy for intra-abdominal gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) resection is a safe and effective NOTES surgical approach. However, this procedure also comes with its limitations, requiring operators to possess advanced skills in handling complex endoscopic surgeries. There are restrictions regarding tumor size, and for larger tumors, an inability to be completely extracted through the digestive tract is considered a contraindication for this surgery. During the operative process, it is crucial to ensure the integrity of the tumor capsule, preventing capsule damage that could lead to the dissemination and metastasis of the tumor.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgements

None.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Disposable Endoscope Injection Needle | Boston Scientific Corporation | ||

| Dual knife | Olympus | KD-650L | |

| Endoscopic Ligation Device (Nylon Suture) | Leao Company | ||

| IT2 knife | Olympus | KD-611L | |

| Olympus 290 Host System | Olympus | ||

| Olympus Endoscope Dedicated Insufflator | Olympus | ||

| Olympus Endoscope Dedicated Water Pump | Olympus | ||

| Olympus Therapeutic Gastroscope GIF-Q260J | Olympus | GIF-Q260J | |

| Rotatable Reusable Endoscope Metal Clip | Nanjing Micro-Invasive Medical Co., Ltd |

References

- Kollár, A., Aguiar, P. N., Forones, N. M., De Mello, R. A. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): Diagnosis and treatment. Int Manual Oncol Pract. 2, 817-849 (2019).

- Li, J., et al. Chinese consensus guidelines for diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Chinese J Cancer Res. 29 (4), 281 (2017).

- Digestive Endoscopy Tunnel Technical Cooperation Group of Digestive Endoscopy Branch of Chinese Medical Association, E.P.B.o.C.M.D.A., & Association, D.E.B.o.B.M. Expert consensus of endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal stomal tumors in China (2020, Beijing). Chin J Gastrointest Endosc. 7, 176-185 (2020).

- Liu, Z., et al. Comparison among endoscopic, laparoscopic, and open resection for relatively small gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors (< 5 cm): a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 11, 672364 (2021).

- Wang, C., et al. Safety and efficiency of endoscopic resection versus laparoscopic resection in gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumours: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 46 (4), 667-674 (2020).

- Wu, J., et al. Comparative study on the clinical effects of different surgical methods in the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022, 1280756 (2022).

- Chen, L. Advancements in digestive endoscopic resection: From mucosa to serosa. J Third Mil Med Univ. 19, 5 (2019).

- Wang, D., Li, J. New developments and innovations in NOTES. Chin J Digest Endosc. 35 (9), 609 (2018).

- Koo, D. H., et al. Asian consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Res Treat. 48 (4), 1155-1166 (2016).

- Joo, M. K., et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of endoscopic treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. Gut and Liver. 17 (2), 217 (2023).

- Lei, T., et al. Endoscopic or surgical resection for patients with 2-5cm gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a single-center 12-year experience from China. Cancer Manag Res. 12, 7659-7670 (2020).

- Colombo, M., Spadaccini, M., Maselli, R. Endoscopic resection of GIST: feasible or fairytale. Laparosc Surg. 6, 12 (2022).

- Yin, L., et al. Comparable long-term survival of patients with colorectal or gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors treated with endoscopic vs. surgical resection. Surg Endosc. 36 (6), 4215-4225 (2022).

- Yoo, I. K., Cho, J. Y. Endoscopic treatment for gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Clin Endosc. 53 (4), 383-384 (2020).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionExplore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved